Jimmy Savile's Glen Coe cottage

18 Apr 2013

In the wake of an ongoing investigation into child sex offences Urban Realm took a look around the Glen Coe home of disgraced tv personality Jimmy Savile to see whether buildings can ever be so blighted by association that demolition is the only recourse. Here Alistair Scott of Smith Scott Mullan, no stranger to the property, asks ‘do buildings have souls?’ Photography by Tom Manley.

The question of “Do amimals have souls?” seems to have regularly arisen as a theological debate from the early days of the Christian church to the present time. I understand (Googled it) that none other than Pope John Paul II specifically discussed this very topic as recently as 1990.Now this is not the usual type of weighty topic that impinges upon Urban Realm editorial meetings, but the subject of Jimmy Savile’s house in Glencoe did pop up and posed the intriguing question of how buildings would fair under such a stringent analysis.

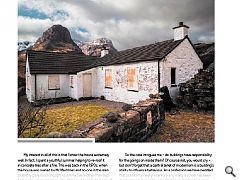

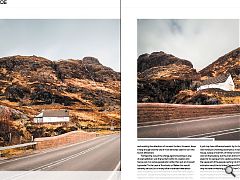

For those of you not following the story, Mr Savile owned a house in Glencoe, within which there is a suggestion of carrying out some of the deeds which are currently being investigated. The house is abandoned, has been spray painted, generally vandalised and is now a notorious local eyesore. As you might expect, there are calls for its demolition from a number of prominent local people, concerned with the impact which it has on the area.

On the other side of the debate, an alternative viewpoint (seemingly championed by well known author and mountaineer Cameron McNeish) calls for its rehabilitation as a mountaineering centre to pay back some of the wrongs inflicted within it. This case also focuses on its previous ownership by Hamish MacInnes, still a resident of Glencoe and a legendary figure of post-war Scottish mountaineering.

My interest in all of this is that I know the house extremely well. In fact, I spent a youthful summer helping to re-roof it in concrete tiles after a fire. This was back in the 1970s, when the house was owned by Mr MacInnes and no one in the glen probably gave much thought to Jimmy Savile other than that he fixed things somewhere. One of my best friends from school was MacInnes’ nephew (also called Hamish) and young Hamish and I spent our summer holidays camping in the Glen and paid for our nights of underage debauchery in the Clachaig Bar with menial labour on sheep farm and building site.

The subject under debate is a simple cottage. Local vernacular, white render, pitched roof (with some poor tiling, I must admit) and some low outbuildings. It is not grand, too near the main road to be of great value and on the various time that I drove past it over the intervening decades, I did actually wonder what the attraction was for Jimmy S. as he could easily have afforded something much better and hadn’t seemed to alter it in any obvious way.

So the case intrigues me – do buildings have responsibility for the goings on inside them? Of course not, you would cry – but don’t forget that a central tenet of modernism is a building’s ability to influence behaviour. As a profession we have peddled that position for nearly a century and many a school has been designed and many a housing estate raised and rebuilt upon it. So if buildings do indeed influence behaviour, are they accessories to the crime and deserving of punishment (or at least a good retro-fitting?)

At an extreme level – Auschwitz or Belsen or even Fredrick West’s house at 25 Cromwell Street in Gloucester - destruction was proposed and usually carried out. But hang on, what about the Tower of London, various parts of Edinburgh Castle or many of the dark closes of Edinburgh old town? It seems that if a building survives its dark deeds long enough it is rewarded with a plaque, a website and perhaps even a ghost tour. Of course much of this is to do with the impact it has on the memories of living people, helping to heal by removing macabre associations and avoiding the attentions of souvenir hunters. However, leave it long enough and the site of most atrocities seem to turn into tourist attractions.

Perhaps the core of the charge against buildings is one of premeditation; was there intent within its creation and hence was it an active perpetrator rather than just an innocent bystander? In the case of Auschwitz or Belsen this would certainly be true, but in many other instances there are so many mitigating circumstances that it would be hard to get a conviction. Usually the building had its own rationale, its own intention for other more respectable purposes and was only tainted by association.

So I would put the case that the house in Glencoe, although it just may have influenced events by its charm and position, was merely an unwitting accomplice. It was intended as a house, a place of warmth, of family fun and laughter. The villain was not the building, but the man and for that reason I would plead for its reprieve from capital punishment. I do understand the viewpoint of the people wishing rid of it, but my own inclination would be to follow Cameron McNeish’s suggestion – why not take a whacking great sum from Savile’s copious estate and renovate it to provide inexpensive, warm and welcoming accommodation to the many young people of our country who want to explore our wild places but cannot afford it.

I think buildings probably do have souls (still not sure about dogs!) and if they do I’m sure that they are redeemable.

|

|

Read next: St Albert’s Catholic Chaplaincy

Read previous: Edinburgh Colonies

Back to April 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.