Sigurd Lewerentz: Personality Cult

11 Jan 2017

Photo-journalist Mark Chalmers journeys to Denmark and Sweden to investigate parallels between local hero Sigurd Lewerentz and the cult of Gillespie Kidd and Coia here at home to see at first hand the powerful effect a prolific architect can have on a small country.

St. Petri Kyrka is 50 years old. It’s a brick kirk in a small town called Klippan, which lies in the Skåne region of Sweden. Although Klippan is a backwater, St. Petri has become world-famous. It was designed by Sigurd Lewerentz, around whom a cult has grown up – yet it could easily have been so different.The fact we know about Lewerentz is partly thanks to the exhibition which Alvin Boyarsky organised at the Architectural Association in 1989, but mainly due to the Swedish architect Janne Ahlin. His book, Sigurd Lewerentz, Arkitekt was translated into English in 1988 and is still the definitive source on the architect’s life and work.

Over the course of the next few years, Lewerentz was gradually assumed into the canon – the “other tradition” of Modernism, among the awkward ones like the Smithsons, Pietila, Giancarlo de Carlo. The making of the myth around Lewerentz is an interesting process which proves that, ultimately, we have no control over reputations.

The resurrection of Lewerentz’s career was unexpected. He re-emerged in the Sixties to build a handful of startling buildings which explore architecture’s fundamentals. Sweden had forgotten about him by then: he was a man of the distant past, born in 1885, his notable work created in the early decades of the 20th century.

Lewerentz grew up in Lund and studied at Chalmers Technical University in Gothenburg, which was founded by the son a Scots merchant. Early in his career, he worked with Gunnar Asplund on a series of commissions including the Eastern Cemetery in Malmö, but after adding the St. Knut & St. Gertrude chapels to the cemetery in 1943, work appeared to dry up.

For years afterwards, Lewerentz concentrated on producing furniture and architectural hardware to his own designs: he was the Knud Holscher of his day, and his “Idesta” range may have given Holscher the idea for “D-Line”. So the 1955 commission to build a new kirk, St. Mark’s at Björkhagen in Stockholm, evidently came as a surprise to everyone other than Lewerentz himself. It was his first major building in over a decade.

Even as they briefed him, the kirk session was concerned that the architect’s age might militate against him completing the project – but when it opened in 1960, they realised that Lewerentz had achieved something unique.

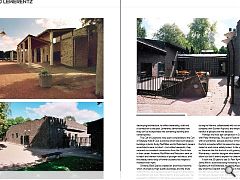

Following on from St Mark’s, Lewerentz was commissioned to design the St. Petri Kyrka (Church of St. Peter) at Klippan in 1962, at the age of 77. He drew upon a lifetime – nearly six decades of practice by that point – to build a profound piece of architecture. By then, he was a formidable old man who worked from a studio of black and silver in Lund, another small town in provincial Sweden.

I’m certain that no-one else, not even a younger Lewerentz, could have designed St. Petri. While the St. Knut & St. Gertrude chapels in Malmö are understated and uplifting, St. Mark’s and especially St. Petri are powerful, primitive and timeless. At Klippan, Lewerentz seems to prove that it takes a lifetime to condense what’s worthwhile then translate it into architecture.

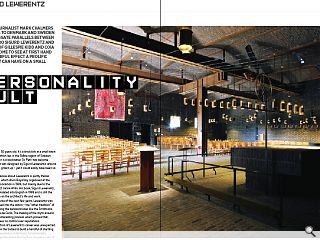

St. Petri was consecrated exactly fifty years ago, on 27 November 1966, and remains much as the architect intended. When you walk into the sanctuary for the first time, the birse on the back of your neck stands up. At the kirk’s consecration, Bishop Martin Lindström declared that, “a renowned architect has with all his being built here a hallowed room of majestic weight,” and Lewerentz certainly achieved the gravity of a cathedral in a compact package.

Of course, the medieval cathedral builders had the advantage that ordinary folk in the Middle Ages were easy to impress: the grandeur of a cathedral was so overwhelming and so far out of their everyday experience. By contrast, Lewerentz’s churches are modest in scale, built from humble materials, and tucked away in small towns and suburbs.

In the moments when you have St. Petri to yourself, you’re conscious of the burning wicks of wax tapers, the enveloping darkness, and the steady drip of a font which demarks the silence. Beyond them wrap a series of strangely-angled vaults, a sloping floor and slots in the walls and roof which beams of light spear through. St. Petri taps into ancient places, perhaps the caves in which Christian saints first took refuge when they reached the West from the Holy Land.

Most of all there is the burnt-dry air, which smells and tastes like the inside of a brick kiln. I know that smell will stay with me and instantly take me back to Klippan – just as the smell of hot electrics and Ferodo dust transports you to the Tube lines under London. St. Petri’s atmosphere is a major factor in the cult which has grown around Lewerentz since his death in 1975.

