Public Commissions: Competitive Edge

10 Jul 2019

From big-ticket public commissions to smaller scale student challenges, competitions have traditionally provided a gateway for practices and individuals to showcase their talents, but is the current system operating in our own best interests?

Open public commissions form a vital component, offering a fast-track to the top for smaller practices and allowing design to flourish in a procurement environment where it all too often of secondary consideration but is the system as it presently stands fit for purpose and if not what can be done about it? A survey by Urban Realm of major public competitions awarded since the turn of the century found that just half were won by indigenous practices with the lion’s share landing outwith the country for major public, university and NHS commissions. While undoubtedly a hugely complex issue we’ve gathered some together various voices from both sides of the argument to establish where public money is flowing and to what degree it is benefitting the indigenous design industry. In doing so it provides a snapshot of the current health of the profession.

Alistair Scott, co-founder, Smith Scott Mullan

When does awareness turn to concern, or realisation turn to paranoia? I admit to a growing awareness of this issue over the years as more commissions get published and awarded. It’s a complex issue, but one of huge importance to our aspirations for Scottish architecture over the foreseeable future. The list of “who designs our buildings” indicated that Scottish based practices are struggling to get a serious share of our major domestic commissions, never mind finding a consistent foothold internationally. We don’t want to be insular and a healthy dose of outside influence is a good thing, but if we want to see a really dynamic architectural scene in Scotland, we need to see a good percentage of our major domestic commissions being designed by Scottish based practices. We have a pool of talented and committed architects in Scotland and I would like to see them influence the world’s thinking, addressing the issues affecting us all. However getting that opportunity needs a stable home base from which to expand. Look at the success of Scandinavian architecture and how it not only promoted its values but has created an export economy for its contractors and product manufacturers. This was achieved through a culture of progressive design linked to a receptive domestic market and government support. I feel Scottish culture is steadily embracing architecture more readily and The Scottish Government is actively promoting this with initiatives like the Place Standard and Town Centre Living. However I feel that many Scottish practices lack the solid economic base and hence the confidence to expand and challenge the larger international players. We are defending our own back yard rather than tackling the world. There are many factors to making this happen, with our old friend procurement still much to the fore. I know many must be tired of us architects going on about it, but when we have a system which favours the large over the small, the safe over the innovative and in which so much effort is wasted, then that does not create the Launchpad we need. So we need to keep pushing to make the process more effective. This is a wide debate with I am sure many viewpoints, but it is one that is well worth having.

Andrew Brown, co-founder Brown+Brown

It’s a subject close to my heart! Not so much on the big-ticket competitions, but in the way it trickles down to other levels of our profession as well. We went for a project recently for a new arts / function building, which we were invited to (privately funded), only to find out at the interview they were asking you to design the building and submit plans and images etc just to be considered. Unfortunately we continue to betray ourselves as a profession by doing such things (we refused by the other submitted firms did not - needless to say we didn’t get it). Our experience of the large public sector competitions is limited, but we see it trickling down to other types of project. What’s more frustrating is when you see the stances of some of the comments on Urban Realm from people that don’t seem to understand if you can’t pay staff, they won’t have architectural work to do. If nobody was willing to do work for free then someone would have to be paid for it, resulting in more paid work in the profession etc. The ‘artist sacrificing financial gain for their craft’ stance gets old. Hopefully Urban Realm can provide a voice on this. The only people who can change it are architects ourselves, which is where some leadership from RIAS would be welcome.

Tony Kettle, co-founder Kettle Collective

The amount of effort practices have to put into competition entries is huge. What other profession has to do that? We donít really enter competitions that are unpaid. We will look at the odds if it’s six staff required and seek payment to cover the costs. Weíve been pretty successful with it but itís not easy and takes a lot of effort. It’s interesting when you see a competition in Scotland how often Scottish architects are on the shortlist. Sometimes the exotic is seen to be anywhere but Scotland and yet when we travel anywhere we see Scotland exporting its design skills and people. That’s something to be proud of. I just wish in Scotland there were times when people looked closer to home. Thereís a great quality of architects in Scotland and if you take them abroad theyíre given the status and priority that they deserve.

David Page, head of architecture at Page/Park

No matter what discipline you operate in, there is a competitive process - whether you are a researcher bidding for grants, a supplier tendering to resource a need, a service seeking to be a provider, for that matter an individual competing for a work position. Architects trying to attract the attention of a potential client through a competitive design process is probably then a reasonable expectation in that broader competitive context. And it is not just now, there has been competition for design ideas for centuries, just as there has been commercial and scientific competition to establish business opportunities and ideas about what makes our world tick. In the academic grant bidding market, that competitive process has been the focus of exacting procedures - you could say it has been to a large extent regulated. In contrast the architectural design competition market has the air of being unregulated, resulting in a bewildering plethora of processes, a kind of design ‘wild west’, big guns coming to town, young kids on the range, pioneering homesteading - some good, but all in all, a bit of a mess. All markets need regulated, it is a fact of life otherwise you get exploitation with all the downsides. What you need is a sheriff, actually a ‘federal’ enforcement agency. In that context then, is that a role for an enhanced ARB, (or even an EU ARB) to categorise the competition market, into ideas, projects, ‘hub like bids’, initiatives etc, with an associated set of procedures and appropriate renumerations, that are determined to be fair, all overseen by a regulatory authority that has teeth.

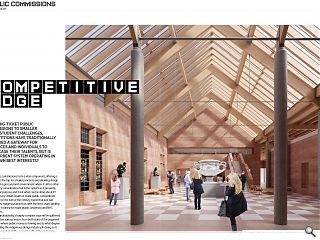

Perth & Kinross Council

Perth and Kinross Council is investing £50 million in culture-led regeneration including the £20M transformation of City Hall. Perth is one of the UK’s architectural gems. Originally a medieval powerhouse it contains some of the best examples of architecture from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries to be found anywhere. So from the outset of the City Hall project we were acutely aware that it will define Perth’s public realm and civic identity for generations to come. We used an international design competition to attract world-class architects but we were clear that the winners had to be ‘practical visionaries’. We used the competition process to test that rigorously ñ affordability was central to our brief. We also asked the public’s views on all five shortlisted designs. The amount of public engagement was undoubtedly increased because of the competition. There was a palpable sense of pride that Perth, whilst a small city, could still have big ambitions. At the same time every pound we spend is public money and every inch of City Hall has to work functionally. We finally appointed Mecanoo from over 70 worldwide expressions of interest and five shortlisted architects, and they were also the clear favourite in the eyes of local residents and businesses. We are delighted with how Mecanoo’s ambition and vision aligns with ours, through their collaborative approach and their understanding of community and civic aspirations.