New Urbanism: Knockroon Revisited

15 Oct 2020

Famed as the Scottish Poundbury a latter day Brigadoon offers a glimpse back through the rose tinted mists of time to how life was lived prior to the arrival of cookie-cutter volume builders. Mark Chalmers pays a visit to find out whether our future lies in the past.

Over the years, Knockroon has provided endless copy for architecture magazines. It owes its existence to an architectural heritage crisis. Its links to the Prince of Wales proved controversial. Its designers were accused of creating a historical pastiche. Knockroon will soon be ten years old and perhaps it’s worth revisiting East Ayrshire to ask whether it achieved its original objectives.

Knockroon was conceived as a new settlement on the edge of Cumnock. It lies close to the former collieries at Killoch and Barony which once employed thousands of men in physically hard but well-paid jobs, but ever since the collieries wound their last coal in the late 1980’s, this part of Scotland has been crying out for investment in regeneration. Sometimes the impetus comes from an unlikely source.

The Marquess of Bute is a major landowner around Cumnock, but in a previous life he was a hero to many young Scots. As Johnny Dumfries, he won the 1988 Le Mans 24 Hours race driving a Jaguar XJR-9, with Jan Lammers and Andy Wallace. Dumfries, alongside Colin McRae and Steve Hislop, were our generation’s motor racing champions – just as Jim Clark and Jackie Stewart were our parents’.

Dumfries raced until 1991 when his father passed away, then he became John Crichton-Stuart, 7th Marquess of Bute. Along with Dumfries House in Ayrshire and Mount Stuart on Bute, he also inherited the financial troubles which go with running landed estates in a modern world. Since his main home was Mount Stuart, built by his great-grandfather, he decided to sell Dumfries House, which had been his grandmother’s home.

The Adam-designed Palladian house still contained most of its original Chippendale furniture, but when it was put-up for auction in 2007 there was an outcry from preservationists. Christies printed a 714 page catalogue and scheduled the first sale for 12th July. But it was the auction that never happened.

At the eleventh hour of the eleventh of July, the Prince of Wales stepped in with a rescue package. A consortium including the Scottish Government, Historic Scotland and The Prince of Wales’s Charitable Foundation saved Dumfries House and its contents “for the nation”. In order to raise the required £45m, the Prince’s Foundation took out a £20m loan with the Bank of Scotland. As part of the deal, 69 acres of land at Knockroon Farm was earmarked for development.

The Prince’s Foundation for the Built Environment took control of the project, leading an Enquiry by Design which explored options for a “sustainable mixed-use development that will serve as a model community for Scotland.” Knockroon was the result, and it owes a good deal to the New Urbanism of Duany Plater-Zyberk which first appeared in Scotland at Scotia Homes’ projects in Aberdeenshire.

The Prince’s Foundation for Building Community later published “Housing Communities: What People Want” which includes a section on Knockroon. Unlike the Aberdeenshire schemes, the Foundation admitted that “The project faced a difficult climate: a very weak national property market, compounded by a lack of consumer confidence and limited mortgage availability. The Cumnock area in particular faced high unemployment levels and low sales values.”

But Knockroon’s promoters were ambitious beyond paying back the loan: “It is hoped and believed that this development will not only create employment and help bring prosperity to the area, but will in the longer term generate profits for donation to charitable causes, once loans associated with the development have been repaid.” Yet Knockroon was always intended as an enabling development, to pay back the cash required to restore and maintain Dumfries House. And that relied on house sales being a success.

Following the Enquiry by Design process, a team including masterplanners at the Prince’s Foundation, architectural designers Ben Pentreath and Lachie Stewart, and local developer Hope Homes were recruited. Their designs drew inspiration from Scottish domestic architecture of the “great era of town building from the late 17th to the mid-19th century”.

How did that work in practice? A register of typologies was drawn up, then the Knockroon Design Code was prepared, consisting of 37 pages of closely-typed text. The level of control is stultifying, even setting out the suggested typeface (Baskerville) and maximum height (8 cm) for the lettering of house names. That’s symptomatic of Knockroon: there is an obsession with minor detail at the expense of a much bigger picture.

In May 2009 the Scottish Government identified Knockroon as one of eleven sustainable exemplar projects. The others include Tornagrain near Inverness (4500 houses on a greenfield site) and An Camas Mòr near Aviemore (1500 houses on a greenfield site), which have similarities with Knockroon: they’re huge developments of newbuild housing on farmland owned by landed estates. A decade on, that greenfield approach doesn’t seem so sustainable.

Another exemplar was Whitecross, whose sad history I wrote about in Urban Realm in 2015. Knockroon raised exactly the same questions as Whitecross: are developers equipped to deliver projects on this scale? Can they address an unmet demand for affordable housing, or the pressure to create jobs in an unemployment blackspot? As a corollary, how can these schemes avoid becoming a dormitory suburb?

Knockroon soon became a high profile target. Architects and commentators concentrated their fire on the mock-traditional design of the housing, but writing in the Scottish Review in 2011, Bill Jamieson discussed the social and economic context. Contrasting nearby Cumnock and Auchinleck with Knockroon, which he characterised as a Scottish Poundbury: “The architect’s drawings of the tree-lined main street show the perfectly formed village pub, the organic greengrocer, the unbust little bank … In no way can this possibly be said to conform to the Ayrshire vernacular: the open-all-hours betting shop; the grim Clansman pub straight out of ‘Still Game’; the bust and boarded-up Woolworths, the off-licence with its heavy metal grilles over the windows and security alarms.

