Livingston Skatepark: Pipe Dreams

26 Oct 2022

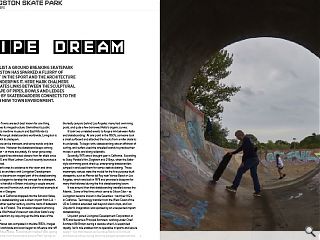

A bid to list a ground breaking skatepark in Livingston has sparked a flurry of interest in the sport and the architecture which underpins it. here Mark Chalmers investigates links between the sculptural landscape of pipes, bowls and ledges crafted by skateboarders connects to the broader new town environment.

Scotland’s New Towns are each best known for one thing. Cumbernauld has its megastructure; Glenrothes its public art. Irvine has its maritime museum and East Kilbride its roundabouts. Amongst skateboarders worldwide, Livingston is synonymous with its skatepark.

Youth culture can be transient, and some trends only last for a season or two. However the skateboard keeps coming back into fashion – or more accurately, it’s never gone away. Livingston Skatepark has attracted skaters from far afield since it opened in 1981, and West Lothian Council recently launched a bid to have it listed.

The skatepark owes its existence to the vision and drive of Iain Urquhart, an architect with Livingston Development Corporation who became an integral part of the skateboarding scene. When he began to develop the concept for a skatepark, there were only a handful in Britain: including a couple around London at Harrow and Hornchurch, and a short-lived example at Kelvingrove Park in Glasgow.

Livi is a piece of California dropped into the Almond Valley. Forty years ago, skateboarding was a direct import from L.A. – but go back another quarter century, and the roots of skatepark design actually lie in Finland. The amoeba-shaped swimming pool set into the Villa Mairea’s forecourt was Alvar Aalto’s way of softening Modernism by conjuring up the little lakes of the Karelian forests.

After Villa Mairea was completed in the late 1930’s, images were published worldwide and soon began to influence one-off houses in the United States. Scandinavian-inspired villas sprang up across California, from the arid land around Palm Springs to the leafy canyons behind Los Angeles: many had swimming pools, and quite a few borrowed Aalto’s organic curves.

It took two unrelated events to forge a link between Aalto and skateboarding. At one point in the 1950’s, someone took a small surfboard and attached the trucks from a roller skate to its underside. To begin with, skateboarding was an offshoot of surfing, and surfers used the wheeled boards to practice their moves in parks and along sidewalks.

Secondly, 1975 was a drought year in California. According to Stacy Peralta’s film, Dogtown and Z-Boys, when the Aalto-style swimming pools dried up, enterprising skateboarders jumped in and used them for some creative skating. Those impromptu venues were the model for the first purpose-built skateparks, such as Marina del Rey near Venice Beach in Los Angeles, which was built in 1978 and provided a blueprint for many that followed during the first skateboarding boom.

It was around then that skateboarding travelled across the Atlantic. Some of the firms which came to Silicon Glen – as Livingston became known in the Seventies – had their HQ’s in California. Technology transfer from the West Coast of the US to Scotland extended well beyond silicon chips, and Iain Urquhart’s imagination was sparked by an unexpected import: skateboarding.

Urquhart joined Livingston Development Corporation in 1970 and became a Principal Architect, working under Chief Architect Bill Brown during a decade when Livi expanded rapidly. Iain’s role enabled him to specialise in sports and leisure design – but that interest can be traced back to his time at architecture school, during which he enjoyed recreational rock climbing.

As a part-time student at the Mack, Urquhart won the RIBA Silver Medal in 1963 for his intermediate project, a climbing school in Glencoe. By luck, he took up climbing at the point when Dougal Haston and Hamish MacInnes led a new wave of Scottish climbers, who prepared for the Alps and Himalayas by putting up new routes in Scotland’s winter mountains.

That was Urquhart’s first realisation that architecture and sport could cross over, and he later collaborated with MacInnes on the design of the first metal ice axe, and the lightweight stretcher which mountain rescue teams still use to get injured climbers down off the hill. Iain Urquhart was in the right place at the right time.

Despite winning prizes for his student schemes, which included a project to repurpose the old Renfrew Ferry after it was replaced by the Clyde Tunnel, Iain Urquhart didn’t see eye-to-eye with the head of school at the Mack. So in 1965 he transferred to Edinburgh College of Art for his Part 2, and opted to study full time. Whilst in Edinburgh Iain met his future wife Dee, and after graduation in 1967 he went to work with Alison & Hutchison – until an opportunity came up in Livingston to design an indoor multi-sports centre.

Livingston Development Corporation’s ambitions for sports and leisure facilities should be seen in context. The post-War New Towns were intended to provide the green spaces and fresh air lacking in the crowded Glasgow tenements which many of Livingston’s new residents left behind. Ironically, then, the sports centre didn’t go ahead although Iain later worked on the construction of a Sports Barn in the town which I understand was built, but later demolished to make way for an extension to the Almondvale Shopping Centre.

Meantime, Urquhart made the most of the funding which was available, to create smaller schemes which were part of a masterplan for the Almond Valley. Urquhart’s concept for a Sports Landscape combined the trim track with a running course and exercise machines, plus a climbing wall and kayaking facility. But it was skateboarding which had captured his imagination, and for a second time, he was in the right place at the right time.

