South America

13 Jan 2012

After a recent tour of South America and the opportunity to visit one of Brazil's notorious favelas Eugene Mullan, of Smith Scott Mullan, gives his take on a very unique type of urbanism.

We stop at a road block, there’s a sense of uneasiness in the mini bus, “the drug lords have closed the street, we need to wait” says our guide. I get a sense of deja vu from my upbringing in Belfast, being in a situation which is out of my control. This place is obviously different, the normal rules don’t apply, we have just arrived in Rocinha the largest favela in Rio de Janiero.Fa ve’ la – an urban slum or ghetto, illegal squatter settlement.

The safest way to visit Rocinha is to join the Favela Tour Company which has been given the blessing of the local people. Our tour guide, Jan, issues clear instructions, “only take photographs when I say so, don’t photograph the drug dealers – they’re the ones on the mopeds with no number plates”. There is obviously no shortage of them!

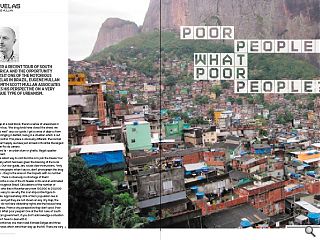

Rocinha is one of the 20 favelas in Rio and an estimated 600 throughout Brazil. Calculations of the number of people who live in Rocinha vary from 100,000 to 250,000 and it’s easy to see why this is an impossible figure to calculate. Approximately 20% of Rio’s population live in favelas and yet they are not shown on any city map, the people do not have citizenship rights and the houses have no address. From a city perspective they don’t exist. Poor people! What poor people? One of the first rules of South American government, if you don’t acknowledge a situation you don’t have to deal with it.

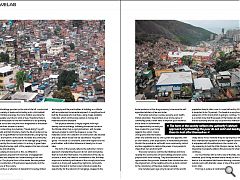

Rocinha has one main road, Estrada Dalgea and three minor roads which wind their way up the hill. There are very few cars but lots of mopeds. There are no parks or open spaces, there are no proper streets, just alleyways (becos) weaving between the rocky outcrops and the makeshift buildings. It can take up to an hour and a half to walk though the becos to get to one of the minor roads. There are no planning laws, no master plans, no building control, no state provision of social housing, no public transport; this is “every man for himself”. Accommodation is built in a highly haphazard manner, three, four, five stories built on top of each other, by different people with materials they managed to beg, borrow and steal. In the poorest areas, Macega and Roupa Suja, these are merely shacks constructed from corrugated iron sheets with no running water or electricity. In the more established areas there is painted blockwork and sometimes even ceramic tiles.

For many people living at ground level this is an existence with no natural light, very poor ventilation and very close proximity to street life. Ironically, for those living at the upper levels they have one of the most desirable locations in Rio with views of the stunning landscape and the dramatic coastal edge setting. In some ways, a social layering not dissimilar to the closes of 17th Century Edinburgh Old Town.

There is an uneasy dynamic between the official city policy of pretending these places don’t exist and the visual reality. Not least the sheer physical presence of these areas stretching up the dramatic hills, like a carpet of twinkling lights at night, forming a back drop to the better known natural Rio icons of Copacabana and Ipanema Beach.

It is over a hundred years since the early settlers arrived from the countryside, attracted by the opportunities that work in the city offered. They built their houses on unused or undesirable land, often on the side of the hills. There were regular attempts to remove the areas with the authorities finally accepting them in the 1970s and starting to grant land title. The practicalities of a neighbourhood such as this means water supply, drainage and utility services have developed slowly, with the authorities refusing to provide basic services. Provision of electricity is easy to see, with cables suspended from poles and buildings, weaving their way across the area. The system of rubbish collection is haphazard and ineffective with people carrying their rubbish to the streets for erratic collection by the authorities, forming a significant health hazard.

With the passage of time some areas of the neighbourhood have become more sophisticated. There is a market for buying and selling properties with a flat at the top of the hill (furthest from the city centre) valued at approximately 30,000 to 35,000 Brazilian Reals (equivalent to £10,000) and those at the bottom of the hill twice that value. The average salary of the people of the favela is between 600 to 900 Reals (£200 to £300) per month. In Brazil there is no requirement to pay tax unless you earn more than 1,200 Reals per month.

