Ian McKee : We are GLM

London's Garden Bridge: Sculpture or Functioning Form?

February 11th, 2015

GLM architect Neil McAlllister was asked to weigh in on London’s controversial Garden Bridge - when is it okay for architectural design to exist merely as a spectacle and not to be used by the masses? Neil?

When considering the proposed Garden Bridge, the first thing to recognise is that primarily it is not a bridge. If there was a need for another pedestrian crossing of the Thames at this point, a need which is disputed by many, a high quality bridge could have been commissioned at a fraction of the cost. The Millenium bridge, further along the river, cost a mere £18m and even Calatrava’s beautifully sculptural Puente del Alamillo in Seville is estimated to have ‘only’ cost around $40m compared to the eye-watering budget of £175m for this project. Instead I would suggest this is primarily a sculpture – a piece of public art – one that can be walked on but ultimately it is designed as a piece of fantasy not as a means of transportation. It is clear that the originators of the scheme had no greater practical purpose in mind as they want it to be “the slowest way to cross the river”.

Architects have always dreamt of fantastical structures. Some of these have grand theories behind them, like Paolo Soleri’s arcologies; some are monuments to great events or great men, like Boullée’s monument to Isaac Newton; others are solely creations of geometric gymnastics and whimsy; but most of them are never built and only live in the minds of their creators or in their drawings and models.

As a fantasy, this one is quite interesting – the form is elegant, the mushroom forms organic, and the idea of trees growing out of a bridge spanning over a river is an intriguing image, reminiscent of the floating “Hallelujah Mountains” in the sci-fi film “Avatar”. Apparently the inspiration came from Joanna Lumley’s memories of a childhood in Kuala Lumpur with gardens apparently floating on the mist and a desire to create a “floating paradise garden”. This is an image that I can imagine dreaming of, sketching, modelling, painting but is actually building it justified?

The question revolves not around the building of this fantasy but the building of it in a very public place, with limited public access with significant amounts of public money. Once this is built in the centre of London it will no longer be just the dream of a few people but the concrete reality of the many – radically changing the appearance of the city where they live, work or visit. Although it will constantly be visible to the public, access will be restricted. This is not unusual for monuments, or even conventional land-based parks where gates are frequently closed at night. However, some of the suggested restrictions – like limiting the size of groups using it without prior notice to eight – make it clear that this will only be a pseudo-public space.

As a fantastic monument to nothing with controlled public access, the final question is, if we want this modern day folly built in the first place, should it be funded with £60m of public money? Obviously this is a tiny part of the government budget – a mere drop in the ocean compared with Crossrail or HS2 – but if that money is available to spend on infrastructure, creation of public spaces and regeneration of inner city areas could it not be more effectively spent elsewhere? Several elegant bridges and beautiful public spaces along the embankment could be created – but would that have the same fanciful appeal?

Neil joined GLM in 2008 where he took a leading role in the regeneration of the Inn at John O’Groats. In addition to conservation work, Neil has worked on various domestic and commercial projects ranging from estate cottages to high-end private houses and from cafés to hotels.

Will LBTT Kill the Property Market in Scotland?

