Architecture Fringe: Salt of the Earth

26 Jul 2021

The climate crisis provides fertile ground for the Architecture Fringe Unlearning programme which seeks to upend the status quo. Among those championing change is Phineas Harper who believes the solution to ever rising carbon emissions lies beneath our feet. Can soil help clean up our dirty habits?

The Architecture Fringe is back in action with a programme of events based on the concept of ‘unlearning’ entrenched architectural tropes to eliminate behaviours and biases affecting everything from maintenance to diversity and climate.

Running over 16 days (Un)Learning heard from practitioners including Enough!, Neil Pinder, Missing in Architecture, Migrant’s Bureau and Decolonising Architecture to match the increasingly urgent need for change with a growing desire among those in the field to do things better.

Explaining the need for intervention Fringe co-director Liane Bauer said: “The programme investigates the defining issues of our generation, from whiteness, race and capitalism, to how we use and care for the land. As built environment professionals we are asking how do we change our behaviours and biases to work in a more ethical, holistic and sustainable way?”

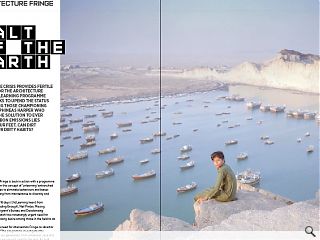

Opening proceedings for with an address on (Un)caring Phineas Harper, director of Open City, made an impassioned call for architecture to be refashioned from the ground up, chiefly by rediscovering the value of earth as a construction commodity. Echoing the enthusiasm of RIBA Gold Medal Winner David Adjaye for the treasure beneath our feet (see pg 58) Harper makes the back to basics case to save the planet to save ourselves. “Of the (1,121) World Heritage Sites more than 160 are built wholly or partially from earth. For 10,000 years earth has been one of the most widely used construction materials on the planet. What’s weird is that despite its vanishingly small carbon footprint earth is almost completely absent from contemporary architecture, young architects are rarely being tutored in how to design with adobe (mudbrick), cob or rammed earth. Instead, we are generally trained to use a narrow catalogue of highly processed, carbon rich materials such as cement which accounts for 7% of global carbon dioxide emissions.”

Tackling head-on the single biggest criticism of earth, that is to say, the regular maintenance required to keep it in shape, Harper turns things around by framing this weakness as a strength. “The materials which define our built landscape have often been chosen not for their ecological value but simply to do one thing, to reduce the burden of periodic maintenance. Thatched roofs have been tiled over, green spaces paved over and tarmac poured over cobbles. In construction, there is a consensus that repairing things as little as possible is an important goal. When a material weathers badly we’re quick to chastise the architect for not having had the foresight to anticipate this deterioration and specify a more hard-wearing material.”

Citing Peter Barber’s Donnybrook in London as an example of how skewed our priorities have become Harper points to the outrage of critics who pointed to the peeling paint and flourishing mould growth as illustrative of the follies of designing bright white buildings for a damp northern climate such as the UK. “We claim that a careful architect anticipates maintenance requirements, and designs to avoid them”, he says.

“But I think this is the exact opposite of careful. To be full of care should mean to be very willing to check in with whatever we are caring for and demonstrate our care through many small acts of restoring and cultivation rather than seek to reduce our caring obligations entirely from the outset. That is not careful at all, that is careless. That is (un)care.”

Instead, Harper turns traditional arguments on their head, pointing out that a desire to not maintain and care for the fabric of buildings once they are built is can be viewed as ecologically and socially toxic. He explains: “It’s hard to think of many examples where this desire to not show acts of care is seen as a positive but it’s easy to think of the opposite.

“Think of a parent continually checking their new born child. Think of love-smitten teenagers who text and call each other hourly. Tink of the pious disciple who prays frequently to their God. Think of the gardener who must periodically prune, pick, water and weed. Metaphors aside there is a strong ecological case to turn our backs on hardwearing materials and embrace an architecture of care and maintenance.”

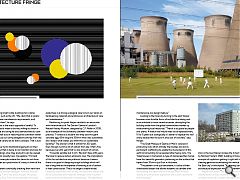

Reinforcing his point Harper recollects an encounter with the architects of The Darwin Centre in London’s Natural History Museum, designed by C.F. Moller in 2009, as an example of the dichotomy between rhetoric and practice. “I visited as a student and they said this giant concrete egg, 60m long and 300mm thick was sustainable and I asked ‘what makes you think this is a sustainable building?’ The answer is that it will last for 200 years. Even though it emits a lot of carbon from day 1 that’s fine because over 200 years that’s a low amount of carbon.

“It sounds sensible but it isn’t. We don’t have 200 years. We have to reduce carbon emissions now. The implications of this for architecture are profound because it means there is no good in designing tough buildings which will last a long time at the expense of emitting a lot of carbon in their construction. That’s no longer a viable model. Longevity robustness and solidity, the seductive values that we’ve associated with materials strategies over the years might have to be rethought or abandoned. The alternative to this is an architecture of care that requires constant maintenance as a design feature.”

Looking to the future by turning to the past Harper foresees more humble forms of architecture taking root as an antidote to more recent excesses, decoupling the building trade from the global commodities market by rediscovering local resources. “Thatch is as global as people and plants. A thatch roof would need to be replaced every 10 to 15 years but ecologically it’s better to replace this roof every decade than to build it once out of concrete,” says Harper.

“The Great Mosque of Djenne in Mali is covered in protruding rods which animate the facades and act as permanent scaffolding to enable the mud exterior of this earth brick building to be repaired after heavy rains. The Toleq houses in Cameroon (a type of domed earthen home) have this beautiful geometric patterning on the surface that tapers from 30cm to just 5cm in thickness.

“This pattern is not just decorative, it is also a three-dimensional ladder that allows residents to clamber over the building and repair the mud facade. Both invoke a duality, an architectural expression that is both decorative and functional.”

Conscious of the need to avoid being seen as an old stick in the mud Harper invokes the hi-tech style embodied by Norman Foster’s HSBC building in Hong Kong as an example of capitalism getting it right with its rooftop cleaning gantries accentuating the vertical thrust of the Far East city’s virile skyline. “If cleaning can be a source of architectural expression why can’t maintenance as well?

Harper concludes: “Our addiction to minimising maintenance is a toxic desire to not care. If we’re going to (un)learn things let’s unlearn that desire and embrace slow, steady incremental and constant acts of care.”

|

|