GSA: The Myth of Mackintosh

17 Oct 2018

A second fire at the Glasgow School of Art is the latest affront to the legacy of a genius but mackintosh’s reputation already transcends his work. Here architectural writer Mark Chalmers separates myth from reality behind a creative force whose reputation has only risen with the decline of his work.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh is the only Scots architect whose name everyone knows. He is beloved of Glaswegians, and Glasgow has profited from his legacy, but it’s been a poor custodian of his buildings. Nevertheless, Mackintosh achieved international acclaim and over the decades he’s taken on a mythical status.

Mackintosh belongs to Glasgow, it’s true, but also to Scotland, to the architectural professional and to everyone who loves spindly chairs and watercolour flowers. Today, with his Glasgow School of Art building reduced to ashes for a second time, it’s time to confront the Myth of Mackintosh.

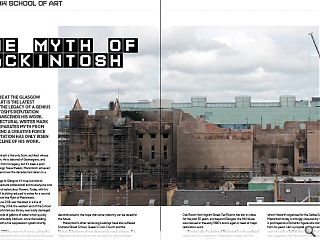

The fire on 15th June 2018 was the latest in a line of misfortunes. On 23rd May 2014, the western end of the School of Art, including its world-famous library, was badly damaged by fire and the thousands of gallons of water which quickly followed. That was particularly bad luck, since the building was due to be fitted with a fire suppression system shortly afterwards.

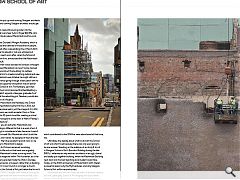

The effects of the 2018 fire were much worse, gutting the entire building when restoration work had reached an advanced stage. At first it looked like the external walls could be saved, but by early July it was clear the wallheads were unstable. Demolition work began in August, and today the shell is being deconstructed in the hope that some masonry can be saved for the future.

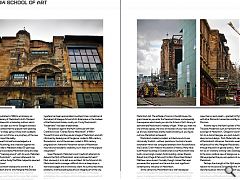

Mackintosh’s other remaining buildings have also suffered. Scotland Street School, Queen’s Cross Church and the Martyr’s School were almost devoured by roads schemes. The Tenement House’s interior was rescued from the bulldozers and transplanted into the Hunterian Gallery. The House for an Art Lover was a stillborn competition entry, although it was eventually built on a different site to serve a different role. The Oak Room from Ingram Street Tea Rooms has lain in crates for the past 50 years, and beyond Glasgow, the Hill House was rescued in the early 1980’s and is again in need of major restoration work.

Paradoxically, the decline of Mackintosh’s work paralleled the ascent of his reputation. Mackintosh’s career was first re-assessed in the 1933 Memorial exhibition, followed two decades later by Thomas Howarth’s book “Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement” and the 1953 exhibition which Howarth organised for the Saltire Society. How we see Mackintosh today is strongly coloured by Howarth’s book: he is portrayed as a Romantic figure who stands above and apart from his peers. He’s a prophet without honour in Scotland, who went into exile in Suffolk then the south of France. Howarth also suggested that Mackintosh could have been as prolific as his contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright, had he been given the breaks.

The next milestone was Robert Macleod’s book “Charles Rennie Mackintosh”, published in 1968 to accompany an exhibition on the centenary of Mackintosh’s birth. Macleod admitted his debt to Howarth’s scholarship, without which Mackintosh might still be seen as a minor Glasgow architect. However, he also pinpointed that the popular myth growing around Mackintosh – “a lonely genius whose work suddenly emerged out of context, out of time, as a prophecy of the new century” – had outstripped the reality.

By 1977, what Howarth himself acknowledged as a Mackintosh cult was flourishing, and a reaction against the Myth had begun. The late Isi Metzstein stated 35 years ago that he wished people would leave Mackintosh alone and stop commercialising and “messing around” with his work. Metzstein labelled the results “Mockintosh” – yet soon afterwards, his former architectural partner Andy MacMillan helped to resurrect the House for an Art Lover!

By the 1980’s, Mackintosh had become a brand. It’s a sad irony that Mackintosh and his wife Margaret MacDonald left Scotland in relative poverty, but today they would be millionaires many times over thanks to the prices their original watercolours and furniture reach at auction. Mackintosh’s favourite motifs – squares, grids and stylised roses – are ubiquitous on t-shirts, jewellery and tea towels. The Mackintosh typeface has been appropriated countless times, sometimes at the behest of Glasgow School of Art Enterprises or the trustees of the Mackintosh Estate, mostly not. If only Mackintosh’s “trademarks” had been trademarked.

The reaction against the Myth continued with Alan Crawford’s book “Charles Rennie Mackintosh” of 1994 – “Howarth’s book and the popular image of Mackintosh are both informed by stereotypes of the genius, rooted in 19th-century Romanticism, and of the pioneer, rooted in 20th-century progressivism. Howarth’s Modernist version of Mackintosh may have lost academic credibility, but it lives on in the popular imagination.”

Given Macleod’s, Metzstein’s and Crawford’s attempts to debunk the Myth of Mackintosh, what continued to fuel it? Most obviously it is his skill as an architect. At the School of Art, Mackintosh had to manage a difficult site on a steep slope, a restricted budget and an ambitious client. He surmounted those problems, and the building became an integral part of the city, combining Scots, Japanese, Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau architecture into a synthesis which anticipates some aspects of Modernism.