January 30th, 2015By David Gibbon - Director, GLM

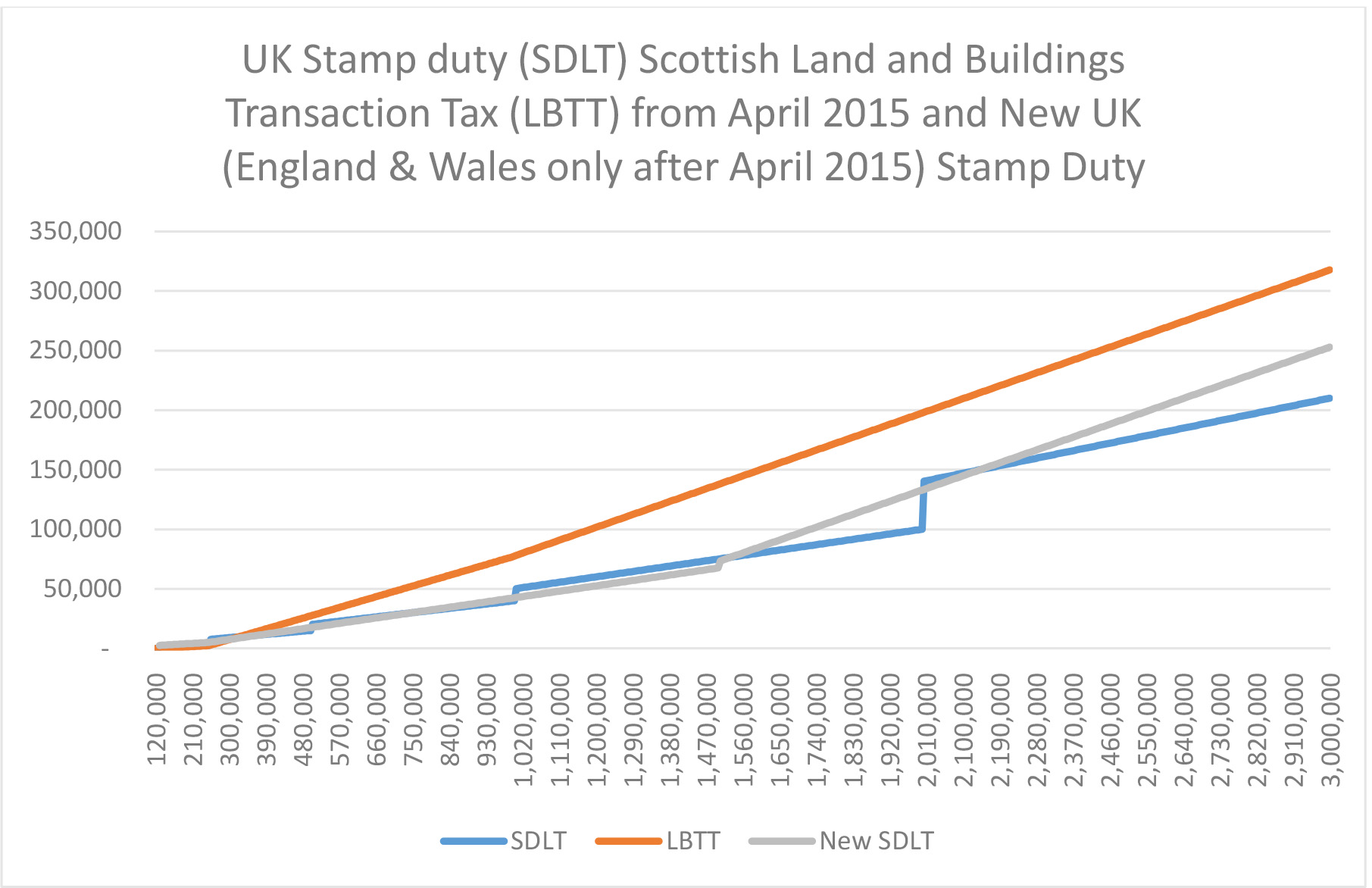

The differences between English and Scottish property, already distinctive because of the differing legal systems and property purchase systems, are destined to move further apart. The new transaction tax due to commence in Scotland in April or whenever a new computer system and a new organisation can be put in place, will make the cost of property transactions distinctly more expensive in Scotland than in England with the marginal exception of the sort of properties that buy-to-let landlords favour, which will be cheaper. The UK Stamp Duty (applicable in Scotland until April) has also been revised but much less dramatically. When SBTT comes into force, for much of the market a property in Scotland will cost significantly more in tax than the equivalent property in England. Of course in practical terms this will not be so noticeable when making comparisons because property in Scotland is so much better value than property in England, or at least in the South East but it will make a difference to the market within Scotland.

