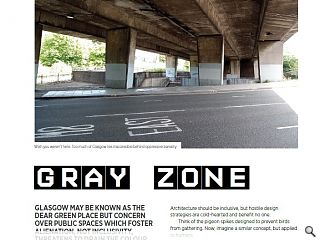

Hostile Architecture: Gray Zone

16 Apr 2025

Glasgow may be known as the dear green place, but concern over public spaces which foster alienation, not inclusivity, threatens to drain the colour from our streets. Journalist and political commentator Fuad Alakbarov calls out the insidious nature of hostile architecture.

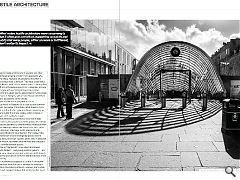

Architecture should be inclusive, but hostile design strategies are cold-hearted and benefit no one. Think of the pigeon spikes designed to prevent birds from gathering. Now, imagine a similar concept, but applied to humans. This phenomenon, known as hostile architecture, has become increasingly prevalent in Glasgow.

Despite the city’s efforts to expand public spaces over the past decade, including new playgrounds, green spaces, pedestrianised streets, and revitalised car-free zones — such deterrent features remain a stark contrast to its otherwise growing commitment to accessibility. Advocates argue that this form of urban design is essential for maintaining order, enhancing safety, and discouraging undesirable activities like loitering, sleeping, or graffiti. However, hostile architecture in Glasgow and other cities has faced growing criticism from opponents who argue that these measures are excessive and unfairly impact society’s most vulnerable. They have condemned features like so-called “anti-homeless spikes,” claiming they punish those with nowhere else to go — especially as many cities struggle with worsening homelessness crises.

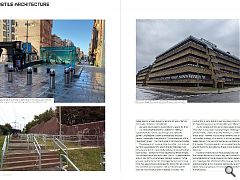

According to latest figures, approximately 7,200 people are homeless in Glasgow, with around 30 percent of them believed to be sleeping on the streets. Hostile architecture is prevalent across all neighbourhoods in Glasgow, but it’s particularly common near parks, and public transit hubs. What makes it more concerning is that it often goes unnoticed, happening so quietly and subtly that many people, either unaware or indifferent, don’t realise its impact. It’s not limited to just benches and concrete slabs; there are also spikes, pig ears, bollards, grates, and various other features designed to deter homeless individuals from resting or sleeping in alleys, near storefronts, or in parks.

For centuries, cities have constructed walls and defensive fortifications for protection. Even today, metal and concrete barriers are strategically placed around public buildings and town squares, particularly in areas like Glasgow Airport, to prevent stray vehicles and safeguard against potential terrorist attacks. Hostile architecture isn’t only aimed at homeless individuals. Skaters — and young people in general — are also seen as a nuisance by property owners, and it doesn’t take much to spot design elements intended to keep these groups at bay. The underlying idea appears to be that if an exterior space becomes more than just a passage for walking or commuting, it becomes a problem.

However, many urban planners and designers believe that promoting the use of public spaces actually brings an area to life and enhances the quality of life for its inhabitants. But who would want to spend time in a space like this?For most property owners, a sidewalk is merely a space for pedestrians to pass through, not a place to gather. Congregation is seen as undesirable, because people —especially those who aren’t considered part of the “dominant” group — can’t be trusted. It’s a troubling mindset. The elements of hostile architecture often go unnoticed by most Glaswegians who aren’t directly impacted.

Few will pay attention to these subtle features or recognise their significance. However, for those targeted by these designs, the messages are abundantly clear. Mary V., a homelessness activist and former Drumchapel resident, explains, “What you see is just a microcosm of a bigger picture. Historically, there has always been a disregard for those who are outside the dominant socio-economic culture.” She also points out that hostility toward the homeless is nothing new. Authorities in some British cities have been trying for years to make homelessness a criminal offense in different ways.

As the debate over the use of public space in Glasgow intensifies, it may seem overwhelming to challenge the private interests that are actively working to privatise these areas. However, Mary strongly believes that the most overlooked strategy is for people to actively engage with public spaces. “The key is for people to use these spaces themselves. The more people that populate the urban environment, the less effective these hostile treatments will become.”

Hostile architecture is an exclusionary practice that erodes the sense of community and reinforces the dehumanisation of rough sleepers. By raising awareness and drawing public attention to this issue, we can foster positive change at the local level, particularly at a time when there is growing public concern about addressing homelessness.

|

|