Placemaking: Garden City

20 Oct 2021

Local authorities are under constant pressure to build ever more new homes, often in the form of large housing estates developed by private sector volume house builders. However, the rush to deliver housing numbers to meet government targets, is often at the expense of neighbourhood building, identity, character and urban design quality. Leslie Howson assesses some of the key issues surrounding this sector of the housing market and looks at the merits of the first phase of the Edinburgh Garden District.

The release of greenbelt land from areas around our cities to provide space for housing is often a controversial issue. There are concerns about the controls over where housing is built and about the issues of land supply and the power exerted by the private sector set against the planning system and government pressure on local authorities to build more houses. Housing density versus land use is inevitably also an issue. Should housing simply be allowed to sprawl into the green belt of the Scottish landscape or should there be a greater degree of densification? Also, should urban expansion be such a developer and landowner led process, which is often a piecemeal approach to urban expansion, or should we expect more comprehensive urban planning from our city authorities?

For many, current planning controls in Scotland are inadequate. The Scottish planning system is still largely developer-led. In the speculative housing sector, private land ownership together with local political support gives the power to build. Housing allocations in Scotland are controlled under regional strategic and local development plans. Planning advice notes give supplementary guidance to direct developers towards good design. However, it is land supply that is the major controlling factor and influence on the volume housing market. Currently, volume house building in the UK is dominated by a handful of house building companies who bank land while seeking planning permission for large scale housing developments.

Owing to government housing targets and pressures on local planning authorities, it has become increasingly difficult to refuse planning permission even where the proposal is contrary to the local development plan and whether or not it is sustainable, sustainability being often accepted simply on the basis that the site adds to the land supply for housing. Apart from this, there is among many urban designers, planning authorities, environmentalists and affected communities, the view that many large-scale housing developments around continually expanding cities like Edinburgh are being churned out without proper regard to the quality of placemaking, the creation of sustainable communities, appropriate land use and the impact on the wider landscaped context.

The demand for housing and the response of the development sector continues apace but the results are often large swathes of new housing estates simply achieving numbers of houses as a saleable commodity but lacking distinctiveness, identity and character. In effect, as new settlements in all but name, they are often built without any attempt to create communities or neighbourhoods. Much of this volume housing is soulless, typically comprising rows of identical neo-traditional houses, as a consumable product, the developer marketing to supposed consumer aspirations for detached homes (the Englishman’s home is his castle syndrome). These housing estates largely serve the car reliant family demographic who seem happy to live cheek by jowl in their detached villas, within touching distance of their neighbour`s house. Unlike the more community-minded Scandinavians and other Europeans, building mixed demographic housing estates is not the aim of the handful of major house builders in the UK.

They aim to sell as many house units as possible. The consumer can pick from a variety of house sizes but the style and design are almost always neo-traditional as it has been for the past 50 + years. Seemingly there is no appetite to depart from that model and no room for significant architectural innovation which might otherwise redirect attention to seek more carbon-conscious concepts and tighter less land gobbling developments. Master planning and formulation of urban design frameworks can make for successful developments but need to be complemented by sound quality design criteria and careful land use and character zoning of the site at the outset. The approach to much master planning in current volume housing often results in simply a jigsaw of housing plots with no consideration of the character and with the worst master plans offering no more than a seductive illusion of urban design. It is important to create places where people want to be and can flourish and this is nowhere more true than in the area of speculative volume housing. The importance of placemaking cannot be overstated. It gives identity and legibility to our cities and towns and where we live thus is key to successful residential developments and ultimately is important to our health and wellbeing.

Thankfully, placemaking is now firmly embedded in the Scottish Planning system and is one of the two Principal Policies of Scottish Planning Policy and aims for the creation of sustainable, well-designed places and homes, which meet people’s needs. Housing and place are seen to have an important effect on our lives, health and wellbeing. Creating high-quality places is seen as helping to tackle inequalities, allowing communities to thrive. Places that are well designed, safe, easy to move around, offer employment and other opportunities and with good connections to wider amenities will help create vibrant sustainable neighbourhoods for people to live, work and play. The notion of placemaking is not new and is certainly not new to urban designers for whom it is an inherent part of any urban planning process. Urban design principles on all large-scale housing developments are key to placemaking and creating sustainable new residential communities. Building in character zones is also an important element in successful master planning to provide local neighbourhood identity and legibility over the site. Such zoning requires consideration of variable building heights and densities, scale and architectural character.

A major consideration in the master planning of large-scale residential developments, is now, more than ever, resilience to the effects of climate change. Not only can climate resilience measures dictate the eventual spatial form of the master plan but they can set the course of urban transformation many years ahead, some master plans being built over a decade. It is thus important to evaluate climate risks early in the master planning process, focusing on the physical impacts of projected climate change that are relevant to each particular site. Remediation measures to counter potential flooding of the site is perhaps the most obvious issue and the importance of which is still often underestimated. To better control carbon dioxide emissions, reduce dependency on fossil fuels and reduce fuel poverty, there is potential for inclusion of district heating and network systems in the larger housing developments, something very much in focus now with the likelihood of cities like Edinburgh moving ahead with the ban on gas boilers in individual homes by 2025.

