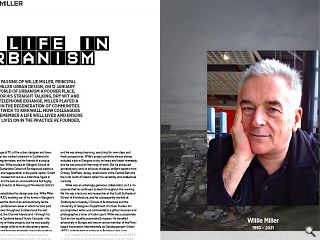

Willie Miller: A Life in Urbanism

21 Apr 2021

The shock passing of Willie Miller, principal of Willie Miller Urban Design, on 12 January left the world of urbanism a poorer place. Popular for his straight talking, dry wit and eye for a telephone exchange, miller played a lead role in the regeneration of communities from Prestwick to Kirkwall. Now colleagues rally to remember a life well lived and ensure his legacy lives on in the practice he founded.

The death, at the age of 70, of the urban designer and town planner Willie Miller has robbed urbanism in Scotland of a remarkable and singular talent, and his friends of a unique and much-loved man. Willie studied at Glasgow School of Art and the Scott Sutherland School of Architecture before a career in planning and regeneration in the public sector. Smart suits and fast cars marked him out as a distinctive figure in local government, and he was an unconventional but highly regarded Assistant Director of Planning at Monklands District Council.

In 1996, Willie established his design practice, Willie Miller Urban Design (WMUD), working out of his home in Glasgow’s West End. It marked the start of an extraordinarily fertile and wide-ranging professional career in which he took part in hundreds of studies throughout Scotland and the rest of the UK, in Ireland, the Channel Islands and – through his connection with the Spokane-based Studio Cascade – the USA.

Willie led many of these projects, but he was equally happy to offer his design skills to multi-disciplinary teams where his unique contributions invariably raised the creative and intellectual bar. He was in constant demand because he never sold his clients or his colleagues short: he could be challenging, but his passion for his work was never in doubt, and he was always learning, searching for new ideas and fresh perspectives. Willie’s project portfolio almost always included a job in Glasgow, a city he loved and knew intimately, and he was proud of that body of work. But he produced extraordinary work in all kinds of places: brilliant reports from Orkney, Sheffield, Jersey, small towns in the Central Belt and the rural south of Ireland reflect his versatility and intellectual curiosity.

Willie was an unfailingly generous collaborator, so it is no surprise that he continued to teach throughout this working life. He was a lecturer and researcher at the Scott Sutherland School of Architecture, and he subsequently worked at Strathclyde University’s School of Architecture and the University of Glasgow’s Department of Urban Studies. An accomplished writer and commentator, a gifted musician and photographer, a lover of motor sport, Willie was a passionate Scot and an equally passionate European. He travelled extensively in Europe and was an active member of the Paris-based Association Internationale de Développement Urbain (INTA), contributing to projects in Bordeaux and Lyon.

Ines Triebel, an urban and regional planner, joined WMUD in 2005 and she is carrying on the business. Ines and Willie married in 2018. Their daughter, Maxi, is two years old.

Eulogies:

It was July 1979 and my first day at work as a Trainee Planner in Coatbridge. Thatcher was PM and “Planning for Decline” was the order of the day.

The Planning Department was housed in a large, red sandstone villa and this is where I would first meet Willie. He was Principal Planning Officer leading a small team on land renewal and regeneration projects. Wim, as he was known, offered hope among the grimness - things could be improved through collaboration and smart design.

We worked together on residential schemes aimed at bringing new life to redundant buildings and vacant sites. I would do the dull site assembly stuff and he would ensure a high quality of design in the final proposals. He instigated an architectural awards scheme and I have vivid memories of him escorting the judges including Izi Metzstein to look at mansard roofs, office extensions and farmhouse conversions.

Willie had style ... his clothes, his Alfa Romeo GTV 6, his sketches, even his handwriting exuded elegance. He also had a wicked sense of humour and a favourite ruse was to pretend to fall asleep while driving, usually while overtaking on the M8!

Several times a year Willie would arrange office nights out in the West End. We would visit places like the Rubaiyat, Bonhams, the Chip and the Cul de Sac. Then he would announce we were going back to his for “loud music and nippy sweeties”.

I miss those days and I miss him.

Michael Donnelly

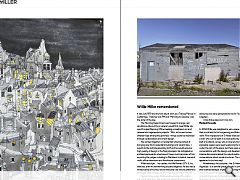

In 2004 Willie was delighted to win a piece of work in Jersey that would add to his burgeoning portfolio of urban character work. First impressions of St Helier were seductive, but for a man who cut his teeth in a local authority in the Central Belt of Scotland, Jersey was a novel environment. Many enjoyable weeks were spent exploring the town and getting under the skin of the place, but there were also challenging conversations with the design and development community, intense discussions about the role of public art, and quizzical conversations about social structures. The culture shock appeared to be two-way!

Nonetheless, the outcome - the St Helier Urban Character Appraisal - is a seminal piece of work. It contains an exhaustive and nuanced analysis of place, but during the study Willie also produced an eloquent appreciation of various local brutalist structures (to the bafflement of some of course), a ferocious critique of certain developments that were seen to be disrespectful of place, and even an analysis of the locations used in the TV series Bergerac. Some of this was admittedly rather provocative and it didn’t all make it into the final report, but it did help test our preconceptions and push the boundaries of the work.

