Timber Supply: Breaking the Logjam

12 Jul 2022

Large vertically integrated sawmills are streamlining timber processes, freeing up stressed supply chains by capitalising on native timber right where we need it most. Mark Chalmers goes behind the logistics to preach the virtues of self reliance in a homegrown industry.

The great events which move history also affect our day-to-day lives. Putin’s horrific war in Ukraine soon led to a shortage of Siberian Larch, which timber merchants either stopped stocking or couldn’t import into Scotland. Since Siberian Larch is a favourite cladding material, we had to break the supply chain and consider homegrown alternatives, such as Scottish Larch, instead. Importing Russian timber into Scotland is an ancient trade. For centuries, ships from Archangel called at ports on the east coast including Leith, Montrose and Dundee with breakbulk cargoes of softwood.

Before the First World War, almost half of Britain’s timber imports were supplied by Russia: the Bolshevik Revolution cut them off overnight and the pressure to become self-sufficient gave birth to the Forestry Commission. A century later, history repeated itself. Meantime, engineered timber gained traction as we chose more sustainable ways to build, although the vast majority of cross-laminated timber (CLT) comes from Germany and Austria. But CLT imports have been hit by the effect of implementing Brexit: the smoothly-flowing supply chain which once saw container trains speeding through the Channel Tunnel to Eurocentral has juddered to a halt. In this case, it’s a trade dispute rather than war which broke the chain. In the background, climate change is blamed for the increasingly frequent and powerful storms which hit Scotland each winter.

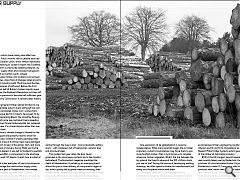

Scottish Forestry estimated that 8000 hectares or around 16 million trees were damaged or laid flat by Storm Arwen in November 2021, and more followed at the end of January during Malik and Corrie. When the storms abated, it was left to Scotland’s sawmills to deal with the windfall; in comparison to the shortage of Siberian Larch and CLT beams, there’s now a surfeit of Sitka Spruce. These are just a few examples of how circumstances combined to sabotage the construction supply chain. Its fragility is due in part to Globalisation, the concept of unfettered movement and free trade.

Cultural globalisation means sitting on your IKEA couch wearing a Uniqlo T-shirt and streaming the Squid Game on your iPhone. In construction terms, it means convoys of ships sailing through the Suez Canal – and occasionally getting stuck – with containers full of heat pumps, ceramic tiles and structural steel. The incident last year when the Ever Given grounded in the canal was a portent, and a few months beforehand, The Economist magazine predicted the death of Globalisation. It picked up an emerging trend where the just-in-time delivery of components began to slip, which quickly led to global trade un-winding, then manufacturers began to re-shore production which they’d previously off-shored.

The metaphorical drawbridges were drawn up, and suddenly De-Globalisation became a thing. One expression of de-globalisation is resource independence. While many sawmills began life as timber importers, current circumstances may force them to use more Scottish timber. That in turn forces us to consider where our timber originates. What’s the link between the log piles at the forest’s edge and the 100 x 50mm studs you see on site? During the course of developing working drawings, we often speak to timber kit manufacturers but rarely visit the places which feed them. The largest sawmills and processing plants in Scotland are owned by three groups: Donaldsons, BSW and James Jones.

The Donaldson Group grew out of James Donaldson & Sons the timber merchants, and now encompasses timber engineering, builders merchants, interiors and fit-out firms. Donaldsons recently acquired Stewart Milne Timber Systems which gave it a major slice of the timber kit fabrication industry. BSW is the UK’s largest sawmill operator and was recently taken over by Binderholz, the Austrian producer of cross laminated timber. Its purchase enables Binderholz to make CLT and other solid laminate timber products here, rather than having to import everything into Scotland as its Continental competitors KLH and Stora Enso have to do. BSW have mills at Boat of Garten near Aviemore, Kilmallie near Fort William and Earlston in the Borders.

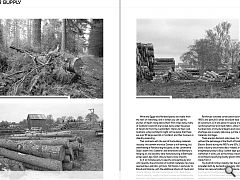

James Jones & Sons operate the largest sawmill in the UK, at Lockerbie, and also own mills in Huntly and Fochabers plus Burnroot near Aboyne and Ladywell near Kirriemuir. Burnroot specialises in timber for construction – such as rough-sawn timber and regularised PAR (planed all round) timber. David Leslie of James Jones noted that Burnroot was built in 1962 and has been upgraded and modernised several times, as its production gradually moved from railway sleepers and pit props to timber for construction. Carcassing, as framing for the construction industry is known, now makes up around two-thirds of Burnroot sawmill’s production. The demands of the CNC machines which produce gang-nailed trusses and structural insulated panels (SIP’s) mean that sections of timber need to be longer, truer and more uniform than in the days of stick-built construction.