A significant outcome from life during the global pandemic, is the extent to which provision of open space has a critical role to play in maintaining mental as well as physical health, stressing that access to both private and shared amenity green spaces is desirable in large housing developments to strengthen the connection between homes and nature. EMA Architecture + Design Limited`s Redheughs Village project, the first phase of the huge new Garden District development in the west of Edinburgh, is tackling key aspects associated with large scale housing developments and with specific regard to the housing needs of Edinburgh. Inspired by its proximity to the city, the Garden District is being seen as an important cornerstone in delivering much needed new housing for Edinburgh and is likely to be one of the most significant housing development projects in Scotland. Seen as an unrivalled development opportunity, Edinburgh’s Garden District is majority-owned or controlled by Murray Estates and will provide the much-needed future housing supply for Edinburgh.

The managing director of EMA describes this as an enormously complex site, sitting between a designed landscape, the city bypass and the A8. Meeting Edinburgh’s housing needs is a huge challenge and EMA believes the Garden District has been carefully planned to be a sustainable way of providing a genuinely world-class extension to Scotland’s capital. To achieve a successful outcome, the design for the new neighbourhood will make connections to both Edinburgh Park and Edinburgh Gateway Station & Transport Interchange while addressing the environmental effects of the major roads defining its boundaries and aims to create a quality environment within the site suitable for a new community and with a specific sense of place. Extending to 675 acres (250 ha), the Garden District will provide up to 6,200 new family homes offering a mixture of housing types and tenures and of which 25% will be affordable housing. The new homes will be for families who wish to live close to employment and shops and with good accessibility and connectivity to the city.

All parts of the scheme will embrace sustainability principles, providing access to infrastructure that will include a new primary school, a neighbourhood centre and health facilities. Convenience shopping will integrate with existing communities delivering inclusive growth and improved connectivity. Active travel will be encouraged through existing and improved public transport, pedestrian and cycling networks. The new homes will be complemented by a mixture of supporting uses and facilities including high quality shared public green spaces. The Garden District Master Plan has been devised around the creation of six new connected districts each defined as a village, one of which, Redheughs Village, will form the first important phase of this new community and will deliver up to 1,350 new homes. The village will be ideally placed to provide a mixture of housing types, densities and tenures to support the nearby business communities at Edinburgh Park which are within walking and cycling distance of the site.

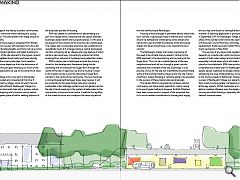

The site benefits from ready access to public transport links. A broad mix of house types is proposed from flatted blocks to 5-bedroom houses with densities from 40 to 80 units per hectare. Building heights and forms will vary across the site, with the highest densities and tallest buildings to the western edge of the site adjacent to the bypass, around the school and neighbourhood centre and lower density housing towards the countryside edge. Such variation will thus be a welcome departure from the dominance of builders’ standard house types making up so much of the new housing developments we see on the outskirts of cities like Edinburgh. Redheughs Village is thus only part of the Garden District that is allocated and consented at this time. If and when the remaining villages come forward, they are envisaged to be self-sufficient. Redheughs Village is to incorporate a local community hub with a primary school, neighbourhood shopping and a business unit as well as extensive public green space all within walking distance of the proposed pockets of housing. EMA has stated its commitment to placemaking as a part of its design ethos, believing that the spaces between buildings create vibrant and successful places. To this end, a key aspect of the scheme will be how the site is landscaped.

The master plan incorporates extensive new parklands and woodlands much of it arranged along a central landscaped corridor connecting all six villages and a key feature of which will be a new canal way. Connectivity will also be further enhanced by a network of cycleways and pedestrian routes. EMA’s master plan is landscape led with the primary driver for the development framework being the de-culverting and re-routing of the Gogar Burn through the centre of the site. In opening it up and re-routing it closer to its original course, it puts the naturalised Gogar Burn corridor in the centre of the community. The burn becomes a connecting element between larger open spaces, it will be connected to the green & blue networks including sustainable urban drainage systems and rain gardens across the site. It lends meaning to the system of safe routes to the new primary school and local centre, it adds to the legibility of the street structure and underpins the sense of place of the new community at Redheughs. Housing will be arranged in perimeter blocks around the burn corridor. A guiding principle is that the burn corridor should be defined and contained by active streets and community uses and that the majority of the transverse streets and lanes should have a view towards the burn corridor.

The Redheughs master plan takes cognisance of the need to be climate change resilient. Central to the EMA approach is the deculverting and re-routing of the Gogar Burn. This is to be a notable feature of the new neighbourhood and will run through a green corridor extending the full length of the site. Seemingly, it is to provide a focus for the site but importantly should eliminate some of the existing flooding issues across the site. Future-proofing to reduce flooding is certainly going to be essential to the success of these master-planned proposals. The Garden District proposal has not been without controversy and some public opposition, mainly owing to its use of green belt land. However Scottish Ministers have been unequivocal in support of the proposals due to its much-needed contribution to housing land supply and as a key contributor to solving Edinburgh’s housing shortfall. A planning application in principle was submitted in September 2015 for Redheughs Village as the first phase of the Garden District and was approved by the City of Edinburgh Council Planning Committee in 2016. The development finally secured Scottish Ministers’ Resolution to Grant permission in May 2020.

The success of any large-scale residential development depends on a master plan which can be prescriptive in respect of both urban design and architectural design, especially in those areas which will make it a distinctive place for the inhabitants. EMA have produced a unique and comprehensive master plan for Redheughs Village; a high-quality design creating a landscape context for housing and addressing the issue of placemaking, as well as contributing to the housing needs of Edinburgh. However, the eventual success of Redheughs Village as a place that achieves more than simply housing people, will depend on the delivery of all the key aspects of that masterplan and on EMA being able to maintain influence over the design quality of the housing and other buildings, especially within the already defined character areas.

|

|