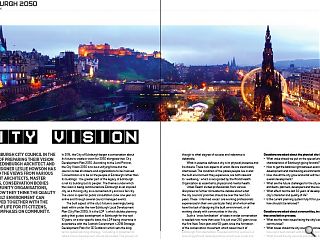

Edinburgh 2050: City Vision

16 Jan 2019

With Edinburgh City Council in the process of preparing their vision 2050 for Edinburgh architect and urban designer Leslie Howson has gathered the views from various prominent architects, master planners, conservation bodies and community organisations. Here they detail how they see the quality of the built environment can be improved together with the quality of life for its citizens, with an emphasis on community.

In 2016, the City of Edinburgh began a conversation about its future to create a vision for 2050 alongside their City Development Plan 2030. According to the Lord Provost, the City Vision 2050 is to be a unifying force and the council invites all citizens and organizations to be involved. Concentration is to be on the people of Edinburgh rather than its buildings ` the greater part of the legacy of Edinburgh is not its building but its people`. The themes under which the vision is being constructed are Edinburgh as an inspired city, as a thriving city, as a connected city and as a fair city. The vision is open for public consultation (now one year on) online and through several council managed events.

The built aspect of the city’s future is seemingly being dealt within under the new Edinburgh Local Development Plan (City Plan 2030). It is the LDP `s which dictate planning policy that guides development in Edinburgh for the next 10 years, on a site-specific basis, the LDP being otherwise in accordance with the Scottish Government`s 2018 Strategic Development Plan (for SE Scotland) which sets the long terms spatial planning strategy, `indicating in broad terms` where future development should be located. The process of producing an LDP seeks to include community consultation, though to what degree of success and relevance is debatable.

What in essence defines a city is its physical presence and its citizens. These two aspects of urban life are inextricably intertwined. The condition of the places people live in and the built environment they experience, are both relevant to `wellbeing,` which is recognized by the World Health Organization as essential to physical and mental health.

Urban Realm invited professionals from various disciplines to further stimulate the debate about what the city councils’ priorities should be over the next 50+ years. These `informed voices` are working professionals experienced in their own particular field, all of whom either have the task of designing the built environment, or of working closely with communities in the city.

Such a `cross fertilisation` of ideas in wider conversation is needed now more than ever. It is just over 250 years since the first New Town plan and 50 years since the formation of the conservation movement which saved much of Edinburgh from demolition. Coupled with this, we live in a time of significant national political unrest over social and community issues, no more so than in Edinburgh.

Questions we asked about the physical city include:

What value should we put on the special urban characteristics of Edinburgh going forward?

How to get the balance right between economic development and maintaining environmental quality?

How should the city grow and what will the next stage of its overall development?

What are the future challenges for the city and how should architects, planners, developers and the council respond?

What effect has the last 50 years of development had on the city’s character and quality of life?

Is the current planning system fully fit for purpose and if not how should it be rehoned?

Questions we asked about communities, inclusiveness and the consultation process;

What are the main issues facing the citiy’s established communities?

What issues should the city council be concentrating on and how can it best connect with its citizens and communities.

What should the city councils priorities be for the next 50+ years?

Malcolm Fraser, architect

Edinburgh is a three-dimensional dynamo of a place, formed by time and violent geology, with its volcanic outcrops scoured by ice sheets and then built on, up, down, through and across with extraordinary vigour and to a set of enlightened and contrasting masterplans whose intellectual clarity and effectiveness still shine. The culture and vigour of its people is intricately linked to this physical place and a clear vision for the city of 2050 requires a new, enlightened masterplan that weaves together place, people and their lives – a new paradigm to deliver the “connected, inspired, fair and thriving city” the City has called-for, that will suit the wellbeing (the health, wealth and happiness) of all future Edinburgh residents, as well as contributing to the enhancement of the local, national and global environment.

The city has outstanding values, which we need to define and respect, springing from that history and the density-with-interwoven-landscape which goes with it. It needs to develop these to build on its strengths by tackling the scourge of inequality that sees some of its citizens cut-off from its riches, recovering the virtues of good social housing and improving the benefits and wealth-spreading capabilities of transport links, whether extended tram, cycle or digital. As with all Scotland a wee bit more local democracy would help, with reinvigorated community councils, as well as support for the good community empowerment initiatives that are the fruit of the Scottish Government’s new legislation, and bold use of the new levers that should come to Local Authorities from the work of the Land Commission and others.

