Architecture Meets Art

15 Jan 2015

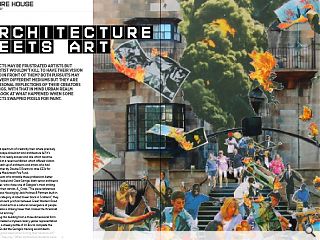

Architects may be frustrated artists but what artist wouldn’t kill to have their vision realised in front of them? Both pursuits may employ very different mediums but they are also personal reflections of their creators imaginings. With that in mind Urban Realm took a look at what happened when some architects swapped pixels for paint.

If the arts are a spectrum of creativity then where precisely upon this landscape should art and architecture lie? It’s a question with no ready answer and one which became further blurred at a recent exhibition which offered visitors a tantalising mash up of architects and artists who had gathered together by Double S Events to raise £22k for Enable and the Mackintosh Fire Fund.Two architects who straddle these professions better than most are Isabel and Clara Garriga, both senior architects at Holmes Miller, who chose one of Glasgow’s most striking landmarks for their canvas, A_Cross. “The piece references Anniesland Cross Housing by Jack Holmes & Partners built in 1969, the only category A listed tower block in Scotland,” they said. “It’s a prominent junction between Great Western Road and Crow Road and acts as a natural convergence of people and ideas. It’s also a striking tower that crosses the threshold between ground and sky.”

Abstracting this building from a three dimensional form the pair have created a stylised canary yellow representation complete with a cheeky bottle of Irn Bru to complete the composition. So did the Garriga’s training as architects stand them in good stead when turning their hands to art? “Undoubtedly,” they say. “When architecture students come to us unsure whether to pursue their degree rather than following their artistic passion they always receive the same answer ‘studying architecture provides such wide ranging skills and abilities that it will enable you to thrive in most creative professions afterwards’.” These abilities range from model making and understanding materials to ‘detailing the metaphysical process required to explore conceptual ideas, abstraction, thoughts and sensibilities’.

The Garriga’s continued: “Architecture can be defined in many ways. It can be described as the art & science of designing buildings, or the design and method of the construction of buildings and other physical structures, but some buildings are recognised as cultural symbols and as works of art. In a way architecture incorporates the knowledge of art, science and technology together with humanity.”

Rather than be hamstrung by the need to provide utility and function the Garriga’s view it as something which can enhance the seemingly less restrictive field of art. “Function always enhances architecture, even going as far back as Vitruvius where ‘utilitas’ (utility/function) stands alongside ‘venustas’ (beauty) and ‘firmitas’ (solidity) as one of the three aspirations or objectives of architecture. To understand the connection between function and aesthetic values, we must consider the concept of functional beauty. When a building is fit for its purpose surely it is a source of positive aesthetic value, especially if you compare a building to other ‘beautiful’ entities such as animals, natural environments, or items of an inorganic nature such as intricate artefacts or industrial machinery. When designing any type of building all we can try is make the functional meaningful and beautiful.”

No stranger to the end of a pencil himself Alan Dunlop is perhaps the most well-known and respected exponents of lead over silicon as a communication medium, expertise which sees him straddle the professions with uncommon agility. Outlining the inherent advantages of this approach Dunlop told Urban Realm: “Many people, including contractors and builders can deliver a building that will stand up, which meets legal requirements and will keep its users dry. There exists however a higher level of refinement which transcends function and is infinitely more difficult to create but which lifts the spirits and stimulates the senses.

“It is unquestionably better on multiple measures for people to spend their time in a building that does more than meet their workaday needs through imaginative design, clever proportion and scale, inspirational use of materials and respect for natural daylight. Human beings respond better to this type of environment through improved health and increased function – both in a productive and a social sense.

“For any architect with aspirations to create art, the challenge is to take the time to acquire skills in communication and design, to understand and respect place and context, and to become sufficiently confident of their craft - built as it is on history, precedent, creativity and inspiring construction – and above all, recognising and learning from the artistry of the many talents that came before them. Unfortunately, too many settle for the mundane-the ill-considered, and the easy option which in these straightened times are less likely to meet resistance from clients, planners or developers. The outcome is lost opportunity for practitioner and art alike.”