Iain and his wife Dee initiated a research trip to the West Coast of the US. By now, Dee was an enthusiastic skateboarder herself, and Iain carried his tape measure everywhere to record the geometries which worked well. Crucially, he also began to understand what didn’t work: surfaces which were lumpy, lines that didn’t flow, walls too high and bankings too flat. The transitional spaces where you turn around and compose yourself between tricks were sometimes too short, or even non-existent.

During their trip Iain and Dee made lots of contacts in the Californian skating scene and visited many skateparks such as Marina del Rey in Los Angeles and Pipeline in Upland, California. In the process, they met Tony Hawk’s father and eventually, their pilgrimage was reciprocated, when Tony Hawk travelled from California to skate at Livi in the 1990’s. By then, Hawk was world-famous – the one skateboarder whom everyone has heard of.

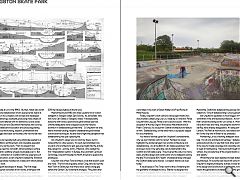

On his return to Livingston, Iain revised and developed his skatepark drawings, eventually producing many sheets of plans and sections lettered with his distinctive cursive script. At the same time, Iain and Dee threw themselves into running the Scottish Skateboard Association and producing skating magazines. Once the funding, research, promotional and design challenges had been surmounted, the next hurdle was construction.

Skateparks are typically built using shotcrete applied to a cage of mesh fabric reinforcement, and nowadays specialist contractors carry out the work. From his research Iain understood the need for a smooth, almost polished, surface so that the boards’ urethane wheels would glide over it. But there were no contractors in Scotland with any experience of skatepark construction, so Iain Urquhart created the Transition Machine – a steel blade mounted on a radius arm which planed the face of the bowl.

Livi’s skatepark developed in stages. The first stage which Iain designed consisted of twin bowls, a half pipe with a flattened base, plus the the Andover Bank and a reservoir feature. They were later joined by a freestyle area and finally in 2015 the full pipe feature at the far end.

Meanwhile around 1980, Iain drew up plans for an indoor skatepark in Glasgow called Zero Gravity. As Jamie Blair, who now runs Clan Skates in Glasgow, noted, “It looked pretty awesome with various pools and a giant banked reservoir. Unfortunately plans were scrapped due to the massive downturn in skateboarding at that time.” So Urquhart not only had to marshal funding, research skateboarding and master construction techniques: he also had to fight the perception that skateboarding was just a passing fad.

Iain Urquhart’s career was cut short by illness, but it’s noteworthy for a few reasons. His work demonstrates how crucial it is for architects to gain genuine insight into the activity they design for. Just like John L. Paterson, who created the first “interpretation centre” in Europe, the Landmark Centre at Carrbridge, Urquhart travelled to North America to explore the prototypes.

Urquhart was a New Town architect, a role that doesn’t exist any more. The first was arguably James Craig, who laid out the New Town in Edinburgh, then there was a century-long gap before the Garden City movement emerged. Fifty years after that, the post-War New Towns were conceived, with five built in Scotland plus the stillborn Stonehouse. Those New Towns culminated in the work of Derek Walker and Fred Roche at Milton Keynes.

Finally, Urquhart’s work came to notice again thanks to a documentary called Long Live Livi, made by co-directors Parisa Urquhart and Ling Lee; Parisa is Iain’s second cousin. With the exception of Murray Grigor’s films about Mackintosh and St Peter’s Cardross, it’s unusual for Scottish architecture to feature on film. Skateboarding, on the other hand, is a popular subject for documentaries.

You have to wonder, given Iain Urquhart’s achievements, why we aren’t familiar with his name? Perhaps his career highlights the divide between two worlds: architecture and skateboarding. As Jamie Blair of Clan Skates explained, “Iain and Dee’s work in the early days was fundamental to the Scottish and GB skate scene. They truly led the way in so many areas, and the design and construction of Livi skatepark (during the late 70’s and early 80’s “death” of skateboarding) changed the Scottish skate scene forever. Livingston stands out even today.”

A recent piece in The Times went further, christening Iain the godfather of skateparks since, “Before he designed the Livingston Skatepark, built in 1981, there wasn’t much evidence that the architects had involved skaters in their concepts.” Meanwhile, Californian skateboarding pioneer Stacy Peralta called him, “One of skateboarding’s unsung prophets”.

Iain Urquhart’s reputation is much bigger in the skating world than in the architectural profession. As for his legacy, that’s where the listing bid for Livi comes in. Most skateparks have short lives and many, including the world-famous Marina del Rey, have already disappeared. An early park outside London, The Rom at Hornchurch, was listed a few years ago; so far it’s the only one in Britain to be protected.

Maintaining Livi as a working skatepark has a serious side. It’s not only architectural heritage – skateboarding is a grassroots activity in a way that most other sports left far behind in the race for media coverage and corporate cash. Yet Livi is in need of maintenance. Having living through forty Scottish winters, the concrete face of the original bowls is cracked, pitted and “gnarly”.

Whilst there has been debate amongst skateboarders about resurfacing it, I’m sure the best result will come from sticking to Urquhart’s original philosophy: actively involve skateboarders in the design and construction of skateparks, which in this case means the generations of skateboarders who grew up at Livi.

After all, they still ride the vert, grind the cope and give big props to Iain Urquhart, the godfather of the skatepark.

|

|