“I doubt if the architects have … factored in the possibility, so remote in idyllic Dorset, of a chronic, draining, crushing shortage of money. Had some of this resource and imagination been put into a facelift of the existing towns nearby where jobs and projects are desperately needed, I might feel less of the burning anger this project has ignited in me.”

Detailed planning permission for the Knockroon masterplan was granted in 2011, and construction of Phase One began immediately. That was to consist of 72 houses, 15 flats and four shop units plus 12 workshops. Looking at the masterplan, 330 houses should have been completed by 2017. To date only 31 houses have been built, and none of those in the last four years.

Martyn McLaughlin, writing in Scotland on Sunday in 2016, noted that the Knockroon site, which was once valued at £15m, had been written down to just £2m. That site value, remember, was the principal security on a £20m loan which the Prince’s Foundation took out with Bank of Scotland.

The masterplan clearly hasn’t progressed as Knockroon’s promoters hoped, hence their economic objective has failed – but have they achieved any of their social aims? Looking through the promotional material produced when Knockroon was launched, one of the stated aims in Hope Homes’ brochure is to achieve: “A resident population mixed in terms of income groups and occupation to help prevent decline.”

But there’s no affordable housing at Knockroon, and the railway station at Auchinleck is a mile away. Those who can afford to live here are car-borne, and just as likely to drive to Glasgow or Ayr as work locally. There’s certainly no evidence of a social mix here, and all the cars are large, shiny and new. Perhaps that’s intentional, because New Urbanism’s detractors claim it amounts to social engineering.

New Urbanism’s well-rehearsed strategy is to attack Modernist planning principles, yet as Jill Grant sums up in her 2006 paper, “The Ironies of New Urbanism”, it “appeals to traditional forms and values while adopting modernist tactics; it supports enhancing the public realm while advancing the private realm; it advocates urban forms while building suburban enclaves; it calls for democratic and participatory communities and an egalitarian social vision while insisting on the need for expert judgement and producing developments for elite customers.”

Was the Enquiry by Design process successful in delivering a sustainable community? The Prince’s Foundation stated, “The EbD held in Cumnock Town Hall, involved hundreds of residents and stakeholders and sought to develop a master plan for a new neighbourhood on the edge of Cumnock, and to set aspirations for its character, its design and its built folk (sic). Those present at the EbD hoped that the new development, to be named Knockroon after the farm on the site, would help to regenerate the nearby towns and reflect their character.”

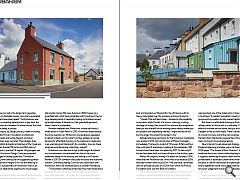

In fact, Knockroon hasn’t delivered on the regeneration, nor has it picked up on the character of East Ayrshire. The development is neither contemporary, nor in the spirit of reinvented Scots architecture which Iain Begg or Crichton Wood might produce. It’s a mash-up of neo-Georgian and pastiche vernacular lifted from Brunskill’s book “Buildings of the Scottish Countryside”. It’s fake heritage of the most superficial kind.

If it was aimed at socially-conservative, Country Life and Scottish Field-reading professional Scots, Knockroon has missed its target by miles. Judging by the property pages of those magazines, their ideal architect would be Robert Lorimer, if he was still in practice. But Lorimer was a clever businessman as well as a deft stylist. He gave his clients what they wanted. Evidently Knockroon hasn’t accomplished that, either.

Yet it could have been very different. Johnny Dumfries is a patron of modern architecture: he commissioned Munkenbeck + Marshall to build a contemporary visitor centre at Mount Stuart. As Kenneth Powell wrote in the Architects Journal in 2001, “Johnny Bute and his family do not live in the great house, much as they love it. ‘I like living in modern houses,’ [Bute] says. ‘Modern architecture is my passion.’” Bute’s father the 6th Marquess was also a proponent of modern architecture. As chairman of the trustees of the Museum of Scotland, he fended off the Prince of Wales’ attacks on Benson & Forsyth’s new building in Edinburgh.

The Butes no doubt knew that there’s a great Scots tradition of lairds creating model villages on their estates: the banker William Cunliffe-Brooks at Glentanar on Deeside, the shipping magnate Donald Currie at Fortingall in Glen Lyon, and the whisky baron John Dewar at Forteviot in Strathearn.

Yet despite their interest in historicism, the Enquiry by Design team clearly weren’t aware of Scots tradition. They claimed to be inspired by Scotland’s planned villages during the Age of Improvement – with gridiron plans, public squares and large civic buildings – but they created something very different. Knockroon was intended to kickstart employment, whereas the Victorian lairds built model villages to provide housing where there was already a demand. It seems that Knockroon happened the wrong way round.

Judged against its stated objectives, Knockroon has failed. The masterplan is only 5% built, and it hasn’t paid back the Dumfries House debt. There’s no social mix here so far, nor any regeneration of the wider area. Knockroon doesn’t reflect its architectural context, nor has it created a sustainable community. As a result, ten years on its wider impact and influence is slight – and while that might cheer up New Urbanism’s critics, it doesn’t settle the fundamental issues of land reform, greenfield development, vested interests, unelected influence and gentrification which Knockroon first stirred up.

Ironically, the thing which may save Knockroon is the new Barony Learning and Enterprise Campus next door – which is unashamedly contemporary, which reflects the values of modern Scotland, and which East Ayrshire Council sunk £68m into. It’s the largest school in Scotland, with 2500 pupils and 300 staff and perhaps, just perhaps, it will create a demand for housing where currently there’s none.

|

|