Foster and Partners £70 million Sage centre at Gateshead represents a major investment, but the brief appears to have been driven more by a commitment to accessibility than a love of good music.

11 Feb 2005

by Penny Lewis

The Sage Gateshead, the North East’s new £70million performing arts centre, opened just before Christmas. SAGE is the final piece in a triptych of iconic public projects clustered around the edge of the Tyne, which includes the Baltic and the Blinking Bridge by Wilkinson Eyre.

Foster and Partner’s building consists of a large steel shell-like structure that over-arches three performance spaces. The volumes between the shell and the halls are devoted to circulation and other public uses.

The slug-shaped arts centre will be a great asset for music lovers in Gateshead, Newcastle and the North East. In political terms it underlines the commitment of the city to continue to develop the facilities as part of its strategy to become known as a cultural centre, but what about the design?

There has been a lot of discussion about whether the building is out of scale. Although it is in Gateshead, within a wasteland, the centre’s greatest asset is the view that it provides towards Newcastle city centre. The old industrial site sits at the haunches of the Tyne Bridge, so it’s hard to say what an appropriate scale might be – this building is anything but contextual. The building is not attempting to form a piece of urban fabric; its charm is that its form is entirely alien, even if the arches of the slug’s back mirror the curves of the Tyne bridge.

The building is disappointing in two respects, first in the relationship to the surrounding urban landscape and secondly in the organisation of the public areas.

When SAGE opened in December queues of people huddled around pools of muddy water, waiting for an opportunity to get onto the stairs that would take them from the riverside walk to the new cultural attraction.

The relationship between SAGE and the other Tyneside attractions is the project’s most striking failure. Terraced parking occupies most of the steep slope between SAGE and the river, and a miserable flight of steps, in concrete and galvanised steel, winds its way from the open space in front of the main entrance across the car parks to the waterfront. It is hard to imagine how, in a climate where planners spend so much time talking about the public realm, that this particular landscape could have been so neglected.

The second failing relates to the brief. SAGE tries, like many of its type, to fulfil a certain set of demands that contradict the aspiration to create a meaningful place. According to Foster’s office the key drivers for the design were accessibility, the creation of a new internal public space, or urban room, and an informal ambience that allowed performers and public to mix. The brief sounds very public spirited, but you can’t prioritise these issues without it having implications on the way the rest of design develops.

Walking into SAGE is like arriving at a drawing of a performance venue in which you can see the bare bones of the proposals but the detail and elaboration has yet to be drawn in. There is no evidence from the shell of the building of an engagement with a considered client. SAGE seems like a competent design solution, in the same way that an ASDA supermarket feels like a good machine for selling food, but feels soulless. The clinical quality of the building is not a product of a strong rational approach to the organisation of space, but rather an indulgent approach to the idea of creating an ‘urban room’. This is not a building dedicated to the celebration of great music, but more a generic container of human activity.

The problem with creating a big ‘urban room’ is that the entire space becomes dedicated to general milling around, and the sense of arrival at the important spaces, the process of developing expectations unravelling until the visitor arrives at the most significant space, the concert hall, is destroyed.

The street-like public space feels just like a street. It may have been the architect’s intention, but is this appropriate as the first experience of a music hall? You can’t imagine the classic moment in The Godfather III where Don Coreleone’s daughter is shot on the golden steps of a Sicilian opera house being played out at the gaping entrance, or even on the grand stairs of SAGE. The building lacks the passion and drama associated with the best of its building type. Walking into SAGE is like entering Eldon Square, Newcastle’s shopping centre. There is no sense of arrival; no real entrance point. The distribution of little retail islands scattered along the route adds to the sense of consumer drift.

There are several grand staircases in the building – they are big, but they are not grand. They are tucked away, and they rise towards the back dark side of the building, turning their backs on the views of the Tyne. There is no sense of the stairs rising through space.

This idea that public buildings are special places that people like to hang out in is over rated. The truth is that you wouldn’t go to the caf... at SAGE to hang out. It is located underneath the stair without the benefits of views out.

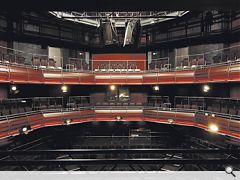

That said, the acoustic performance is good and the second space dedicated to folk music, Hall 2, is a fantastic bit of escapism. Once inside this round theatre, you finally feel that you may have come to a place, with its rich colour and warm materials, which was designed as a space dedicated to music.

Photography by Nigel Young

courtesy of Foster and Partners.

Back to February 2005

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.