At the height of the property boom it was always something of a puzzle that UK governments did not use the mechanism of Stamp Duty to dampen down the property market when the market got over heated. Conversely it seems odd that the Scottish Government have decided to put the brakes on property during a period of poor economic activity. On the face of it, by following Scotland’s lead in ironing out the manifestly market distorting steps in the level of Stamp Duty tax but making hardly any change to the overall tax level, the UK government has played a better hand.

Scotland’s LBTT may, politically, play as a sort of Mansion Tax without all the obvious drawbacks of such a tax. If it slows the transaction market that might be seen as a good thing, making property speculation and, in particular, property development, less attractive. However there are likely to be negative effects. Niche developers have done much to lessen the impact of the housing shortage by adapting the existing housing stock to changing needs. However if a larger slice of their profit on every transaction is taken by the government, niche development will become harder. If there is less movement in the market and people stay longer where they are, this could also lead to less efficient overall utilisation of the housing stock as well as less activity devoted to adapting it: a sort of “bedroom tax” in reverse for the private sector?

Another concern could be in the large country house market. Scotland is well endowed with some remarkable properties, many of them the product of inward investment and returning Scottish expats who made their fortunes in the further reaches of the Empire. These properties could be seen as an asset to Scotland but, in many cases, are a liability to their owners. Although they take wealth to own and maintain, they usually make very little economic sense so they attract owners, including present day ex-pats amongst others, who are drawn by considerations other than, purely, money. In view of the considerable scale of this legacy it could be argued that we need to nurture rather than to repel this type of investor. Imposing a further tax on them could land the country with a great many formerly magnificent but now deteriorating mansions.

However if Scotland wishes to dampen down the property market and, perhaps, drive innovation and investment to seek other avenues of fulfilment, perhaps the new LBTT will ultimately be seen as a benefit but in overall terms this looks like a risky strategy and it does not look like an especially deft move.

Making Your Existing Building Work Better

January 9th, 2015I’m the Managing Director of GLM, a multi-disciplinary practice of building surveyors, architects and project managers and we’re in the business of solving problems.

I’m often asked what a building surveyor does and how our service is enhanced by joining forces with architects. As a chartered building surveyor myself, I often start off by explaining that I’m essentially a building doctor.

Sometimes I’m the GP looking at the general health of a building, diagnosing problems, reporting them to the owner or prospective purchaser and prescribing a course of action to set things right again.

Sometimes intervention is required and I’m the surgeon, opening it up, repairing and upgrading its vital services or rejuvenating it by giving it a facelift.

And very often, I’m the pathologist carefully examining, inquiring and testing to discover the mechanism of failure, to learn lessons and to feedback into our design processes.

Our building surveyors fix your building and our architects respond to your aspirations, giving form and meaning to your space. Under the watchful eye of our conservation accredited director, David Gibbon (one of the very few practising conservation accredited building surveyors in Scotland) we are well placed to take on old, unusual or problematic buildings. Finding new uses for existing buildings is our bread and butter.

But just because we excel in the old doesn’t mean we can’t embrace the new. At GLM, it’s all about balance. When we see an unused, dilapidated and unloved building, our first instinct isn’t to knock it down and rebuild, we believe the greenest building is the building you already have, but how can we make it better?

We recently completed the regeneration of John O’Groats which included a £2.5 million extension and refurbishment of the long abandoned John O’Groats House Hotel, left to rot for years. Although it would have been unquestionably cheaper to flatten the site and start again, the existing building was clearly an iconic part of the location.

Our project architect Neil McAllister designed a distinctive extension that expresses the area’s Nordic heritage. This welcome splash of colour in a sometimes bleak landscape signals to the world that something new has emerged from the dereliction. By putting our heads together, GLM’s building surveyors, architects and project managers managed to reverse the decline of a beloved tourist destination, save an iconic Scottish building and provide the country with a new, colourful landmark.

I am thrilled to be a contributing blogger for Urban Realm. Expect to hear not just from me, but from the entire GLM team as we bring you interesting news and thoughts on our ongoing projects throughout the UK and on industry news and developments.