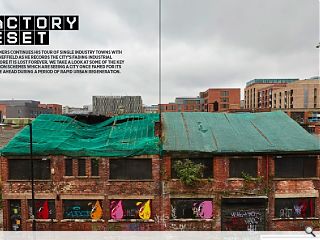

Sheffield: Factory Reset

14 Jan 2020

Mark Chalmers continues his tour of single industry towns with a visit to Sheffield as he records the city’s fading industrial legacy before it is lost forever. We take a look at some of the key regeneration schemes which are seeing a city once famed for its steel forge ahead during a period of rapid urban regeneration.

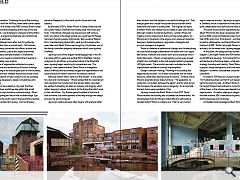

Sheffield is a city in transition. Following the post-War building boom which created the Park Hill Flats, there were further waves of regeneration. The first broke in the 1980’s and as Britain’s steel industry shrank, Meadowhall shopping centre rose on the site of a former rolling mill. Like Braehead in Glasgow and the Metro Centre in Gateshead, a large brownfield site was transformed into an edge-of-town retail park.

A second wave followed soon after, but it’s typified by lightness of touch rather than scorched earth. Old factories in the inner city are being converted into offices, studios and workshops for the creative, cultural and digital economies. Kelham Island is the best example realised in Sheffield to date, although Holbeck in Leeds and the Northern Quarter in Manchester are arguably more mature.

The second wave of regeneration attracted occupiers who value the character and authenticity of historic buildings. Sometimes the building is the only tangible part of their business; architecture is solid and real, whereas their products are virtual and abstract. The footprint of heavy industry can be a positive attribute for software developers, design consultancies and digital branding firms.

Central Sheffield is bounded by a ring road, the River Don and Supertram lines, and three sites within that ambit demonstrate how the city’s transition continues today. Albert Works is home to Jaywing and lies on the southern edge. Eye Witness Works sits to the south-west in the Devonshire Quarter, and will soon be converted into housing. Cannon Brewery stands at Neepsend, to the north, and its future sits in the balance.

By the early 2000’s, Albert Works in Sidney Street was the last cutlery forge in Sheffield, hot forging steel into knives and forks. It had barely changed over the previous half-century, and if you stood in the street outside you could hear its Massey hammers thumping away rhythmically. But Laurence Watson & Co., manufacturing silversmiths, went out of business a few years later, and Albert Works was bought by City Estates, one of the family-controlled property developers which once typified Sheffield.

Jaywing is one of the largest marketing agencies in the UK: it employs 200 in Leeds and another 100 in Sheffield. Having outgrown its old offices, a converted school in the Attercliffe area, Jaywing began searching for somewhere new. The agency’s chief creative director David Wood is evangelistic about Sheffield, and had already bought and regenerated an old cutlery factory at Kelham Island for his previous venture.

Although Albert Works wasn’t on the market – it was zoned for a bar and microbrewery – Wood realised that its industrial grit and a location five minutes from the railway station was ideal. He wanted the building to retain an honesty and integrity which reflect Jaywing’s values, but also to fix the things that didn’t work in their old offices. City Estates grew frustrated at the time it took to evolve, but three-quarters of the way through the design process, the penny dropped.

Jaywing’s creative process often begins with analysis rather than intuition, and that applies to successful buildings, too. That analysis grew into a visual moodboard and document which boiled the brief down to bullet points. The original courtyard at Albert Works was roofed over to create an open plan studio, although it retains its internal elevations. Cellular offices and meeting rooms wrap around, fed by a three-sided gallery. As Wood puts it, the atrium is the engine room where art directors, designers, digital developers, copywriters, strategists and account managers sit together.

Wood is a believer in behavioural change, and did everything he could to encourage collaboration: the desks aren’t too big to lean across, monitors and screens don’t act as obstacles which inhibit discussion. There’s no task lighting, just an even spread of light from northlights in the roof, supplemented by bespoke LED light panels. The acoustics are well-modulated and the displacement ventilation is almost imperceptible.

Design is decision-making. “Nothing in this building has happened by accident. It’s all been considered and we made decisions, rather than leaving things to chance.” Similarly, David Wood is dogmatic about loose furniture – “No pedestals, no waste bins, no dividers between the desks”, and for what did go into the space, the emphasis was on longevity. As an example, the task chairs were supplied by Vitra.

Jaywing moved into Albert Works in April 2017: David Wood reckons the building has succeeded on several levels. He characterised their old offices in Attercliffe as a sad building, whereas Albert Works is a happy one. That’s a very human way to measure success. Jaywing’s recognition has increased in Sheffield, which is important for the brand, but most all, team spirit, collaboration and staff turnover have all improved.

Those are the social and operational aspects of regeneration. Albert Works has also been recognised with architectural awards such as RIBA Local and National prizes, the AJ Workplace of the Year 2018, and a Civic Trust Award – and then our conversation turned to collaboration, and David Wood introduced me to Tim Hubbard of 93ft. While Cartwright Pickard were the developer’s architect, on the tenant side, Jaywing engaged 93ft.

At this point, the design process turned into a giant Venn diagram: Cartwright Pickard and 93ft worked closely together, as did 93ft and Jaywing. Tim Hubbard’s firm covers interior architecture and furniture design, while also offering design strategy, branding and identity. David Wood of Jaywing has a graphic design background, and now works as a brand designer – so there’s considerable crossover between client and consultant.