Above all, in this city of clear urban paradigms, from the mediaeval mercat of the Old Town through the rigid rational of the New, it needs to define a future as a city of wellbeing for its citizens.

Robert Huxford, director, Urban Design Group

The late historian John Julius Norwich, chairman of the Venice in Peril Fund, once said that when one considers Venice one must remember that it is not just the individual buildings, the architecture, the monuments; it is the whole thing. It is the sum of its parts. This is true of any town, and particularly true of Edinburgh: a resounding symphony of geology, history, architecture, science, art and enterprise.

Today, the growth of a town or city is very much dependent on private sector developers focussed on maximising the profitable potential of individual sites. But the things that make cities great are ideas and forces that are far bigger that the red-lined site boundary. Edinburgh today is a record of the history and energy of a nation. The Old Town is a fine example of medieval planning and design with its burgage plots, High Street and Mercat Cross, but it is trade and the need for defence of the whole town that were the driving forces. Also evident in Edinburgh is the influence of French culture and architecture following the Auld Alliance and the periodic exiling of Scottish nobility to France returning, when affairs cooled, with fancy French ways.

The New Town is an expression of the ambitions of the Scottish Enlightenment and a desire and need to compete with London. It is a small step from this to Scottish inter-disciplinary generalism, and Sir Patrick Geddes, who was always keen to obtain a broad perspective of how urban societies and economies operated. Part of the legacy he has left in Edinburgh is the Outlook Tower, which provided a camera obscura vista of the city at the top, with descending floors devoted to an understanding (at ever increasing scale) of Scotland, Europe, and finally, the world. Today, cities across the globe look increasingly like clones: expressions of a bland international corporatist style. These forces threaten Edinburgh’s unique character. Geddes wrote that local character is attained only in course of adequate grasp and treatment of the whole environment, and in active sympathy with the essential and characteristic life of the place concerned.”

A great future for Edinburgh will not arise from a vision that goes no further than the profitability of individual development sites. It requires a vision that embraces an understanding of the profitability and welfare of the entire city and the nation which it leads and serves.

Richard Murphy, architect

I empathised with David Chipperfield’s remark at the 2017 Metzstein Discourse that “in Germany they plan; in the UK planning is now called development control, a bit like pest control! It was an observation about how re-active council planning has become instead of pro-active. My experience in Edinburgh is that curiously on the one hand the planning department seems to be very coy about thinking big thoughts; on the other, planners cannot get their fingers out of the fine detail of smaller planning applications.

Its long been my belief that to get a good building you need to get a good architect. Design guides and other leaflets written the much vaunted Architecture Unit and others are a waste of time. And planners have a rotten job taking poor architecture and trying to make it a little bit more palatable. To my mind we should take a leaf out of both the German, and Dutch systems of planning, both of which I’ve had personal experience. In Germany every building, (and indeed urban masterplan), in receipt of public money by law must be the subject of an architectural competition By contrast, the current hubco system bundling up public buildings into lots which are then sold to a contractor who chooses the architect is a catastrophe.

I doubt very much if it ends up being value for money either. Important privately owned sites should also be subject to compulsory competitions. And our two pest control agencies need to have their wings clipped. Historic Environment Scotland should be removed from the planning process entirely and should exist as an information resource about historic buildings giving us a history lesson when we ask for one. They are singularly ill-equipped to pronounce on planning applications. Similarly I think our planning authorities should physically plan as they do in the Netherlands. Aesthetic decisions there are left to the (literally translated) “Beauty committees,” made up of local architects.

Turning to the particularly Edinburgh issues, at the macro scale we should first of all be pleased that Edinburgh is a success story in terms of attracting both jobs and inhabitants (cf Glasgow: I read in the Scotsman once that Edinburgh grows by 10,000 inhabitants per year, exactly the same number by which Glasgow shrinks). Our problems are the problems of success and we need bold physical planning initiatives principally regarding how we can create a denser city, how living and working can be desegregated and how the city can shift much more dramatically towards a public transport system basis and a significant Copenhagen style city centre pedestrianisation. Sadly the proliferation of recent “out-of-town” developments whether they be shopping centres, peripheral low density monocultural housing estates or indeed our main hospital have been counterproductive to these aims. Edinburgh’s success has also had an unfortunate architectural effect of promoting total complacency.