This train of thought was picked up by Matt McKenna, director at Dress for The Weather, albeit from a somewhat different perspective. Rather than viewing art and architecture as common strands of a single thread McKenna views them as broadly standing apart. He said: “I’d suggest architecture sits separately from the arts in many respects and for me an area of interest has been how the two come together. Traditionally buildings were created with art and sculpture incorporated into the design of the buildings themselves - within the facades, detailing and as ornament. Process, taste (and politics?) moved this away and the International Style is probably the opposite of this with minimal (if any) decoration, clean lines and only the buildings themselves viewed as sculptural objects.”

In an effort to push things forward McKenna’s own practice is exploring the interface between architecture and art; whether by ‘…bringing a kind of spatial meaning to our artwork projects or integrating artworks by others into buildings. Asked whether function compromises architecture or enhances it McKenna replied: “Architecture inherently contains some kind of function, even if that’s just rudimentary shelter. One influence within my work is the site specific sculpture that developed in America during the 1970’s and how these works although influenced by their situation also looked to alter the way people experienced galleries and spaces. Richard Serra comes to mind as an influence and Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt.

“These artists, although producing quite different works, all explore ideas around examining, creating and comparing spaces. Their sculptural work, to me anyway, is architectural in its ambition, scale and form - albeit not encompassing any specific functional programme. But the way these works alter the spaces they are in and the ideas they explore in their materiality, detail and execution has to be seen as being architecturally programmatic. Then you have someone like Gordon Matta Clark, whose Conical Intersect is an amazing example of the potential of the interface between art and architecture. This is something that manages to be architecture and art at the same time. It ceases to be a functioning apartment block and instead opens this incredible discourse on all the aspects of a building at once: structure, layout, volume, decoration, function, light and space.

“Something I’ve discussed recently are the similarities between how certain artists approach commission and the contextual response to projects that an architect might adopt. But the differences may appear in the execution of the work or the interpretation of context. The interest for me is in the complexity of the process and the variety of the response. For example, coming from an architectural background, you might assume a more structural or spatial response than an artist. However, the Powder Blue Pavilion by Toby Patterson or the Bandstand in Rieselfeld by Nathan Coley are both fantastic pieces of architecture.”

Someone well practiced in marrying an artistic eye to the built environment is architectural photographer Tom Manley, who told Urban Realm: “Architecture should aspire to exist as art in its own right, through its design process, delivery and form. Art exists for enjoyment, to inspire and inform. Increasingly its boundaries are being redefined and widened, with the digital landscape providing exposure to an endless stream of processes and practice, competing and experimenting on creative platforms.

“Has the pressure on planners and the role of ever-hungry developers and restrictive land rights enabled a surge in building that has taken ‘the art’ out of architecture? Can a new political landscape that champion’s social responsibility and equality enable opportunity for the art of engagement to deliver a new wave of inspiring places and structures? Architecture has never been more divided in terms of striving for creative expression and purpose, or simply fulfilling budgetary and functional requirements - overlooking its intrinsic value in enhancing the environment.

“’The title Architecture meets Art’ sounds like an introduction or a first date; a gentle reminder perhaps – reconnecting architects with their primal role to enhance the built environment and add to the ‘common good’, as opposed to two worlds colliding.”

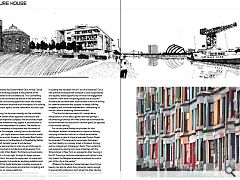

For his own piece Manley has plumped for that Glaswegian stalwart the tenement to inspire his thinking, marrying architecture with art in a literal sense before settling upon a view of a typical example, Murano Street. He remarked: “The tenements have always fascinated me, their identity is so closely linked to Scotland, forming such an integral part of Glasgow’s fabric. Their uniformity and appearance having such close similarities with the ‘Brownstones’ in New York, as opposed to other housing in the UK. Forming a continuous backdrop and rhythm to the city streets, the Glasgow tenements are almost as much a part of the city as the people.”

Whatever the balance of power between the arts true beauty may also lie where they converge; reason enough to ensure both professions don’t retreat into their silos but continue to inspire each other to improve further and faster than is possible alone.

|

|

Read next: Aberdeen

Read previous: Dunoon

Back to January 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.