In addition, 93ft have an unusual model for project delivery. Tim Hubbard pointed out that fit-out designers almost always get to the party too late. At Albert Works it was different; Cartwright Pickard had outlined no more than the regeneration of the street, so the scheme was steered to suit Jaywing’s requirements. As well as playing an integral part in influencing the shell scheme, 93ft’s manufacturing arm produced furniture and the bespoke LED luminaires.

As Hubbard acknowledged, Albert Works was a large, complex project with no hiding places: there’s no drylining, no raised floors and no suspended ceilings. That it was delivered successfully is perhaps due to Sheffield’s ecosystem of suppliers, fabricators and designers. In the same way that David Wood understands which levers to pull as a client, Tim Hubbard is interested in the delivery of projects, and how 93ft can influence that by combining the roles of designer and fabricator.

Almost by accident, my exploration of Sheffield’s old industrial heart then became a study into the courtyard form. Albert Works developed around one court, Eye Witness Works was planned around three, and Cannon Brewery ended up with buildings wrapped around the edges of a kite-shaped site.

Eye Witness Works in Milton Street was occupied from the 1850’s by cutlery manufacturers Taylor’s Eye Witness, who make cutlery, scissors and pocket knives. The name comes from a line from Shakespeare’s Henry IV – “No eye hath seen better” – and the Grade II-listed factory was the last traditional cutlery works left in Sheffield still manufacturing its original products, albeit using modern machinery.

Unusually, the empty building is a by-product of success rather than failure; in 2018 the company expanded into a modern factory and Sheffield City Council produced a development brief for Eye Witness Works. Devonshire Quarter is intended to become another Kelham Island – its industrial heritage harnessed for flats, offices, and studios – and it has attracted interest beyond the Yorkshire border.

Capital & Centric are a Manchester-based developer, and their presence in Sheffield demonstrates a couple of things. Development opportunities still exist in the inner city, and incoming firms have recently broken the grip of the traditional developers who bought up the city’s old cutlery and tool factories 20 or 25 years ago, then sat on them while the market rose.

As Tom Wilmot explained, Eye Witness Works was ideal for Capital & Centric because they aim to go 20% further than a typical developer would to create a project with design integrity. They’re outbid for some development sites, but their approach works best where, as in this case, the city council owns a site and takes design and social issues into account as well as outright land value.

Similar to the industrial potteries of Stoke-on-Trent and workshops in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, Eye Witness Works consists of long, shallow plan dual-aspect rooms lined with workbenches. It’s typical of traditional cutlery workshops in Sheffield, where the Little Mesters worked, and dates back to an era before artificial lighting and long span steel frames.

As Tom Wilmot explained, the large, deep floorplates of Manchester’s cotton mills lend themselves to repetitive flat plans, whereas every apartment at Eye Witness Works will be unique. Architects Shedkm have fitted in 97 loft apartments and townhouses, plus a café-bar. The warren of stairs, bridges and walkways which make Eye Witness Works feel labyrinthine will remain – but each will give onto only one or two apartments. Redevelopment will clear away modern extensions which clutter the courtyards, so these can become lightwells and gardens.

Half a mile away on the other side of the city centre, Cannon Brewery was a Sheffield institution. It featured in two films: “The Full Monty”, and “When Saturday Comes” which was shot there in 1995. The brewery was redeveloped in the 1950’s on a much older site at Neepsend, and continued brewing until 1999, after which it was decommissioned then occupied by scrap men with large hungry dogs. By 2011, all the brewing equipment had been stripped out and it was abandoned.

Since then, it’s become a gallery for the street art which has made Sheffield famous. Artists like Phlegm and Coloquix are less politically-motivated than Banksy, but their work crops up in unexpected places. Coloquix’s female figures with their black cat familiar, just like the Trystero post horn in Thomas Pynchon’s “The Crying of Lot 49”, suddenly appear everywhere you look. Similarly, Phlegm’s “Mausoleum of Giants” installation at Eye Witness Works earlier this year was a clever way to give locals a glimpse of the empty building before its transformation.

The best graffiti features a tangle of words, symbols and graphics which represent fantastical beasts, historical trivia and local knowledge. Tom Wilmot of Capital & Centric suggested that Phlegm’s show at Eye Witness Works is exactly the kind of “meanwhile” use which developers should embrace, to add some social value during regeneration.

However, unlike Albert Works or Eye Witness Works, Cannon Brewery is the wrong kind of industrial heritage: it’s too big and too recent. The courtyard is a space no-one sees, other than a glimpse through the fortified gate on Rutland Road. Yet the brewery has a dynamic character which will soon be lost; whether looking up from the cellars towards the skyline, or down from the brewhouse tower towards the former Rutland Cutlery Works, which was recently converted into a food court.

In August 2015 the City Council approved an application by site owners Hague Plant to demolish and redevelop the brewery. It’s increasingly valuable land, located close to one of the Supertram lines and only a five minute walk from Kelham Island, where 93ft are based, and where George Barnsley’s nearby Cornish Works represents perhaps the last big development opportunity.

After an insight into three projects at different stages of the regeneration cycle, I left Yorkshire with a gnomic piece of street art stuck in my head. Someone had inscribed, “Think out of the tesseract” on a piece of brickwork. The tesseract is a four-dimensional cube where solid reality meets virtual abstraction – something like the new uses being found for Sheffield’s redundant factories.

|

|