Lost Perthshire: Blasted Past

10 Jul 2017

From Dupplin to Murthly a dispiriting line of vast and ornate Perthshire castles and country houses have been reduced to rubble over the course of the last century, with yet more still at risk of vanishing. In the wake of ‘Perthshire’s Lost Houses’, an exhibition at Perth Art Gallery, Mark Chalmers takes in the imperilled sights of Culdees Castle and Dunalastair house, addressing recurring destructive cycles of history and drawing parallels between the prolific post-war work of Dundonian demolition contractor Charles Brand and Safedem today.

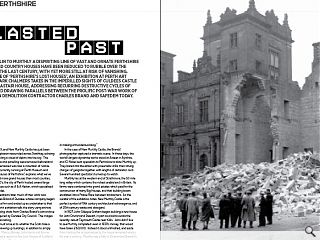

It’s January 1949, and New Murthly Castle has just been dynamited. The explosion resounded across Strathtay, echoing off the hills and sending a cloud of debris into the sky. The fireplaces, staircases and panelling were removed beforehand and sold off; what remained was now a mountain of rubble.

The exhibition currently running at Perth Museum and Art Gallery, “Lost Houses of Perthshire”, explores what we’ve lost. Perthshire had more grand houses than most counties, and in the mid-1800’s, the city of Perth hosted several large architectural practices such as A & A Heiton, which specialised in building stately piles.

Only a few generations later, much of their work was destroyed by Charles Brand of Dundee, whose company began as a house clearance firm and ended up as undertaker to that Gilded Age. The Perth exhibition tells the story using archive photography, including shots from Charles Brand’s own archive which was later acquired by Dundee City Council. The images are sobering but fascinating.

“The question must arise as to whether the Scots take a peculiar delight in blowing up buildings, in addition to simply demolishing them.” Marcus Binney, John Harris and Emma Winnington compiled a report on the Lost Houses of Scotland in 1980, and they felt that, “Scotland seems to have specialised in dynamiting its houses. Scottish sappers and lairds delighted in making a thunderous bang.”

In the case of New Murthly Castle, the Brands’ photographer captured a dramatic scene. In those days, the world’s largest dynamite works stood at Ardeer in Ayrshire, and ICI Nobel sent specialists to Perthshire to blow Murthly up. They bored into the ashlar with pneumatic drills, then strung charges of gelignite together with lengths of detonator cord. Several hundred spectators turned up to watch.

Murthly lies at the western end of Strathmore, the 50 mile long valley which contains the richest arable land in Britain. Its farms were combined into grand estates which paid for the construction of many Big Houses, and that building boom escalated into a Palace Race between landowners. As the curator of the exhibition notes, New Murthly Castle is the perfect symbol of 19th century architectural extravagance, and of 20th century waste and disregard.

In 1827, John Gillespie Graham began building a new house for John Drummond Stewart, in part as a bid to outdo the recently-rebuilt Taymouth Castle near Killin. John didn’t live to see Murthly completed: even in 1830’s money, that would have taken £150,000. Instead it stood unfinished, and aside from hosting the occasional party, the house remained empty for over a century. Murthly was a folly to Drummond Stewart’s vanity.

As John Stirling Maxwell, the founder of the National Trust for Scotland, said in 1937, “This unfinished house, for dignity, proportion and beauty stood quite alone in its day and is still without rival.” Yet the conservation movement was in its infancy then, and the National Trust for Scotland’s founding aim was to protect wild places from development, rather than to save buildings, so it didn’t step in when the decision was reached to demolish Murthly.

Given its sheer bulk, the house presented Charles Brand with a challenge. First, the four flanking towers were pulled off their footings using a hawser attached to a huge Caterpillar tractor, then the central block was blown up by ICI’s men, using four tons of gelignite. The rubble became a quarry, with stone from Murthly used to build houses for the North of Scotland Hydro Board’s staff.

Walter Stahel, a Swiss architect who coined the expression Cradle to Cradle, was one of the first to put forward the concept of a Circular Economy which encourages us to reuse, repair and recycle. His work goes to prove that there’s scope for architectural thinking everywhere – yet the recycling of building materials began long ago, perhaps in the Dark Ages when medieval masons liberated stone from Roman ruins.

Stahel’s ideas have been seized upon in recent years, but their application is patchy. The closure and redevelopment of hospitals, particularly Victorian insane asylums, was triggered by the Care in the Community Act and reached a peak at the turn of the 21st century. Some were lost to the hydraulic pincers of the demolition man’s full-slew machine, but many have been converted into flats.

The dismantling of railway infrastructure in the 1960’s, and the conversion of many into bike paths, began with the Beeching “Axe” – although some closures were reversed with the reopening of the Airdrie-Bathgate route and part of the Waverley Line. Similarly, waves of schools, hospitals and tower blocks were built during the post-war boom, then brought down half a century later by Charles Brand’s spiritual heirs, Safedem of Dundee. The Red Road Flats are an infamous example of their work.

Church construction went in spates: a boom after the Reformation, another after the Great Disruption, and a smaller peak after World War Two. Since then, the slow retreat of organised religion means that more church buildings are now used for other purposes than remain as places of worship. Churches were fortunate, in that many were listed.

By contrast, the destruction of mansion houses and castles after the Second World War came about before they had any statutory protection. Victorian architecture was deeply unfashionable by the 1940’s, and in his book “Scotland’s Lost Houses”, Ian Gow reckoned that over 200 major houses have been lost in Scotland since 1945, including vast 19th century mansions such as Perthshire’s Abercairney and Millearne.

