Kirknewton War Room: Cold War

27 Jul 2018

As the Cold War hots up again we dig up the ghost of Kirknewton War Room near Edinburgh, an underground bunker which would have served as a regional seat of government until it became obvious that there could be no protection from a nuclear war. A unique example of utilitarian defence architecture it sadly no longer exists, having been demolished in 2003, but is survived by a sister bunker in Cambridge. Sean Kinnear assesses the fallout emanating from this busted bunker.

Approximately 5 miles Southwest of Edinburgh, just off the B7015 between East Calder and Kirknewton, you will find a typical non-descript industrial yard, nestling behind a razor-sharp palisade fenceline. This site has changed dramatically over the years and shows little trace of its former use as a secret location steeped in Cold War history. Kirknewton Regional War Room, an ex-government bunker, was to have seen civil servants hunker down with a core of emergency staff ready and waiting for a potential nuclear attack from the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, this monolithic, brutalist bunker is no longer with us. Demolished in 2003, a faint grave is now marked by the partial footprint of its concrete foundations.

Like many buildings and structures of this historically unique typology, Kirknewton served a plethora of secret government functions during its lifetime. Following a restructuring of Britain’s defences in the early 1950s, the semi-sunken bunker was built to operate as the Regional War Room for Scotland (region 11 of 12 across mainland Britain). The two-storey modular structure was formed using reinforced, in-situ concrete and boasted external walls and roof up to 5ft thick. The interior layout seems typical of most War Room designs constructed during the Cold War period, with cellular spaces orthogonal in plan being ordered around a central double height map room.

Characteristic of the rapidly developing Atomic Age, these Regional War Rooms soon became redundant as a means of viable defence against nuclear weaponry. By August 1953, the Soviet Union’s first Hydrogen bomb had been detonated acting as a catalyst for bunker architecture and altering the UK’s civil defence plans indefinitely.

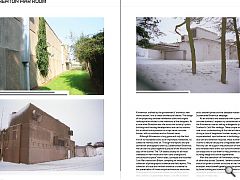

By the 1960’s, Kirknewton had been designated as the new Regional Seat of Government and saw the addition of a significant extension to the original War Room bunker. De-classified drawings uncovered in the National Records of Scotland, show the 1964 two-storey surface level extension having much thinner walls and increased net internal area for an enlarged staff capacity to carry out post-nuclear attack duties. Wayne Cocroft, author of ‘Cold War Monuments: an assessment by the Monuments Protection Programme’, alludes to this change in construction as a reflection of developed civil defence strategies: “The location and design of the buildings implied an acknowledgement that there could be no protection against the blast and heat effects of the H-bomb, and the emphasis was now placed on protection from fallout. This can be seen in the architecture of the purpose-built RSG’s at Cambridge, Nottingham and Kirknewton…they all have thinner walls than the war rooms.”

As the Cold War progressed, attitudes around the nuclear threat and protective measures remained in a state of constant change. When the priority of Kirknewton was reduced, the role of Central Control for Scotland was passed over to the underground bunker at Barnton Quarry in Edinburgh. Final retirement eventually saw all functions of Kirknewton replaced by a state of the art, purpose built Regional Government HQ bunker in Cultybraggan, outside Comrie in Perthshire.

By 1991 the Scottish Home Office had deemed the Kirknewton bunker as “surplus to requirements” and along with the other bunkers at Anstruther and Barnton Quarry, it was placed on the disposal list. What followed was a period of negotiations, tendering and bidding on the open property market. Archive files allude to Kirknewton being a “drain on resources” and prompted the need for a quick sale. This seems to have been expedited by running costs in the region of around £10,000 per month to maintain the facilities.

After being sold to a private developer, the bunker continued a short life post decommission. A range of alternative commercial uses including a storage facility and a nightclub inhabited the ageing carcass of Kirknewton before it finally closed its doors.

The exact time of death is unknown. West Lothian Council had signed the demolition warrant on March 17th, 2003 and with no listed building status to protect this unique piece of Cold War history, the bunker seems to have been eradicated by the following year. Planning history indicates various proposals for the site post-demolition, with the earliest application submitted in 2004 for a new housing development of 15 units with adjoining workshop spaces.

