Three Bridges: Deeside Divide

5 Aug 2025

The opening of Moxon’s new bridge at Gairnshiel on Deeside prompts Mark Chalmers to investigate the wider role of infrastructure in tying Deeside together. Amidst concern that two bridges further downstream at Aboyne and Dinnet are reaching the end of their design lives, are communities in danger of being cut off?

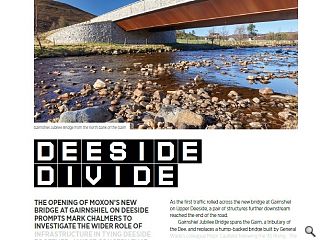

As the first traffic rolled across the new bridge at Gairnshiel on Upper Deeside, a pair of structures further downstream reached the end of the road. Gairnshiel Jubilee Bridge spans the Gairn, a tributary of the Dee, and replaces a hump-backed bridge built by General Wade’s colleague Major Caulfeild following the ‘45 Rising.

The new crossing was designed by Moxon Architects, working with the engineers Arcadis, and consists of paired Cor-Ten steel girders which carry the deck, while the parapets are clad in granite rubble. The new bridge blends the contemporary with the contextual, and it has won several design awards since opening in 2023 – including a newly-announced RIAS Award for 2025. Downstream of the Gairn’s confluence with the Dee, there are larger bridges every few miles which link the main North Deeside Road to the southern side of the river. The bridge at Dinnet carries timber lorries to one of Scotland’s biggest sawmills at Burnroot, while the bridge at Aboyne links the parishes of Finzean and Birse to one of the main settlements on Deeside.

They’re vital connections which stitch the outlying communities together. But Aboyne Bridge is closed. It needs up to £3mn of remedial work: the hinge at the centre of its main span is suspect, and the bridge deck has reached the end of its life. Repairs are a high priority for Aberdeenshire Council, and the bridge’s condition has climbed to “black alert”. It closed to traffic at the end of 2023, and isn’t expected to reopen until remedial work is complete in 2026 or 2027. Even then, it will have a permanent 18 ton weight restriction. Around the same time that Aboyne shut, restrictions were also placed on Dinnet Bridge.

Dinnet lies five miles upstream and is coded red, the next highest alert. It needs an estimated £4mn of work. In the meantime, traffic was reduced to a single lane for a spell, in order to protect its integrity. It’s unfortunate that both bridges reached this point at exactly the same time: the diversion via Potarch Bridge adds half an hour to the journey from Aboyne to Birse. Deeside’s bridge predicament adds one more concern to add to the cost of living crisis, housing emergency and climate crisis. You could view the current state of transport infrastructure in Scotland, the UK, and Europe in general, as a Malcolm Tucker-style omnishambles or polycrisis – but look beyond the headlines, and rural connectivity is a more nuanced issue. In the early 1930’s, Aberdeenshire County Council, the predecessor of the current authority, decided to improve the river crossings on upper Deeside.

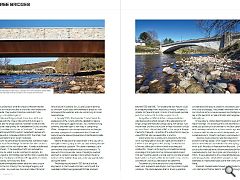

As a forward-looking authority, they were open to new ways of doing things. While civil engineers are innately conservative and bridges are rarely a playground for experimentation, Dinnet and Aboyne became pioneering examples of reinforced concrete construction. Aboyne Bridge sits on an open stretch of the Dee, with a flood plain stretching away to the south and a heavily-wooded shingle island just upstream. The island is nameless, but in summertime it lies tantalisingly close to the riverbank. To cope with the Dee’s periodic spates, the bridge’s southern approach is carried on a series of flood arches: the stony vastness of the shallows disappears under raging white water during the winter. The bridge was designed in 1937 by the structural engineers F. A. MacDonald & Partners, working with the Aberdeen architect George Bennett Mitchell, and built between 1938 and 1940. To the untrained eye, Aboyne could be a masonry bridge from the previous century.

In reality, its graceful 52 metre main span consists of a reinforced concrete portal frame dressed to look like a segmental arch. George Bennett Mitchell & Son is a long-established Aberdeen practice which worked on the redevelopment of Kings College and Marischal College, along with various Trust House hotels plus the construction of Royal Insurance’s offices on Union Street. Mitchell died in 1941, so the bridge at Aboyne may be his final work – or perhaps the work of his son, George Angus Mitchell, who succeeded him in practice.

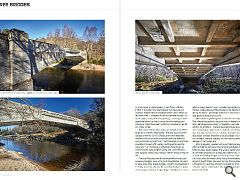

Dinnet Bridge lies in a rocky cleft, closed in by the trees which overhang salmon pools and rapids on this stretch of the Dee. It was designed in 1935, also by F. A. MacDonald & Partners, although this time without an architectural collaborator. Dinnet is a thoroughly unconventional design, consisting of triangular concrete cantilevers which project from each bank to support a central span of concrete-encased beams and cross-beams, while the abutments consist of mass concrete piers which counterbalance the cantilevers. Fundamentally, there are only four types of bridge – beam, arch, suspension and stayed – but they come in myriad variations. The choice between them is driven by practical considerations like ground conditions, flood levels, land take, wind loads and budget. MacDonald’s innovation with material and structural form is unusual, because most bridge concepts rely on the heuristics, or rules of thumb, which engineers habitually use.

