Freiburg - neighbourhood Watch

16 Jul 2014

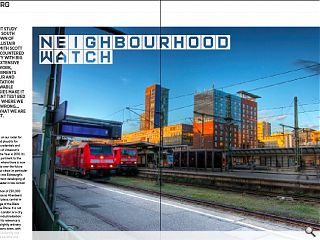

On a recent study trip to the south German town of Freiburg Alistair Scott of Smith Scott Mullan encountered a small city with big ideas. Its extensive cycle network, bold experiments with colour and experimentation with renewable technologies make it an excellent test bed to look at where we are going wrong... But also what we are doing right.

Freiburg has been on our radar for years. It has earned plaudits for its environmental credentials and was The Academy of Urbanism’s European City of the Year in 2010. Its lessons are highly pertinent to the Scottish situation, where there is now a vociferous debate over the future development of our cities (in particular the encroachment into Edinburgh’s greenbelt) and a vision developing of our country as a leader in low carbon technologies.With a population of 230,000 (about the same size as Aberdeen) Freiburg is a good place, central in Europe, on the edge of the Black Forest and near the Rhine. It is not a world centre like London or a city responding to de-industrialisation like Barcelona and its relevance is magnified by this slightly ordinary situation. It is a historic town, with a Cathedral and a University and it could easily have become one of these complacent small cities which are beautiful but tend to resist change (any Scottish suggestions for that accolade?). But it didn’t do that, it turned itself into a model of sustainability with an enviable lifestyle and an environmental industry which employs 2000 people in the solar sector alone. It has no oil, no sub-sea power, little wind power and its success is not based on big hits but on community consensus and well considered public policy, consistently applied over a long period of time.

The citizens seem to have a good life, cycling to work, drinking beer in pavement cafes and living in an environment where kids can play close to their own homes and walk to school. Electricity is generated from solar power and district CHP plants and city making a well-accepted process. The new neighbourhood of Vauban is a European exemplar of regeneration and attracts people like us to study it and boost the local economy.

Freiburg has also gone for solar power in a very big way. One of the warmest cities in Germany, it has more than 1800 hours of sunshine a year, which is more than Scotland but not outstanding in a global sense. This is achieved through concentrations of panels on large buildings such as stadia and supermarkets which contrasts with our much more piecemeal approach.

The current story began with a visit from the Royal Air Force in 1944 in which 80% of the city centre was destroyed. The Cathedral was spared (as miraculously often happens) and they chose to rebuild the city centre to the existing medieval street pattern. There are indeed the anomalies of pastiche, brutalist buildings capped with traditional pan tile roofs and old buildings which are almost new, but the result is a sense of place which eluded most post war redevelopment.

But our real interest was in the more recent developments. Like many German cities they adopted a “finger principle” of expansion, building from the existing, along transport routes and generally supporting the existing city rather than challenging it. This was founded on a concept of neighbourhoods and was carried out with a process of civic planning to provide the infrastructure of transport and public facilities at an early stage.

Vauban – Greenest Neighbourhood in Europe?

Lying on the edge of the city, this new neighbourhood of 5000 inhabitants covers a land area of 38 hectares on a former French military base. Working with a protest group with strong environmental credentials, the city authorities acquired the land in the 1990s, formed a task group and initiated the project.

The first thing that you see when arriving in Vauban is the much photographed solar housing project which wears its solar credentials on its sleeve and just about every other part of the body. Across from it is the much lower key timber and planting clad eco-hotel (what a great thing to have in a regeneration area) and the 19th century military buildings where it all started. Vauban is a recognisably “special” place with a strong feeling of community ethos which its residents support and a successful blend of, planning, architecture, environmental, social and political agendas.

The layout is extremely simple, a tram corridor spine with short four storey, pedestrian orientated streets lying at right angles to it. The buildings are festooned with balconies and climbing plants, the roofs covered with photovoltaic panels and the landscaping dense and natural, with an ethos of guided nature rather than manicured control. The spaces between the buildings are casual and less defined in terms of public/ private domains than we create, kids abound and play areas are well integrated.

Cars are present (regulations in Freiburg are one car per household) and while casual use of the street space is allowed, they are generally accommodated in a large multi-storey car park, with legal agreements in place where residents buy a space if they have a car. Refuse vehicles are catered for in the conventional way and there is no sign of the underground car parking and sophisticated underground refuse recycling systems that you find in areas such as Hammarby in Stockholm.

People live in apartments with a balcony and good outdoor space, space heating is kept to a minimum and is provided by a district heating system and power from photovoltaic panels. The whole environment is well cared for – apart from the obligatory graffiti, a tolerance of which seems incongruous with the Germanic way (it must be regarded as a desirable art form). It all adds up as a good place to live.

So what can we learn?

From the visits we have made to exemplar regeneration projects, we have developed a view of where we are in relation to the northern European neighbours against which our government likes to benchmark us. The depressing truth is that we are well behind the best in Sweden, Holland, Norway and Germany. The Scottish Government recognise this, but catching up is a long and difficult process and acceleration is required.

A huge amount has been written on strategy and place-making. We all know the targets but we seriously need to deliver this process. This involves government at all levels.

An integration of agendas on this level requires the city as the driving force. Land must be acquired and infrastructure only works on a large scale, so issues like transport, schools, sewage and power need to be planned a generation in advance. In theory, this is what our Urban Regeneration Companies were formed to do, but they need strong political support and steady finance over a long time frame to achieve success.

We need faith in planning. The vital act of actually planning our cities has been devalued in favour of planning as a type of pragmatic development control. Planners also need the skills to do this effectively, which now very often exist within the private sector. Perhaps we need to look back to the process that created the new towns and try to do something similar around today’s agendas, with an integration of public and private sectors.

We need to follow the German principle of extending existing settlements rather than leapfrogging into new settlements as seems to have become the UK aspiration.

The private sector have a big role to play, but the role of the developer needs to be clarified and focussed more on the delivery of the product (and yes, making a profit from it) rather than the land speculation and master planning aspects of the current process.

There is a very high level of long term “stewardship” embedded in the whole European process and the continuing aftercare of a neighbourhood seems to be founded on local political and community power. There is a growing role here for our experienced group of Housing Associations.

In the UK, environmental issues are often seen as a threat, or something to be imposed, rather than regarding “greenness” as an opportunity to form a focus to promote community integration.

What could we teach them?

Impressive as Vauban is, we didn’t leave feeling that our approach in Scotland had nothing to contribute. While I admire intellectual rigour and a well-integrated process, I also look for a sense of enclosure of space which Vauban (and much contemporary German housing) seems to ignore at the basic layout level.

We build “closed” corners and we differentiate more between public and private domains. Much of this is perhaps rooted in climate and driven by a perceived requirement for social separation, but it does create very distinctive spaces. This is both costly and difficult to do, but provides a basic structure which is usually more attractive that the “open ended block” structure found in much contemporary northern European housing.

If we could take the political and community will of a city like Freiburg and marry it to the place making skills of some of the best Scottish designers, then we could seriously put our country on the regeneration map and perhaps one of the Scottish cities might be the next home of European sustainable urbanism.

|

|

Read next: Procurement

Read previous: Minecraft

Back to July 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.