Glasshouses: Green Design

27 Jul 2018

The Front Range glasshouses at Edinburgh’s Royal Botanical Garden have long been hailed as a Hi-tech prototype. Here Mark Chalmers reflects on the wider impact on Modernism presented by these powerful cathedrals to nature.

In 1977, Peter Willis published “New Architecture in Scotland”. It’s a slim paperback illustrated with black-and-white photos which capture the high point of Scottish Modernism, and now serve as a requiem to a generation of architects.

Described as “a survey and celebration of the quality of architectural achievement in Scotland since the early 1960’s,” New Architecture in Scotland features some of the best work of RMJM, Morris & Steedman, Peter Womersley and Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, plus lesser known practices and public sector architects. While the big names are well remembered, those architects who worked for councils and the Ministry of Works are long forgotten.

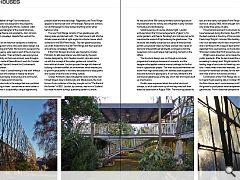

Most of the buildings in Willis’s book are of their time, and some now seem rather dated – yet one stands out, paradoxically because its age is difficult to guess. The Front Range glasshouses at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh celebrated their 50th birthday a few months ago. Their elegance and structural economy come close to realising Bruno Taut’s dream of a completely transparent envelope, and they combine formal experimentation with technology in a way we hadn’t experienced since the Crystal Palace, and wouldn’t see again until the Pompidou Centre.

Leafing through Willis’s book, it’s clear that the sense of unity you experience in the best Modern buildings often got lost behind patterns of brickwork and beton brut: those tropes are the equivalent of today’s barcode facades and rainbow colours. By contrast, the Front Range is another kind of Modernism, part of a different tradition.

Modernism in its widest sense had a social purpose, in the drive to provide decent housing, education and healthcare buildings in the service of the Welfare State. It was an expression of technology, through the development of the steel frame, glass wall and flat roof. It also offered an opportunity for formal experimentation which wasn’t possible using the pattern book approach of Beaux-Arts architecture that dominated well into the 20th Century.

The Front Range’s story began in a conventional way. The Edwardian glasshouses at Inverleith had reached the end of their lives: the structure of the Half-Hardy Temperate House began to rot, and in due course it had to be closed to the public. In 1962, the curator of the gardens, Dr. E.E. Kemp, devised a brief for its replacement.

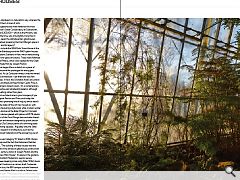

Kemp insisted that the supporting structure should be completely external, in order to maximise incident light and protect it from the corrosive conditions found in plant houses. Although it seems futuristic, the concept of the exo-skeleton was derived from an idea put forward in 1853 by Charles McIntosh, the head gardener at Dalkeith Palace. McIntosh, it turns out, is the godfather of High Tech architecture.

A team of architects was assigned to the project by the Ministry of Public Building and Works, Scotland. Allan Pendreigh was the lead designer of the overall structure, working with George Pearce and assisted by John Johnson. None are well known nowadays, despite their work at the Botanics.

It’s natural, from an art historical viewpoint, to make the designer the starting point of any discussion about design, but the Ministry of Building and Public Works and its successor the Property Services Agency were seen as part of the civil service rather than design studios. Their architects were anonymous and didn’t seek publicity on their own account, even though a good deal has been made of Neave Brown’s work for Camden Council, and Geoffrey Copcutt’s time at the Cumbernauld Development Corporation.

Yet there is also value in concentrating on the work without caring too much about who created it; maybe we should conceive architecture as being “anonymous and communal”, just as Thomas Mann believed art should be.

Perhaps there’s also truth in the adage that every architect has one great building in them – sometimes an entire career is spent working towards it, occasionally a unique opportunity presents itself and the stars align. Regardless, the Front Range appears to be the best work of Pendreigh, Pearce and Johnson, nor do that appear to have tackled anything similar either before or since.

The new Front Range consists of two glasshouses with sloping sides and pitched roofs. The main house is split into five climatic zones and sits at right angles to a shorter house, which connects to the 1854 Palm House. The new glasshouses take up similar footprints to the old Front Range, but their approach and parti are completely different.

If the Front Range’s structure was inspired by Charles McIntosh, its split-level interior was informed by the palm houses designed by John Claudius Loudon, who also came up with the concept of the winter garden and coined the term artificial climate. Loudon pursued the age-old dream of building a climate modifier, an environment which enables you to grow tropical plants in northerly latitudes and to enjoy palms and cycads while the snow is falling outside.

