Mimesis, Manifesto of Memory: Cultural Formation

5 Aug 2025

Roger Emmerson looks at the rise and demise of architecture as a tool of cultural formation, addressing how a simplistic return to local forms on neo-vernacular grounds, despite some superficial appeal, is destined to fail as it carries too many messages at one time.

One of architecture’s several purposes, less frequently acknowledged today, is in cultural formation. In pre- Renaissance European and Near Eastern societies this was inherent and evolutionary, essentially mimetic, not self-conscious or revolutionary since there were no religious, philosophical, material or practical alternatives to what had originated in folk tradition. As Vitruvius said, such building was simply what the Gauls, Colchians, Phrygians and others variously did of necessity (Vitruvius 2009, 38). He went on to say: Besides, when they had daily become more manually adept at building and had, by cleverly exercising their ingenuity, arrived at a mastery of these arts, then the habit of hard work instilled in their minds also enabled those pursuing the practices most assiduously to proclaim themselves craftsmen.

So when these arts had been developed like this at the beginning, and nature had not only enriched human beings with senses like other living beings, but had also reinforced their intellectual capacities with powers of reasoning and common sense and had subjected other animals to their power, then men, progressing gradually from the construction of buildings to other arts and disciplines, moved themselves on from their wild, rustic lives to gentle civilization (Vitruvius 2009, 39).

Vitruvius established his own objectives within the more sophisticated although equally inhering cultural context of the Roman Empire: Therefore, since I was indebted to you – Caesar Augustus – for this favour, which was such that I need have no financial anxieties for the rest of my life, I began to write this work for you since I noticed that you have built and continue to do so now, and that for the foreseeable future you will ensure that both public and private buildings will so match the majesty of your achievements that they will be handed down in the memory of future generations (Vitruvius 2009, 4).

Albeit that such works were based on the Romans’ cultural appropriation and subsequent development of Greek and Tuscan models. He was right about memory. Conscious cultural formation is an attribute of the Renaissance. Palladio discussed several different cultural traditions in house-planning – the Tuscan, the Corinthian,the Egyptian, the Rhodian, the Roman – and advocated their contemporary applicability (Palladio 1965, 42-5). It is also an attribute of nineteenth-century Gothic in that John Ruskin promoted its virtues in contrast to the vices of the Renaissance as he saw them for “Now Venice, as she was once the most religious, was in her fall the most corrupt, of European states; and as she was in her strength the centre of the pure currents of Christian architecture, so she is in her decline the source of the Renaissance” (Ruskin 1907, 23).

Or of the Modern Movement where, among a hundred other twentiethcentury manifestos, Le Corbusier rejected Ruskin, in turn, since “Gothic architecture is not, fundamentally, based on spheres cones and cylinders… It is for that reason that a cathedral is not very beautiful and that we search in it for compensations of a subjective kind outside plastic art” (Corbusier 1963, 32). Le Corbusier, even in his ahistorical and anti-aesthetic prime, recognised the significance of the subjective. Or, closer to our own time, there is the conscious cultural and social transformation attempted by the physical and administrative architecture of the Welfare State (Ravetz 1974) (Curtis 1984). Of course, all these instances of conscious cultural formation, as Vitruvius recognised, are the doings of potentates whether Roman Caesars; Renaissance Princes; Popes, Archbishops and Moderators; Kings and Emperors; Dictators and totalitarian states; corporate private and public bureaucracies; land-owners and the conspicuously wealthy: the few. Our concerns today are for the many – the working class, women, people of colour, people of diverse gender, the poor, the immigrant, the stranger – not represented in that conventional cultural history having their own diverse cultural histories and needing appropriate means of expression. That a “history written by the victors is not the only history” (Kynaston 2024, 567), or rather not one written by those who presume to winner status. A case in point is the continuing furore surrounding the proposed sculpture of the pioneer in women’s healthcare, Elsie Inglis with unanswered questions about appropriateness of model, message and maker (Brown 2022). Conscious cultural formation, then, almost invariably has an agenda.

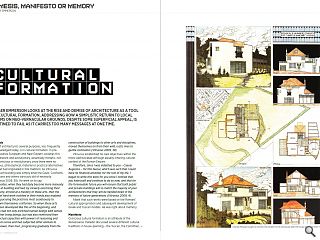

In UK architecture, from time-to-time, that agenda has been contradictorily a search for a “new vernacular” (Essex 1973)(Lyall 1980, 70)(Walker 1991, 58) (Wilson 2017, 163-4) A variant of that agenda in Scotland 49 has been the desire to excavate a formative place for a Scottish vernacular within a conventional history of the Modern Movement. The objective is twofold: on the one hand, to confirm the visual appropriateness of the incoming architecture to the context of a Scottish vernacular and, on the other hand, to assert the prime architectural genesis and authority of a Scottish vernacular in the formation of that Modernist aesthetic. This has been expressed, more in retrospective commentary on completed works rather than through initiating design theory, by John Summerson, Mansfield Forbes, William Dey, Robert Hurd and others in the 1930s and more recently and less authoritatively by Charles McKean (McKean 1987 and 1991) and Frank Walker (Walker 1985, 1991 and 2023) and not with any great success at any time. While I am not supportive of the conscious creation or recreation of a vernacular (Glenday 2023, 32-7), I should confess to my part in a process of an attempt to recover, transform and reuse recognisable Scottish formal motives. In 1987, I was commissioned by Mactaggart & Mickel to design the pavilion they were to share with the Scottish Milk Marketing Board at the 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival. This was based on an unbuilt Mack & Mick house from 1935 (McKean 1988a, 36-37).