The chief concern, particularly in the City centre and World Heritage Site seems to be to avoid change and discourage development rather than to strive for the very best of 21st century architecture to balance that of the 18th and 19th. Is it a wholly unrealistic idea to imagine that in years to come planes from Barcelona, Copenhagen, Berlin or Paris will be full of tourists coming to hereto see our NEW architecture alongside the historic just as we head to those cities today to do the same?

Petra Biberbach, chief executive, PAS

The Scottish planning system is currently going through a period of reform, with the Planning (Scotland) Bill undergoing scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament. For PAS and our partner organisations, the Bill is an opportunity to encourage a system that is more open, accessible and transparent for everyone.

In particular, I’m pleased to see the Bill putting greater focus on inclusion, enabling greater participation of children and young people, gypsy/travellers and other seldom-heard voices in our communities. We must go beyond listening predominantly to the loudest and most frequent voices if we are to create places that reflect who we are as a society and respond effectively to our changing needs.

We need a more holistic and collaborative system rooted in place. Recent initiatives such as the Place Standard tool (which brings the physical, social and environmental together) have been very useful in changing the way we talk about place. The challenge is now to weave that holistic approach into decision-making across local and national government.

Issues such as social isolation and poor health are just some of many issues that cannot be tackled by individual interventions from individual actors. Planning can play a lead role as facilitator in all the issues that impact on place. If we are serious about place-based approaches, then we need a system that empowers planners (and their counterparts in other services) to work more collaboratively towards common outcomes.

A place-based approach can also help local authorities like Edinburgh engage more effectively with their citizens in conversations about the management and future development of their places. This is particularly important given Scotland’s demographic outlook and rapidly ageing population – the needs of our communities are ever changing.

One of the challenges for the planning system is to address the changing housing needs of older people in our communities and explore alternative models to deliver the homes and facilities that we need.

teven Malone, architect, ADS

There is an increasing policy focus on ageing in Scotland. This is becoming clear in locality plans and the design of services. Ageing is also becoming more important when we decide on the use of our assets or in developing new places.

Addressing ageing is complex. This includes re-thinking how we deliver services and community support and how we can enhance self-directed care. From our perspective it means we need to consider place-based work to shape outcomes that support our ageing population – through sharing resources and supporting action.

Caring Places is such a placed-based approach. Through it we explore the different needs and models of care for older people and communities with the changing opportunities of ‘place’. By placing the needs of the user at the heart of decision making about the provision and investment in services we can create a more caring city.

Alexander Burton, masters student in landscape architecture

Edinburgh is growing quickly as people choose to live in what is an historic compact city. Edinburgh has been built over hundreds of years and we are sitting pretty on the fruits of past generations labour. Planners, architects, landscape architects and developers need to work together in a more holistic way and understand that we all need each other to make a successful project.

The city needs a strong and robust strategic growth plan, especially for transport. Edinburgh has the advantage of being a relatively small and compact city however far too much space is given over to the private car. The car is the least efficient way of moving around a busy compact city and so should be lower down on the list when it comes to decisions on how the city should grow. I don’t think the city is doing anything like enough to protect against air pollution, the ongoing threat of climate change and unstainable urban growth.

Edinburgh has a unique and special character which attracts thousands of visitors from all over the world. However this special character is slowly deteriorating due to poor maintenance and weak planning decisions. Many older parts of Edinburgh are crumbling and the modern buildings that take their place are very uninspiring. There are many contemporary buildings in Edinburgh that are so mundane that they seem to be designed to do the minimum just to get though planning. The public realm and streets in Edinburgh are also generally in a very poor state. The streets are where we spend a lot of our time but they feel neglected, which substantially detracts from the special character of the city.

The planning system needs to put far more emphasis on the quality of the design and the materials used. I think the council need to stand up more to big commercial developers and contractors that build cheap and nasty buildings to make a quick buck. We are leaving a very poor legacy for the future with many new buildings being of such poor quality that they almost seem disposable and will be torn down in 20 years. We need to be brave and design modern but high-quality buildings for the future. The council needs to start saying no to big developers and understand the people will still want to invest in the city event if planning permission is refused.