Another is the fact that Lewerentz was a radical thinker. He questioned what the wall does, and what a window is. Ahlin recounts that he wrestled with these fundamentals in private, in the wee hours of the morning. It’s difficult to know where the solutions sprang from, because Lewerentz was rarely forthcoming about his work, although he did mention Persian brickwork as a source of inspiration.

At St. Petri, Lewerentz concluded that you can build a floor, walls and roof from the same material – purple-brown clinker bricks from Helsingborg Ångtegelbruk – and he decided that you can form openings simply by leaving a hole, spanned by bricks laced together with rebar. The windows are no more than double-glazed units sealed to the brickwork: the glass doesn’t need a frame.

The vaulted roof is carried on a “T”-shaped column, built up from rolled sections of CorTen steel which hint at a massive cruciform. Even the faucet in the washroom is just copper pipe formed into a spout, the taps are brass valves with cross-heads. St. Petri is architecture stripped down to its essentials – but that doesn’t mean a reductive Minimalism.

Lewerentz straddled the eras of Neo-Classicism, Arts & Crafts and Modernism. He came from the generation of Corb, Mies and Gropius, all of whom worked for Peter Behrens during the era of the Deutscher Werkbund. Lewerentz also worked for a time in a Werkbund-influenced practice in Munich, and he carried the things he learned there through his career: a love of craftsmanship and an insistence on total design. Like the other Modernist masters, he designed the building and everything which went inside.

The construction process of the kirks at St Mark’s and St. Petri has also taken on a mythical status thanks to the way in which Lewerentz built. He insisted that no brick should be cut, and he never rejected a brick which others would have considered flawed. In fact, he consciously selected seconds and over-burnts for the kirk: perhaps he felt that the imperfect bricks were a metaphor for humanity’s fall from grace.

Lewerentz spent endless days on site, discussing and directing the works – his method harks back to the Masters of Works who oversaw the construction of the great cathedrals. Perhaps only the Church could indulge an architect like this, but St. Petri would never have been realised without the partnership between Lewerentz and his tradesmen.

Sometimes work proceeded by experiment, trial and error and intuition. Best known is the story of the exasperated metalworker at St Mark’s who asked Lewerentz, “If I can’t do it this way, then how shall I do it?” The architect’s answer was, “That I don’t know. All I know is that you are not going to do it the way you normally do.” Even then, the workmen realised they were engaged in something unique.

So, the machinery of myth drew upon the man, his methods, and the finished work. But there are outside factors, too. Today’s practices are measured by their turnover, how many schemes they have on their books, and how many awards the projects win afterwards. Their reputations are reinforced by books, exhibitions and magazine articles. There’s a beaten path which Reiach & Hall, Page & Park, Richard Murphy and many others follow towards recognition and success.

It was no different during Lewerentz’s lifetime. His contemporaries won competitions and accolades while his own career lay dormant. They saw their work published in magazines just like Urban Realm, hoping the articles would help to establish a reputation and offer a critical view of their work. By contrast, Lewerentz was inscrutable: over the last few decades of his career he didn’t lecture, publish or teach.

That only served to fuel our curiosity. The myths around Lewerentz grew after his death, and over the past few years, he’s become an inspiration to a new generation of architects. For those who believe the digital era is destroying architecture, he offers materiality, craft and a connection to the past. Lewerentz demonstrates how they can be incorporated into something startling and contemporary.

The Cult of Lewerentz may seem comparable to the Cult of Gillespie Kidd & Coia: a practice which also built religious buildings in brick. Andy MacMillan and Isi Metzstein’s careers as architects were cut short – but unlike Lewerentz, they received no comeback commission from the Church late in their career. However, MacMillan and Metzstein went on to teach and mentor hundreds of younger architects, and the steady name-drop of former students has helped to maintain their myth.

Similarly, Basil Spence created an enormous machine which churned out high quality buildings, and the brute maths of how many people passed through his office led to an exhibition and book “Basil’s Bairns” a few years ago. Yet Lewerentz is different in that sense, too, because he stood alone. He exercised very little influence over other architects during his lifetime, collaborated with no-one after he parted company with Gunnar Asplund, and employed only a handful of people over the decades.

Perhaps the most apt comparison in Scottish terms is with Peter Womersley. This year’s Festival of Architecture, with an exhibition, lectures and tour of his buildings marks the first concerted effort to assess his reputation and make his work more widely known. In the process of doing so, there are the first hints of a cult growing up around Womersley – another designer who developed his own idiom but didn’t seek to explain his creativity.

It took me 20 years to see St. Petri Kyrka, from reading Janne Ahlin’s book and being moved by its final chapter, The Epiphany of the Bindweed, to visiting Klippan on a summer day when the Swedish railways were in meltdown. Perhaps the wait was justified. I don’t think I would have appreciated St. Petri as a student, and I still don’t fully understand what Lewerentz achieved at Klippan, but I now have an inkling how cults are created.

|

|

Read next: Architecture in Crisis: Rotten Burghs

Read previous: The Monzie: Dereliction Duty

Back to January 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.