I was intrigued by the 1930s aesthetic and followed up the pavilion with two speculative house designs (McKean 1988b, 39) which sought to marry a modernist style to an essentially Arts & Crafts house plan. The late Charles McKean – then Secretary and Treasurer of the RIAS, subsequently Professor of Architecture at the University of Edinburgh and later Professor of Scottish History at Dundee University – whom I knew well and had corresponded with since 1984, was intrigued by these designs and, together with his wife Margaret, commissioned from me in 1989 a substantial extension to their late 1930s-designed, early 1950s-built house in Hill Park, Edinburgh. In his book The Scottish Thirties McKean had attempted to show through built examples the presence of the twofold vernacular/modern connection but was obliged to concede that: “Trying to define Thirties architecture is like chasing a chimera: the closer you get the further out of reach it seems” (McKean 1987, 43). The book was a toned-down version of his privatelyexpressed hopes in this matter. Following criticism by Professors Andy MacMillan and Isi Metzstein of his thesis, McKean, to provide the intellectual heft missing from the book, retrospectively posited Scotland’s 1930s architecture within a North European context (McKean 1991, 88-95) although Pevsner had said as much in 1936 (Pevsner 1966, 171). As a historian not a designer, McKean had no means of demonstrating the plausibility of his notion beyond his speculation on the buildings and texts referred to in his writings and, in effect, intended the house extension to become, by proxy, the three-dimensional manifesto of his thesis. The design, to McKean’s antisyzygistic brief to “make it Scottish, thirties, contemporary, a tower” – Mrs McKean wished it to be “practical” – was illustrated in the Spring 1990 issue of Prospect (Prospect 1990, 26) and exhibited together with a model at the 1991 Royal Scottish Academy Summer Exhibition (Jaques 1991, 12) (RSA 1991, 19 and 21) by which time the works were underway on site. The existing house presented a dull east-facing elevation and garage to a significant corner on rising ground within the Hill Park estate as it would up the northeast slope of Corstorphine Hill with distant views of the city centre only visible from the stair.

The garage was consequently relocated to the western elevation, cut into the bank, freeing up the reorientation of the extension – containing new living room and master bedroom with en suite – towards the large garden and views eastwards towards the city centre and Edinburgh Castle while offering a more significant architectural presence to the street. The new elevation was shown as a curving screen, the curve used as a means of optically increasing the 51 wall’s apparent height and bulk, enhanced by the oversized lintel over the first floor window. This became almost a curtain wall in its original meaning, screening the new accommodation, and was visually separated from the existing house at the south by means of two storey glazing and a balcony allowing southwest light to penetrate the east-facing rooms. Also at the south end the wall was projected in a small jettied fin which carried, in mosaic, a Scottish Bluebell or Harebell motif, with its several propitious symbolic meanings of humility, gratitude and constancy, stylised much as it might have been in the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

At the north end the screen was likewise projected to hide the pitched roof formed to allow daylight into the new dormer window at the head of the reconfigured stair. McKean’s antinomial verdict (McKean 1992, 161) on completion was that the extension represented a “curved Scots cubism” which might mean that it ably satisfied his objectives. A design for an individual client did not easily translate to a wider market, a market occupied by volume house-builders. A chance meeting with Charles Wemyss of The Wemyss Brick Company led to the discovery of his interest in producing what he termed “the Scottish brick house” and his challenge to me to design such a thing. The main issue, of course, was what was then perceived as the incompatibility of the use of brick within the Scottish building tradition. Within the context of recognisable Scottish built form detail was introduced from the German and especially Netherlandish use of brick in a group of five house types(Coutts 1990) (McDonald 1991, 18-19). In the end, volume house-builders while intrigued were unconvinced and Wemyss himself expressed doubt (Glendinning et al. 1993, 497).

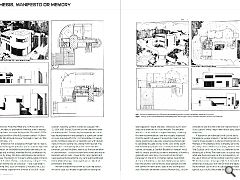

Fast forward to 2004 and the designs for a luxury residential development of flats and houses at Elmfield Road in the heart of the Gosforth Conservation Area, Newcastle upon Tyne for Miller Northern. The conservation area comprises of detached, semidetached and terraced brick-built houses from between 1880 and 1910 in that loose confection of the Aesthetic, Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau often known as English Free Style. I spent some considerable time walking the streets of Gosforth sketching, photographing and taking notes of what I saw with the intent of incorporating such forms and details, compatible with contemporary site practice, in the designs. I won’t go into the protracted planning process, suffice to say by mid-2006 planning permission and conservation area consent were achieved and the works commenced.

I returned to Edinburgh shortly after, making only brief return forays to Newcastle to play the infrequent gig. On one such occasion in 2008, I was invited to perform at the newly reopened, refurbished and extended Tyneside Cinema, Pilgrim Street, a small Art Deco masterpiece (Rae 2008)(McCombie 2010, 142). In the bar prior to playing, I was accosted by the planning officer from Newcastle City Council with whom I’d negotiated the permissions. There was mutual surprise: he, that I was one of the acts; me, that he was present at the gig. In the course of a friendly conversation he said to me, “you remember the Elmfield development? They’re known locally as the ‘Scottish Flats’.” Was this a “memory” of mine so egregious it was unmistakeable? There was no great chance that the locals would have known I was Scottish; I worked with a Newcastle practice. Perhaps, all that exploration in the 1990s had proved a far stronger influence than the many sketches of English Free-Style details I had made prior to designing the Elmfield development. Judge for yourselves.

|

|