Broomieknowe Golf Club: Course Correction

26 Oct 2022

A desire to introduce younger and female members to golf has sparked a radical clubhouse design that opens up new horizons of both membership and views. We look at how Calum Duncan Architects have reimagined this most suburban of building typologies to create a more welcoming front door. Images by Will Scott Photography.

Calum Duncan Architects has completed a new clubhouse for Broomieknowe Golf Club to encourage new members and meet a surge in demand for leisure facilities as people reappraise their work/life balance.

Set within the established neighbourhood of Bonnyrigg to the south of Edinburgh the £1.7m clubhouse lies between the course and the street with the southeast frontage serving as a new front door onto Golf Course Road. Set back from the street and behind a retained car park, in deference to its domestic setting, the light grey brick clubhouse maximises landscape views to the northwest from a first-floor lounge.

A notable trend in Glasgow has been the closure of bowling clubs as membership declines and lawns lie fallow. Does a similar fate await golf clubs which fail to evolve? Calum Duncan, the founder of Calum Duncan Architects, told Urban Realm: “You can imagine what it’s like for golf clubs and sustainability and the need for a new clubhouse to make the business viable. It’s about welcoming younger members and women and opening up to community use. Broomieknowe feels less like an old-fashioned golf club and more like a flexible community space.”

This is achieved through the provision of new changing rooms, a shop, a reception area and a function suite to broaden its offer beyond the diamond jumper crowd but the process was far from plain sailing, as Duncan explained, “You don’t get a harder client than a golf club because you’ve effectively got two paid members of staff and everyone else is members.”

Recalling one packed meeting of over 250 members before the decision was taken to proceed Duncan said: “Not everyone is going to see that bigger picture going forward. Some people would just like their fees to be cheaper. Not everyone agrees and you have to try and encourage people to think about the future of the club.”

With women’s sports taking off spectacularly from Euro 2022 down, clubs are embracing a market that has been largely ignored with a slew of updated facilities. “Football is quite accessible, golf is not”, remarks Duncan. “When I say I’m designing a golf clubhouse you get sucking teeth noises but it’s about making people feel that anyone can go and everyone is welcome. It’s a game for all. It’s been booming since lockdown as an outdoor sport for exercise.”

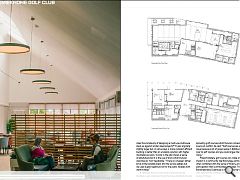

Demonstrating that golf is no longer the sole preserve of older men Duncan states: “A lot of the design was about making an atmosphere that encourages the use of the lounge by younger people who might want to hang out and have a drink or parents who come for a cup of coffee. Those uses are now relevant to the building. It’s a linear building, the front faces the street and responds to the domestic street frontage. It’s about the community’s welcome. The other side is about creating a strong connection to the course itself which didn’t previously exist.”

What role does architecture play in opening up golf to a broader demographic? What are the physical attributes which encourage people off the street? “You’ve got a welcoming stair, we make it clear where the public spaces are and make the most of sunlight and views”, says Duncan. “Even the material and arrangement of ground floor service spaces play their part. If you were to compare it to a traditional clubhouse where you immediately feel on edge’, where’s my tie, where’s my blazer, you want to open the door and feel welcome and not judged for who you are.” Pointing to a roof light as a key intervention in making this happen Duncan continues: “The roof light is about providing morning light into the space. It starts at 10 in the morning and continues through the day as the sun moves around the building. It brings character to the space.”

Banishing the members’ only perception of the sport, Duncan has encouraged the use of external spaces such as landscaped areas and a balcony to mediate between the course and clubhouse. “A lot of golf courses are guilty of setting outside space alongside a stuffy old bar”, notes Duncan. “We mediate between the external space and the professional spaces to create a place for people to sit and linger.”

Part of this process saw a shop owner (reluctantly) agree to relocate, permitting the old shop to be converted to a caddy store, a process which ultimately proved beneficial to all. “It tends to be the first and last place you go to before stepping out onto the course. He’s a much happier person because he is meeting people as they go to and from their game and he feels at the heart of it.

“It’s simple stuff, just thinking about the different spaces in the building, where they are and how they connect. In some ways, we’re trying to be quite calm architecturally and that is about the context as well as being comfortable and accessible. We use the gable as the public side while the hipped side reflects the calm working end.”

Is there a dichotomy between modernising the sport and providing new facilities in an established residential area where neighbours don’t always see eye to eye? Did you find you were constrained by a degree of domesticity? “If anything we were pushing towards the course rather than towards the street. It was about connecting with the landscape and planting trees and hedges to get the connection. We do abut directly onto the green with the canopy.” Is the bay window safe? “They used to have big screens up around the course so golf balls wouldn’t hit cars but we asked if there was another way to deal with the issue. We shunted one of the tees further up so they’re not hitting balls towards the clubhouse any longer.”

With a lot going on in what isn’t a huge building how does the complexity of designing a multi-use clubhouse stack up against similar-sized projects? “It was originally slightly larger but, in some ways, a more compact efficient building is better than an unwieldy solution with higher maintenance costs.” A kink in the plan shows a sense of playfulness but it is the use of brick which Duncan describes as ‘non-negotiable’. “There is a cheaper darker brick at the kickable areas and the service gables but we used a good quality brick for the public facades with warm timber.”

A renewed focus on the need to provide leisure facilities in our cities has thrust the focus of attention onto sprawling golf courses which Duncan concedes can be a source of conflict. He said: “Golf courses are a contentious issue because a lot of green space in Edinburgh is given over to golf courses and you could argue there are too many.”

Proportionately, golf courses can make a bigger impact in a community like Bonnyrigg, particularly when combined with the sense of history, pride and participation that such facilities engender. The new Broomieknowe Clubhouse is now on course to develop that potential by inviting a new generation to get into the swing of things.

|

|