Glasgow Interiors

15 Jan 2015

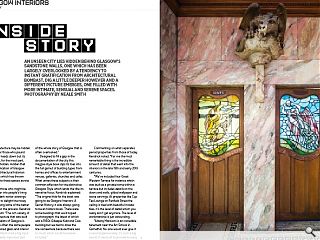

An unseen city lies hidden behind Glasgow’s sandstone walls, one which has been largely overlooked by a tendency to instant gratification from architectural bombast. Dig a little deeper however and a different picture emerges, one filled with more intimate, sensual and serene spaces. Photography by Neale Smith

Glasgow’s architecture may be hidden in plain sight for those who pound its streets with heads down but its interior spaces, for the most part, remain simply hidden. Hidden that is until the publication of Glasgow Interiors by architectural historian Helen Kendrick which has thrown open the door to these spaces across its 161 pages.Penned forthose who might be tempted to peer into people’s living rooms during dark winter evenings it is something to delight the nosey whilst cataloguing some of the better known spaces in the process. Kendrick told Urban Realm: “The rich variety of domestic architecture that was built for the industrialists of Glasgow is remarkable. It’s often the same people that did the stained glass and interior

design and architects had a big input as well. It’s anreally important part of the whole story of Glasgow that is often overlooked.”

Designed to fill a gap in the documentation of the city this magpie-style book dips its toes into the full gamut of building types from homes and offices to entertainment venues, galleries, churches and cafes. What unites these subjects is their common affection for the distinctive Glasgow Style which lends the title its narrative focus. Kendrick explained: “The original title for the book was going to be Glasgow Interiors: A Secret History, it was always going to be an historic book. There were some buildings that we’d hoped to photograph, the latest of which was a 1950s Gillespie Kidd and Coia building but we had to draw the line somewhere because there was so much which could have been included.”

Commenting on what separates period properties from those of today Kendrick noted: “For me the most remarkable thing is the incredible amount of detail that went into the interiors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“We’ve included four Great Western Terrace for instance which was built as a private home within a terrace but includes details on the doors and walls, gilded wallpaper and stone carvings. At properties like Cup Tea Lounge on Renfield Street the ceiling is tiled with beautiful mosaic tiles, it’s the level of detail which you really don’t get anymore. The level of workmanship is just astounding.

“Albany Mansions is an incredible tenement near the Art School in Garnethill. No-one would ever give it a second glance really; it’s such a big secret. It was built to provide housing for art]]ists so it’s got this wonderful double height lounge space. The detailing in the close is fantastic with stained glass and tiles.”

Adding a photographer’s perspective to the mix Neale Smith, whose images illustrate the bulk of the book, told Urban Realm: “Glasgow Interiors was shot over the space of six months, there was a lot of pressure with regards to the time frame and shooting interiors using my preferred methods is not a quick process.”

Working in gloomy halls and corridors presented particular challenges in respect of harnessing light, something which forced Smith to assemble a hi-tech armoury to fully reveal the interiors as their designers intended. “Some of the spaces represented a real challenge on the technical side, which for me is the best situation,” noted Smith. “This is where I get to learn and really push what I’m doing, especially with regards to lighting. I like to use supplementary strobe lighting, when I’m shooting interiors, it takes care of a whole host of technical problems, and shortfalls of digital cameras which allows me to get closer to nailing it in less shots. This is important as I then selectively light separate parts of the entire scene and later composite these in post-production. This involves a lot of work and a lot of extra shots.

“Due to their nature digital cameras are at capturing what the human eye sees and there are still big technical issues to be dealt with. The dynamic range even on the high end pro spec cameras isn’t good enough to capture certain scenes in one shot, and this is where architectural photography differs a lot from other types of photography. You have to know what you’re doing and how to solve problems on location and then potentially later in post-production.”

Of course to properly photograph a building it first has to exist, an acute problem in Glasgow which has borne the brunt of maniacal redevelopment in the 1970s which erased whole districts of the city. This only serves to make that which survives all the more precious and, as Kendrick pointed out, that is often rather more than meets the eye. “Although there have been many losses there’s a greater proportion of historic glass surviving in Glasgow than any other city in Britain.

“When you walk through suburbs like the West End and Pollokshields you can see this amazing Glasgow Style glass in the tenements, launderettes and old cafes, it really gives the city a huge amount of its character.”

Nevertheless the opulent townhouses of former industrialists and middle class suburban haunts are a far cry from the slum conditions that most called home during this era but Kendrick points out that attention to detail was often lavished on properties whose owners had little. “We couldn’t miss out on buildings like the city chambers but we’ve included the tenements and a traditional wally close. These weren’t built for the city elite by any means but were built for the ordinary population.”

When revering the past it is easy to fall into the trap of slavishly protecting it at all costs, an accusation often levelled at Edinburgh if not its west coast counterpart, but Kendrick acknowledges the importance of working with these spaces to adapt them for modern needs and uses. The Victorians and Edwardians may no longer be with us but their city lives on.

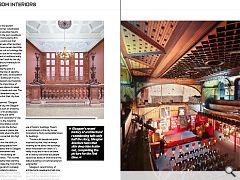

Kendrick observed: “Glasgow is such a creative city, the Glasgow school of Art has such an enduring impact in terms of its architecture and design.” Picking out some recent examples of successful re-use Kendrick points to the industrial space under Central Station which was transformed into the Arches entertainment venue or places like Maryhill Burgh Halls where the attic space has been converted into high quality office space. .

But have we lost the ability to create such amazing spaces from scratch? It’s fantastic that in Glasgow there is a real commitment and desire to re-use the building we have,” notes Kendrick. “For me that for me is much better than starting from scratch to make the most of the design knowledge which is already here. Historic Scotland is doing a wonderful job with initiatives like the Glasgow City Heritage Trust. Glasgow City Council has a strong agenda for celebrating and supporting our use of historic buildings. There’s a commitment in this city to use innovation to find a sustainable future for buildings.

“I know a lot people are quite surprised by that, they’re always moaning at me about the buildings which have been torn down. It’s really tricky and it has to be done on a case by case basis but people need to be aware of what kind of the state a building is in before being too judgmental.”

Glasgow’s recent history of architectural reawakening tells only half the story, Glasgow Inter

|

|

Read next: Design Pop-Up

Read previous: Lighting Design

Back to January 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.