Charles McIntosh’s ideas travelled the world while the man himself stayed close to Edinburgh, and Blackwoods, the most famous Scots publisher of the day, brought out his “The Book of the Garden” in 1853. Loudon, by contrast, was born in Scotland but made his name during a publishing career in London. He was one of the 19th century thinkers behind Agricultural Improvement and his writing was influential in early Victorian horticulture and landscaping.

Glasshouses are, of course, all about light. Loudon enthused about the “immense teguments of glass” in his winter gardens, and Pearce, Pendreigh and Johnson set out to maximise the amount of light entering the glasshouses. The structure was initially conceived as a series of three-pinned portals using tubular steel, but these evolved into a series of diamond-shaped latticed tetrahedra, arranged so that the suspension rods would relieve high bending moments in the rafters.

The structural design was run through a computer programme to analyse stresses and moments, and the designers also applied material science, perhaps for the first time in a glasshouse project. The main structural members are drawn from high tensile steel, with stainless steel suspension rods and aluminium glazing bars. It’s all very different to the commercial glasshouses of the day, which had short spans built up of extrusions.

Doubts were expressed about the radical structural concept, so a full-scale mock-up of two bays was built then tested to destruction in August 1964. The mock-up passed its test, and the newly-completed Front Range later survived the storms of January 1968, which brought winds of 120mph yet only broke three panes of glass.

This empirical approach to structural design could only have happened during the Heroic Age of Modernism. Perhaps the best example is the story of the concrete columns at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax building in Racine. Each nine-inch diameter column has a mushroom-shaped head and is reinforced with a cage of steel reinforcement which departed from usual practice, so the Building Code surveyors in Wisconsin insisted that FLW prove they were sound.

Wright was a showman, so he made the load test into a public spectacle. After he had proved the column was safe by exceeding its design load, Wright insisted the officials continue loading bags of sand onto its flared top, until it was carrying 24 tons – many times more than intended. Johnson Wax was a triumph for reinforced concrete, for the new column concept and most of all for its hubristic architect.

Construction of the Front Range was completed in a rush to meet a Royal opening date in October 1967, but in reality the Palm House wasn’t commissioned until Spring 1968, when the garden’s cycad plants were transplanted into the new glasshouses. From a botanical perspective, the new houses enabled plants to be displayed in a naturalistic way, whereas the Victorians presented them in lines of pots.

The Front Range glasshouses were hailed as the most innovative since Paxton’s Great Conservatory at Chatsworth, and construction cost £263,000 – which as the Ministry was keen to point out at the time, was only slightly more than it would have taken to repair the old Edwardian glasshouses.

How do you go about assessing the Front Range’s place in Scottish Modernism, and its legacy? Its predecessors include the 1834 Palm Stove House at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the 1840’s palm houses at the other Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, which were among the world’s first iron-and-glass structures. These were followed by the original Crystal Palace, which was created for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park by Joseph Paxton.

The Crystal Palace began life as a sketch on a piece of blotting paper and became the prototype for every glass building that followed. As Le Corbusier wrote, it was the herald of a new age of glass architecture – yet there are very few Modernist glasshouses. In fact, the Snowdon Aviary at London Zoo designed by the architectural free-thinker Cedric Price is perhaps the Front Range’s closest cousin. It’s a contemporary which shares the glasshouse’s tetrahedral skeleton, although the aviary is clad in netting rather than glass.

The Front Range’s architects are in good company if you consider them alongside Paxton and Price, and today the glasshouses seem like a promising line of inquiry which wasn’t taken any further. The state-of-the-art has moved on, with commercial growers favouring polytunnels while modern winter gardens, such as the biomes at the Eden Project in Cornwall, consist of diagrids or domes glazed with pillows of PFTE plastic.

The procurement of the Front Range demonstrates there’s a role for public sector architecture designed by public sector architects, even in our 21st Century terms of a shrinking state and public sector funding squeeze. Arguably only the State can support applied research in architecture, such as the introduction of advanced materials and the pioneering use of computer analysis.

The Front Range was Category “A” listed in 2003, thanks to its innovative design and the fact that historians Fletcher and Brown believed, “The building of these houses was the most important event in the annals of glasshouse construction since the nineteenth century works of Joseph Paxton and the construction of the Kew Palm House”. Its place in the gardens, and in the canon of Scottish Modernism, seems secure.

Meantime, I’ve been keeping score using Peter Willis’s book. St Peter’s Seminary at Cardross is a ruinous shell, Cockenzie Power Station is now dust, the IBM campus outside Greenock has become rubble, and Bernat Klein’s studio at Selkirk looks increasingly sorry for itself. These outcomes underline the value of Listing and also the need for quality architectural publishing in Scotland, because one day books like Peter Willis’s will be the only record of Scottish Modernism’s glory days.

|

|