I have noticed for a while now that the city is slowly deteriorating due to a lack of maintenance and neglect. There are some really special places in Edinburgh but, these are slowly falling apart. Rose Street is a prime example. It is a historic and small-scale street lined with many beautiful historic buildings and is in the heart of the city; however the road surface is appalling. The street could really be something special with lots of small independent retailers, cafes and restaurants. In my opinion the council put far too little emphasis on streets and public spaces and there seems to be very little appreciation of how good quality design can produce that all important sense of wellbeing which is vital if the city wants to remain a vibrant and lively place to live.

Adam Wilkinson, director, Edinburgh World Heritage

The Old and New Town of Edinburgh World Heritage Site will face many challenges in the years to 2050, fundamentally because it is the living heart of a growing capital city.

Thought will be needed about how to sensitively adapt our buildings and spaces to support and not exclude. A great deal more work, building on the experience of the last ten years, will be needed to ensure our existing building stock is thoughtfully adapted to the impacts of climate change.

Increasing pressure on the city centre will increase land values with the danger of not only excluding swathes of the population, but also increasing the pressure to redevelop, and in the process potentially lose much of what is special about the Old and New Towns.

We must avoid the route that London has taken in this respect.

Increasing tourism is a global trend that shows no sign of abating, and we must as a matter of urgency learn how to surf that wave while supporting the communities and cultural authenticity of the city, which are already showing signs of stress.

How we value the city centre World Heritage Site will almost certainly change too, reflecting these changes in society.

The physical infrastructure of the city centre will, by and large, remain – the opportunity is for Edinburgh to lead the way in showing how to reconcile the immense societal changes that can happen across a generation with an extraordinary past.

Rab Bennetts, founding director, Bennetts Associates

Consensus hardly sounds like a compelling vision for a city, but that is the foundation of bold new developments in places like Amsterdam, where a strong design culture has public support.

By contrast, especially in Edinburgh’s historic centre, opinions are as polarised as ever with the former Royal High School being the most prominent battleground, so I question if another way is possible. At present, there is no permanent vehicle for public debate, displays of development proposals or even an exhibition about Edinburgh’s evolution as a great city. Could an architecture centre, accessible to the public, tourists and the architectural/development community alike, establish a deeper understanding of this compelling city and, over time, build a greater confidence about new development?

The idea of an Architecture Centre isn’t new, but Edinburgh doesn’t compare well with cities that have one, like Amsterdam, Hamburg, Milan, Paris and London. In Edinburgh’s case, tourism is an added resource with so many visitors hungry for information about its unique urban form. Beyond the historic core a forum for public debate is just as relevant, with districts from Granton to Craigmillar poised to address the needs of an expanding city.

My own experience suggests that architectural excellence is achieved through transparency, strong ideas, good drawings, logical explanations, thorough analysis of context and meaningful consultations. Any architectural ‘vision’ for Edinburgh in the future is pointless unless there is the will to carry it out, so perhaps the task for the immediate future is to establish the means rather than the end. An architecture centre could go a long way to filling that void.

Conclusion

We need to be sure that those who manage the city truly listen not just to what its citizens need and want, but what their aspirations are. We must also improve community consultation processes within the planning system, in particular by seeking to re-empower its 45 community councils and ensuring that they have the resources, by way of funding and in-built mechanisms, for citizens to exercise that power.

Professionals who design the city environment, the city council who manage it and developers who have the opportunity to build, each have a huge responsibility to create a worthy legacy and not create problems for future generations.

There is clearly a pressing need for a more holistic approach to designing the future city. It is also important that this be on strict urban design lines, using design processes that set a three-dimensional framework as a context for architecture. That will establish an interplay of building spaces that defines its character and becomes `the music of the city’.

It is important to ensure that the City Vision 2050 process embraces not only community and social aspects, as embodied within its four main themes, but the quality of the city’s buildings and spaces for the wellbeing of the city`s citizens old and young, richer and poorer.

It is important that democratic values are not inhibited by an over concentration on economic development. The City Plan 2030 may do this but it has to move away from a piecemeal approach based on land use zoning and site by site proposals to a more strategic vision. The City Plan 2030 should thus be meshed together with City Vision 2050.

How the city grows, how much change will be allowed within Edinburgh’s historic centre and how the city council provides for its citizens will be the true legacy of the next 50 years and this depends on having plans in place for the known, as well as mechanisms ready for the unknown.

|

|