As with steel fabrication and precast concrete production, timber processing is increasingly automated with lasers, robots and even artificial intelligence installed in modern sawmills. Despite the scale and sophistication of their operations, both James Jones and Donaldsons are still run by the families which founded them. That’s a rarity in the globalised construction industry, which is dominated by stock market-listed firms and multi-nationals controlled by private equity. Perhaps the process of de-globalisation will have an effect on business ownership; meanwhile in the tier below the big three are smaller, also family-owned, sawmills such as Cordiners at Banchory, Gordons in Nairn and Carrbridge, and also Russwood at Newtonmore.

The growth of the sawmill groups was a response to a combination of increased demand and increased supply. Economic forestry began as a way for the Forestry Commission to replenish forests felled during the Great War, and to provide resilience after imports from Russia dried up. The timber harvested forty years later was used to feed the paper pulp mill at Corpach near Fort William – but thanks to globalisation and the “paperless society”, most of Scotland’s paper-manufacturing disappeared at the start of the 21st century. Construction expanded to fill the gap. Over the past half-century, housing in Scotland has shifted from predominantly cavity masonry construction to around 85% timber kit.

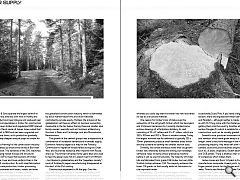

During the masonry era, timber was a low value commodity used mainly for framing and cladding, whereas you could say that the timber has now recovered its role as a structural material. One reason for timber’s loss of status was the exhaustion of the old growth timber which the Georgians and Victorians had access to. I recently studied some archive drawings of a Perthshire distillery, its roof consisting of 10 x 4” rafters and 12 x 3” collars, which are 250 x 100mm and 300 x 75mm in modern money. Today the largest nominal size for softwood is typically 225 x 75mm: plantations produce small diameter boles which are only suitable for sawing into smaller section sizes. Similarly, old school architects knew that old growth timber was inherently dense and strong, but nowadays softwood relies on being stress-graded by machine before it can be used structurally. The majority of timber kits are fabricated from grade C24 timber, but very little Scottish timber achieves C24.

The majority achieves the lower C16 grade: so that usually leads kit fabricators to use imported timber. Nonetheless, C16 is fit for most aspects of timber-framed construction, and it’s perfectly possible to construct a timber kit using Scottish timber throughout, usually homegrown Sitka or Norway Spruce or occasionally Scots Pine. If you need a larger or stronger section, there are engineered timber beams such as Kerto and Parallam – although neither is made in Scotland, so as with CLT they come with the challenge of physically getting them into the country.

Another alternative is large section Douglas Fir which is suitable for post-and-beam construction, and can be visually graded to C24. Sawmills once produced mountains of wood chippings and sawdust which were given away to a good home. No longer: there’s very little wastage in the modern timber-processing industry. Any wood left over from milling battens, studs and joists becomes engineered products such as JJI joists, chipboard, Glulam beams, CLT beams and OSB panels. There is another, inter-connected group of companies which makes them. James Jones and Sons’ JJI plant in Forres manufactures composite I-beam joists, typically using finger-jointed spruce for the flanges and OSB for the webs. There’s also Norbord who make Caberboard chipboard at Cowie near Stirling, Egger at Barony in Ayrshire which runs a chipboard and wood recycling plant, and a second Norbord factory which make Sterling Board OSB at Dalcross just outside Inverness. While the Egger and Norbord plants are visible from the train or motorway, and in winter you can see the plumes of steam rising above them from miles away, many of Scotland’s sawmills are tucked away under the eaves of forests far from the Central Belt. Thanks to their rural locations, urban architects might not be aware that there are over 80 large sawmills in Scotland, and their business is steadily expanding. That contrasts with the rest of the building materials industry: the cement works at Dunbar is still working, but steelmaking at Ravenscraig has gone, as has Lanarkshire Steel’s beam mill. Scotland’s last brickworks at Blantyre is hanging on, but sanitary ware manufacturing at Barrhead ended years ago.

Each closure means more imports. So it isn’t always easy to specify conscientiously and until recently, the promotion of Scottish materials may have seemed like a patriotic gimmick. Yet thanks in particular to Brexit and Ukraine, with the additional shocks of Covid and climate change, the stars have aligned. Cost, lead-times, carbon intensity, quality, transport issues and bureaucracy all point to the need to specify local materials, and there are historic precedents for the fix we find ourselves in. Reinforced concrete construction boomed in the 1950’s and early 60’s when structural steel sections were at a premium, so it was easier to secure a few tons of reinforcement bar and mesh fabric, rather than a few hundred tons of structural beams and columns. The steel shortage was a supply-side issue, just like many of today’s materials shortages.

There are also demand-side issues. For example, without the patronage of the North of Scotland Hydro Electric Board during the 1950’s and 60’s, Scotland’s natural stone industry would have died. Instead, the Board’s enlightened policy to Buy Scottish kept quarries open and craftsmen in work, just as the timber industry today relies on architects specifying locally-grown timber and products made from it. The Scottish timber industry has the advantage of being propelled both by demand and supply. Using more native timber can reduce Scotland’s dependence on imports, and improved technology enables sawmills to use a greater proportion of the harvested timber. All that remains is for architects to specify Scottish in a conscious way to break the chain of globalisation.

|

|