Marcus Binney put the figure even higher, estimating that Scotland lost more than 450 houses of “architectural pretension” between 1900 and 1980, with over 60 of those in Perthshire alone. Duncrub Park, a Baronial-Gothic mongrel, was demolished in 1950, the year after Murthly, and Dupplin Castle was pulled down in 1967. Dupplin was a Tudor folly, designed by William Burn and known today only in picture postcards.

The late Charles McKean, Professor of Scottish Architectural History at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, said: “We may live in a different world from the one Gow shows in his book, but houses are still being demolished and many are now marooned by the land-holding laws. It’s not a battle won. When these beautiful big houses were built all those years ago they were occupied by complete communities. That is not the case now.”

The Lost Houses exhibition presents tableaux of be-whiskered shooting parties, and a matriarch reposed on a settee like Grandma in Carl Giles’ cartoons. If they appear stern and unforgiving, perhaps they realised the era of gracious living was coming to an end. Many baronial houses, like Scone Palace and Glamis Castle, have become heritage attractions in order to survive.

What the exhibition doesn’t explore is the shape of the conservation movement in Scotland while all this destruction was going on. Perhaps the first milestone was Thomas Howarth’s book about Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It was published in 1952, which was early enough to contribute towards saving the Tenement Flat and Scotland Street School from Glasgow’s motorway planners.

Henry Russell Hitchcock’s plea to save Caledonia Road Church was published in 1965 – too late, because many of Greek Thomson’s Glasgow buildings were already rubble. Today the church is still a shell, and the Egyptian Halls await salvation. Robert Matthew was more successful: in 1970 he spearheaded the Conservation of Georgian Edinburgh Conference, which is credited with protecting the New Town from comprehensive redevelopment.

Arguably it took until 1974, with the Destruction of the Country House exhibition at the V&A in London, and the founding of SAVE Britain’s Heritage the following year, to bring Lost Houses to the public’s attention. However, neither books, exhibitions nor pressure groups managed to solve the underlying financial issues.

In the post-War years, death duties led to much destruction: today the tax system is still loaded against historic buildings. Restoration work is VAT-rated, whereas newbuild work isn’t. The 90% business rate relief on unused buildings was recently abolished. Those measures, taken together, tacitly encourage the demolition of disused buildings.

Although Perthshire’s more recent lost houses aren’t included in the exhibition, Ardoch House at Braco was pulled down in the 1980’s, Ardargie House at Forgandenny was demolished in the 1990’s and Achalader House near Blairgowrie was lost as recently as 2012. So the cycle of construct-and-demolish continues, unabated.

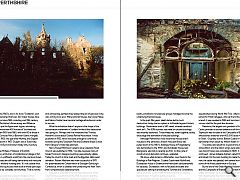

We know what remains a little better, now, thank to the Buildings at Risk Register. Culdees Castle near Muthill and Dunalastair House in Strathtummel have both sat abandoned for decades. Dunalastair, with its fairytale silhouette and spectacular setting overlooking the Tummel and Schiehallion, was built in 1852 by the Perth architectural firm of Andrew Heiton & Son. It lived for exactly a century.

Dunalastair was later bought by the Tennents brewing family, then the chairman of the Caledonian Railway, and finally requisitioned during World War Two. Afterwards it became a school for Polish refugees, who set fire to the dining room. As a result, it was vacated in 1952 and has stood as an increasingly ruinous shell for the past few decades.

Meantime, the largest and grandest of them all, Taymouth Castle, provides a counter-balance to all the destruction. Taymouth was the seat of the Campbells of Breadalbane, whose lands stretched over 400,000 acres from Perthshire to Oban. Originally built as Balloch Castle in the 1500’s, it was demolished then rebuilt by William Adam in 1733.

The castle was rebuilt for a second time by Archibald and James Elliot: only the Adam wings were retained, and the new Grand Tower was completed in 1809. In 1842, the cycle continued. James Gillespie Graham rebuilt the east wing again, and linked it to the main building to create the Banner Hall. By now, the castle was palatial, with several hundred rooms and some of the finest plasterwork in Europe.

By the end of the Great War, the Victorian age had faded and the Campbells of Breadalbane had lost their fortune. The estate was broken up to settle enormous gambling debts, a fact underlined by the mirror-inlaid ceiling in a turret room, reputedly used by Lady Campbell to cheat at cards.

Taymouth Castle was sold in 1920 to a consortium which converted it into a hotel, installing Art Deco lifts and turning the deer park into a golf course. Like Dunalastair, Taymouth was requisitioned in 1939, in this case as a war hospital. It later became a resettlement centre for Polish refugees, then a Civil Defence School, and finally a school for the children of American expatriates.

By the late 1970’s Taymouth had fallen into disuse, except for occasional dinner parties – a fate it shared with Murthly. The castle’s owners spent the 1990’s trying to sell the estate: Madonna was apparently interested, until she discovered she wouldn’t be allowed to close the golf course to the public.

Finally Taymouth was bought with the intention of turning it into Europe’s first “seven-star” hotel. Restoration work started in 2002, when McKenzie Strickland Architects began to undo decades of unsympathetic alterations, and work has continued through a couple of changes of ownership. Intricate mouldings have been recreated, and gentle cleaning of the Chinese Gallery’s ceiling revealed its original colours.

Taymouth has been saved; still, the Lost Houses are heritage, too. Those ghosts of progress, which can’t be redeveloped, restored or converted, emphasise the transience of people and their vanities. Sometimes Lost Houses can’t be saved; sometimes we just have to accept that architecture goes up in smoke.

|

|

Read next: Wavegarden: Swell Design

Read previous: Housing Crisis: Personality Built

Back to July 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.