His inclination to resist conventional approaches, as well as his creativity, intellectual curiosity and drive to continually enhance his craft inspired those of us who worked with him and will be sorely missed. As will the wicked sense of humour.

Janet Benton

One of the first projects I worked on with Willie was a town centre masterplan for Dawlish in Devon. I remember how honoured I felt to be part of a small team with Willie and other respected and experienced folk.

During our initial community consultations, a recurring issue was traffic and pedestrian conflict on the town centre’s narrow streets and pavements. Keen to prove my worth as a team member, I volunteered some suggestions of how we might address some of these concerns.

Willie cut me right down to size. “It’s far too early to jump to solutions”.

As always, Willie was ahead of the curve. He prompted me to “unlearn” the rigid philosophy of my planning education and early career: that we are experts and should know everything. He constantly challenged that view, believing that proposals should only emerge after months of patient listening, reflection and discussion. Sometimes a project deadline would be upon us, and he would still be absorbing information and pondering alternative solutions - often in McDonalds in Maryhill, one of his favourite spots for inspiration.

There was never any need to worry. Willie’s proposals were always thoughtful, forward-looking and responsive to environment and community. Fifteen years on, I have just reopened that Dawlish town centre masterplan and looked through Willie’s analysis and proposals; top notch, and just as appropriate now as then. I can only try to live up to that high standard.

Nick Wright

I have known Willie since he was my student on the postgraduate urban design course in Aberdeen in the 70s. He was bright and imaginative then, and we kept in touch when he graduated and went to work as a planner in Coatbridge. We had a common love of Frank Zappa and Alfa Romeos. When he set up WMUD, we were both part of a loose network of community engagement, urban design, local economics, and landscape professionals who formed teams to carry out projects all over the UK.

Although Willie and I would often disagree, we had a common interest in urban design and design briefing, and we both watched in dismay as the early development of that ‘profession’ gradually became just ‘something else that architects do’.

But Willie was an experimenter. We collaborated in early work on applying social network analysis to the street patterns of towns and villages in Scotland and Northern Ireland. We also used community workshops to explore the retention of local wealth and the application of sustainability principles through simple (but not simplistic) models for community use. His later photographic work and the articles he published on his website attest to a lively and expressive mind.

As I write this, it all sounds too serious - we would often corpse over a pun during a conversation - usually held over lunch in the Chip and accompanied by a glass or two. I will always remember the sheer delight on his face when he told me he was to be a father and his last few years with Ines and Maxi were full and happy. His passing will leave a big hole in my personal and professional life.

Drew Mackie

In front of me is a copy of Architecture Without Architects by Bernard Rudofsky, published in 1964 to accompany an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Years ago, Willie urged me to read it and revisiting it now I can see why. He appreciated Rudofsky’s sardonic wit, and he would certainly have sympathised with the introduction - a polemic which pinpoints “the tendency to ascribe to architects – or, for that matter, to all specialists – exceptional insights into problems of living when, in truth, most of them are concerned with problems of business and prestige”.

That could be Willie speaking: he was an exceptionally gifted specialist himself, of course, but he was always attentive to the needs of the communities where he worked, and he was happier listening than talking. Community engagement has become a branch of performance art, and Willie understood the value of a bit of theatre. But his own practice focused on some deceptively simple basic principles: listening carefully, weighing evidence, understanding the place and challenging respectfully. In these ways he put his remarkable talents at the service of the community. Willie’s quiet leadership of the 2016 Talk Prestwick charrette was a masterclass: he gained the trust, confidence and affection of residents and the event left a robust legacy of community activism. He was a remarkable man, and one of a kind.

John Lord

Willie was not a mainstream urban designer of the ‘plansmith’ variety – he neither followed an overtly commercial approach nor sought to impose standardised outputs. As a deeply curious, intellectual designer, he loved getting under the skin of places, their diverse communities and challenges. He was easily bored by any hint of reductive ‘cookie cutter’ solutions.

Working on a Bolton Townscape project with Willie he delighted in telling us about the Mass Observation research of the 1940s, and the earlier 20th century ‘redesigns’ for the de-industrialised town by Thomas Mawson and Gordon Cullen. He loved quirky, eccentric and gritty places and people, with a particular appreciation of avant-garde misfits who broke with convention. On a study trip to Milan, he took me to Lake Como to educate me about Marinetti and futurism; in Bordeaux it was Le Corbusier’s 1920s Cité Frugès that really grabbed his attention and enthusiasm.

Willie viewed towns, neighbourhoods and their designers through a different lens. He saw places as organic works of art, a shifting palimpsest of past and present psychogeography, which we need to respect, understand and curate. Through historical enquiry and innovation, he produced sensitive and subtle plans for improving streets and neighbourhoods, neatly evidenced at Vinicombe Street, which has underpinned the flourishing of Byres Road in Glasgow’s West End.

Kevin Murray

|

|