Unlike Aboyne, Dinnet doesn’t pretend to be an arched masonry bridge. The detailing of the piers resembles coursed ashlar, but up close you can see that it’s Art Deco concrete work, and very much of its time. In our current age, which is obsessed with slenderness in both bridge decks and suspension pylons, Dinnet’s structure is unashamedly massive. These two 1930’s crossings take their place in the evolution of bridge design, which began in medieval times with stone-arched structures like the 16th century Brig o’ Dee, which is still the entry to Aberdeen from the south. Craft construction methods were still being employed by Major Caulfeild when he built the original Gairnshiel Bridge in the 1750’s. It was supplanted by the Jubilee Bridge because vehicles repeatedly collided with its parapets as they attempted to make a switchback corner then climb over the hump. Wade and Caulfeild were followed by the master builders John Rennie and Thomas Telford.

Telford, often thought of as the father of civil engineering, built Potarch Bridge in 1814. It sits a few miles downstream from Aboyne and connects Wade’s military road beyond the Cairn o’ Mount to all routes north. Compared to the old Gairnshiel bridge, it’s a more sophisticated piece of engineering, consisting of three segmental arches carried on stone piers with refuges and cutwaters. Telford built well, and today his bridge carries 44- ton timber lorries. Telford was followed during the second half of the 1800’s by an era of scientific engineering. That was spurred by the collapse of the first Tay Rail Bridge, after which engineers wrestled with the science behind new structural materials such as cast and wrought iron. The introduction of reinforced concrete in the early 20th century led to another learning curve, and F. A. MacDonald and Partners (now known as Fairhurst) were early adopters, along with Owen Williams, who designed the brutally strange Findhorn Bridge on the old A9.

The post-War years saw the development of large span suspension bridges, such as the Forth Road Bridge, followed by large span cable-stayed bridges, including the Queensferry Crossing. In parallel, we saw the rise of the architect as leader of the design narrative in bridge design. The idea of architects taking a design lead isn’t new – consider George Bennett Mitchell collaborating with MacDonald on the Aboyne Bridge during the 1930’s – yet “bridge architect” is a niche we didn’t hear about at architecture school. Where does engineering end and architecture begin? That’s the wrong question, because they’re integral to each other, yet bridge design doesn’t immediately seem like fertile territory for architects. The best-resolved bridges are all about economy of means, truth to materials and finding the most direct path for forces to follow.

That puts dualdisciplinary architect-engineers at an advantage – figures like Santiago Calatrava, arguably the most famous bridge designer of the modern era. After graduating, I worked with an architectural practice which sometimes partnered the civil engineers Babtie Shaw & Morton, later Jacobs Babtie. The work ranged from bids for landmark projects such as the East London River Crossing or “Thames Gateway Bridge”, to the design of more prosaic structures along the Heads of the Valleys Road dualling project in South Wales. Our team lost the Thames Gateway competition to Calatrava, although in the end his proposal for a slender steel arch tied back to the deck using inclined struts wasn’t built, either.

Working alongside Babties, I learned a lot about the design process. It was neither a case of the architect conceiving a design concept then telling an engineer, “Now make it stand up”; nor the engineer calculating the structure, then expecting an architect to sprinkle magic dust over it. Instead, the design workshops were collaborative, intensive, and rarely involved a “Eureka!” sketch executed using a fat pen. Another thing I discovered was the civil engineer’s passion for curves – catenary, cycloidal and paraboloid. Sometimes the smooth curve was boiled down to a polygonal arch, which is its cut-price cousin. While Aboyne Bridge is a concrete portal frame with gracefully arched spandrels, and Gairnshiel Jubilee Bridge has subtly cambered box girders, Dinnet Bridge is faceted like an old threepenny coin. The Upper Dee can be crossed in a single span; in other settings, scale can be a challenge.

Alain Spielmann, who worked with Norman Foster on the Millau Viaduct in France noted that, “In designing such a huge bridge, we have very little experience by which to judge the scale and proportions … For Millau, we have only the scale of the hills and the width of the valley to measure the lines and the proportions of the structure.” Ultimately, bridges are only a means to an end: to improve connectivity. Connections are easy to make on the flat plains of the lowlands, but Aberdeenshire is constricted by its geography. The north–south links follow the old Mounth routes, including the Cairn o’ Mount and the Cairnwell Pass, while the main east–west routes follow river valleys. The area’s railways, including the Deeside Railway and Alford Valley Railway, also followed the rivers, but their tracks were ripped up in the 1960’s. That was spectacularly poor timing, because communities like Banchory on Deeside and Kemnay on Donside saw a 1970’s housebuilding boom which followed the discovery of North Sea Oil.

They doubled in size, and Aboyne also grew, but all the extra traffic had to go onto the roads. As the roads got busier, the bridges along Deeside carried more, and heavier, traffic than was ever anticipated in the 1930’s. Now there’s no slack in the system when a road crossing shuts; the only alternative is a long detour. Tug on a single thread and the whole tapestry starts to unravel. So the remedial works at Aboyne and Dinnet may be overdue, but Aberdeenshire Council should be commended for repairing, rather than replacing, its pioneering bridges. In a sense, we’re always aware of the road, but only its closure makes people pay attention to and care about the bridge.

|

|