The removal of the bunker was done in line with Scottish planning and building standards legislation. As noted, since the Cold War relic was not a listed or a scheduled monument, it was exempt from listed building consent from Historic Scotland. Also, since the removal was considered permitted development, under class 70 of the General Permitted Development (Scotland) Order 1992, there was no requirement for planning approval before being razed. The only procedures stipulated were prior notification to West Lothian Council and a demolition warrant; which appear to have been completed as required.

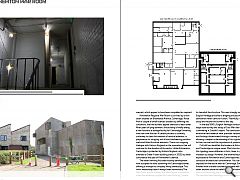

Kirknewton Regional War Room is survived by a twin sister situated on Brooklands Avenue, Cambridge. Aside from a couple of small nuances dictated by differing site conditions, the two bunkers appear identical to each other. After years of lying dormant, the building is finally seeing a new future as a storage facility for Cambridge University who now own the site. A careful process is currently underway to clear the internals of residual asbestos, in preparation for stripping out all non-loadbearing partition walls and fitted furniture elements. There is an ongoing dialogue with Historic England on the renovations that will continue for the duration of the works. Unlike Kirknewton, Cambridge is protected by Historic England, who awarded a Grade II listed building status in 2003; by sheer coincidence the year of Kirknewton’s demise.

The award winning Accordia housing development now occupies the land bordering the Cambridge bunker, offering a strange but uniquely fitting streetscape. This ironic relationship hasn’t always been harmonious The War Room almost suffered the same fate as Kirknewton when the developer applied for Listed Building Consent to demolish the structure. This was strongly opposed by English Heritage and after a lengthy process this attempted demolition never came to fruition. Thankfully, we can visit, study and record the bunker to this day.

In the late 1990’s, English Heritage conducted a large-scale survey and study of Cold War sites in England, culminating in Cocroft’s report. The conclusions of his extensive field research have provided valuable knowledge and findings disseminated through a variety of publications; allowing a deeper understanding of this typology, the risks to their survival and the importance of protection.

CoCroft has identified the bunkers at Kirknewton and Cambridge as unique cases. Most structures of this typology were utilitarian in form, linear in plan and modular by design. However, the external façade treatment expressed at Kirknewton and Cambridge was given conscious architectural consideration. You can see this depicted on the tactile walls at Cambridge. Some areas are finished with a raised concrete aggregate wall texture and other sections show the relief left by the timber formwork used in constructing the in-site concrete structure. De-classified hand drawings of the 1964 extension at Kirknewton, drafted by the government’s ‘architects new works section’, hint at these architectural details. The design of the projecting concrete ventilation cowls and angled roofscape also alludes to the intentions of the designers. At a time when Brutalism was rife across the country’s public buildings and housing developments one can but admire this architectural expression on a top-secret concrete bunker, with no windows and no framed views.

Although Kirknewton is long gone and only the faint hint of its foundations acts as an impromptu headstone, its collective memory lives on. Through the reports and pre-demolition photographs taken by Subterranean Britannica, we can start to piece together a picture of the life and final days of the bunker. The “UK-based society for all those interested in man-made and man-used underground structures and space” have visited, surveyed and recorded Cold War sites across Britain; compiling an extensive collection of photographic evidence and field reports. The collection of visual and written evidence is essential to the preservation of these unique architectural structures. Photographs of Kirknewton bunker can be found within Nick Catford’s ‘Subterranean Britain: Cold War Bunkers’ and a detailed photo archive database hosted on the Subterranea Britannica webpage.

As an architect and researcher with a penchant for concrete bunkers, I express my condolences and perceive the Kirknewton case as setting a dangerous precedent for Scotland’s Cold War heritage. These unique structures are vital to our understanding of the role architecture played during a time of heightened nuclear anxiety, and the unprecedented, rapid advances in technology. Without the due care and attention required, these bunkers will become victims to natural decay and unregulated demolition. Not only can we support the protection of rare examples and venerate them within our built environment, but we can adapt and re-use them to help promote sustainable building design and active regeneration.

With the demolition of Kirknewton, along with a number of other sites across Scotland, I believe consideration should be given to similar structures at risk. Identified key examples would benefit greatly from the protection offered by listed building and scheduled monument status, while demolition proposals could be given greater scrutiny in cases of un-listed sites

|

|