Few architects properly understand how to manipulate light, particularly the watery light of Glasgow, as well as Mackintosh did. The enfilade of rooms in the Hill House, the grand reveal as you enter the Tenement House, and especially the sequence which leads you into the School of Art’s library all demonstrate Mackintosh’s mastery of light. When you walk into one of those spaces, the birse on the back of your neck stands up and you stand there silently, head swivelling, as you figure out how Mackintosh achieved it.

Mackintosh created a modern architecture which was intrinsically Scottish – without pastiche or the kind of ersatz baronialism which has consigned attempts from Abbotsford to the Scandic Crown Hotel to the dustbin of history. Many have built Modern buildings in Scotland; few since Mackintosh have built a convincingly modern Scots building. James Shearer, Robert Hurd, Page & Park and Crichton Wood tried; Robert Matthew came closest. Crucially, though, James MacLaren pioneered this approach and he was the most significant contemporary influence on Mackintosh.

At the same time, Mackintosh has a well-developed persona. He created his best-known architectural work when young, in a decade of intense creativity. His departure from Glasgow came at the height of his creative powers, and the hyperbolic curve of his career – from a 25 year old with a louche moustache and floppy neck-tie, to exile wrapped in a dark cape, then an early death – granted his Myth immortality, as with other Romantic heroes like Lord Byron and the singer Jim Morrison.

Another key to the Myth’s power is Mackintosh’s mutability. The early Modernists such as Hermann Muthesius saw him as a pioneer of Modernism. Glasgow’s tourism chiefs enlisted him to re-brand Glasgow as a post-industrial city which was all about art and design. Post-Modernists seized on the plurality of Mackintosh’s influences. Feminists asserted the powerful influence of his wife, Margaret Macdonald, and viewed him through the prism of gender politics. Alan Crawford framed him as an “ordinary working-class Glaswegian”, which appealed to the socio-political view of Glasgow as a workers’ city. We’ve projected the pre-occupations of our own time onto Mackintosh.

Perhaps the strength of the Myth explains the extreme reaction to the second School of Art fire. Within hours, opinions were flying about who to blame. A few suggested on social media that it was somehow Muriel Gray’s fault, that she should stand down and the Board of Governors should resign. Almost immediately, they put forward plans their own to replace the Art School rather than restore it. Funnily enough, well-known Scottish architects suggested that a well-known Scottish architect should get the job; up-and-coming Glasgow architects asserted that an up-and-coming Glasgow architect should get the job…

Given that firemen were still pouring water into the smouldering shell, that was sheer hubris. Roger Billcliffe, who has published several books about Mackintosh and his work, was more measured.

He pointed out that Dundee’s Morgan Academy, which is similarly Grade A-listed and beloved of thousands of people, was successfully rebuilt after a devastating fire in March 2001. Debate about whether to rebuild or not was whisked out of the Twittersphere’s reach soon after, when the School of Art’s Director, Prof. Tom Inns, announced that the Mackintosh building would be rebuilt.

Nonetheless, internet voices decided to conduct a thought experiment. What would Mackintosh do now? Some claimed he wouldn’t simply reconstruct the building: his restless creativity would impel him to create something radical and new. However, even if Mackintosh was still alive, he might still be in exile in the south of France going through a lean patch with no commissions. His great supporter and patron was an earlier Director of Glasgow School of Art, Fra Newbery, yet when the contemporary School commissioned the Reid Building a few years ago, they didn’t appoint a Glasgow graduate. So if Mackintosh was to get the rebuilding job, Newbery would also have to be in a position of influence.

In the absence of Mackintosh and Newbery, the School of Art was laser-scanned following the first fire in 2014, but we can’t claim to have preserved it, just the image of it. In 21st Century fashion, perhaps we could recreate it from a Time Machine back-up of the 3D point cloud file, creating a virtual School of Art like the holograms at the start of Martin Pawley’s book, “Terminal Architecture”.

That doesn’t give you an authentic Mackintosh; but authenticity in a building is different to that in a work of art. A reproduction Van Gogh is considered a fake, because it wasn’t painted by Van Gogh himself. But Mackintosh didn’t build the School of Art with his own hands: he designed it then directed others to construct it. We have excellent records now, so we could rebuild faithfully to Mackintosh’s design.

On one hand, the Art School remained a working building throughout its life and on that basis was arguably more authentic than Mackintosh’s other surviving work. The Tenement Flat is just a stage set within The Hunterian, as is the Tearoom currently being erected inside the V&A in Dundee. The Hill House is preserved as a museum rather than a dwelling house, and the Queen’s Cross Church is no longer a church.

On the other hand, the School of Art just before the fire isn’t as Mackintosh left it in 1909. Changes were made all through its 110 year life, for example when the oriel windows on the Scott Street gable were reconstructed in 1947. As Thomas Howarth notes, the original iron frames were considered too slender and were replaced by bronze in a heavier section. The hot air ducts which contributed to the 2014 fire were abandoned at that time, too.

Ultimately, the debate about what to do with the School of Art was short-lived because there was only ever going to be one answer. Standing on the sidelines of an Andy & Isi crit in Glasgow School of Art’s Bourdon Building during the late 1990’s, I reflected on why we train architects in an ugly, dismal and badly-put together building, when the Mackintosh Building next door was the best teaching aid a student could have. Today, on the 150th anniversary of Mackintosh’s birth, there’s a powerful reason why the Myth endures, and why Glasgow School of Art will be reconstructed.

Mackintosh was the best Scots architect of the past century and the “great grey School of Art hanging over Sauchiehall Street” as Robert Macleod puts it, is his masterpiece. It was a wonderful building and deserves to be recreated, because we have nothing else like it.

|

|