So what is life in a favela like? Noisy, smelly, intense, with the drug lords in charge. Their life expectancy is approximately 25 years, it must be a good life while it lasts! As is often the case with this type of area, only a small percentage of people are actually involved in the drug world, others choose to follow the “lei do silencio” (the silence law) and stay out of trouble. The people are here because they have no choice; if they want to access the work opportunities of the international city the favelas provide the only realistic living option. People work together to look after each other, they develop a strong sense of community and there is clear evidence that people like this aspect of the neighbourhood and choose to stay, improving their property.

The Favela Tour Company provide funds for the local Para Ti education project and our tour included a visit to the school buildings perched on the side of the hill, constructed over a variety of levels and including a 4m x 8m football pitch. Families are large, the more children you have the more people you have to work or beg. Therefore there is limited enthusiasm for this mini workforce to be spending time at school and only the most enlightened or the better-off allow their children to attend.

An interesting documentary “Favela Rising” by Jeff Zimbalist and Matt Mochary charts the life of Anderson Sa, a former drug trafficker turned revolutionary using hip hop music and rhythms of the street. He rallies the community against the violent oppression of the teenage drug armies, sustained by the corrupt police. It is a story of great hope reflecting the human spirit of the people in the face of social injustice and adversity.

Studying an area such as this, so different in development, physical form and rules of engagement broadens and deepens our understanding of our own system. This physical form of the favela, like everywhere else, is a reflection of the physical requirements and the structure of the society.

Rocinha is a reflection of demand for housing, limited land supply and the practicalities of building on a hillside with an unplanned incremental approach. A neighbourhood built by the people who live there, using cheap, available materials, which continuously evolves as money and materials become available.

The physical aesthetic is highly organic with high density low rise buildings, following the natural curves of the hillside rather than a rigid grid pattern, with facades variously angled to catch the breeze or a view. The materials consist of a collection of construction site discards and scraps which would now be classified as “recycled” goods. The result is a consistent, distinctive response to the practicalities, with limited influence of beauty for its own sake.

The form of the society reflects the authority’s historic approach of pretending the poor do not exist and leaving them to look after themselves. The attraction of the city as a source of work, the need for somewhere to live, the deep suspicion of authority and hatred of the corrupt police force results in a strong self-supporting, tight knit, community. However the lack of normal social controls provides the opportunity for the network of rival gangs, steeped in the brutal existence of the drug economy, to become the self-appointed arbiters of law and order.

The human outcome is serious poverty, poor health, limited education. The positives are a strong sense of community pride, a work ethic to improve your existence and a sense of achievement and responsibility for what you have created for your family (against the odds!). I had a strong sense that the favelas offers one extreme and our own system the opposite, with an over reliance, even expectation, of institutional provision. Would it be possible for self build, more community control and less regulation to capture the power of our people to shape their own environment?

There are numerous community initiatives and more recently the construction of new buildings and even some purpose built social housing. They are welcome for the opportunities they provide, however their introduction into the physical form of the neighbourhood is a stark contrast to the consistency of the place made by people.

One hundred years ago only 10 percent of the world’s population lived in cities; now it is over half and by 2050 it is projected to be 75 percent. The favela is a one physical expression of this trend which is going to continue. There is a certain irony that the people of the favelas are vital to the Rio economy and the city could not exist without this cheap labour force. However they are synonymous with Rio’s international reputation and this negative connotation is unpopular with the authorities in the context of a city preparing to host the 2016 Olympic Games. So the imperative to properly address this pressure for urban living continues.

Our tour finishes with a visit to one of the flats, raw materials, poor fitting windows and a variety of door types lead us to a substantial tiled terrace forming a stunning outside room with dramatic views of one of the world’s iconic cities.

This truly is a place of contradictions.

|

|

Read next: Govan Renewal

Read previous: Keeping the Faith

Back to January 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.