Scottish Slate: Island Rebirth

23 Jan 2024

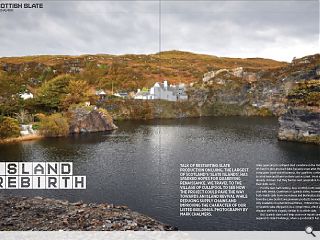

Talk of restarting slate production on Luing, the largest of Scotland’s ‘slate islands’, has sparked hopes for a quarrying renaissance. We travel to the village of Cullipool to see how the project could pave the way towards an island revival while reducing supply chains and improving the character of our listed buildings. Photography by Mark Chalmers.

Slate quarrying in Scotland died sometime in the 1960’s. It’s hard to give an exact date, because even after the slate companies went out of business, the quarriers continued to work here and there on their own account. Most were already old men, but they had no next generation to pass their skills on to.

For the next half century, new Scottish roofs were clad with Welsh, Cumbrian or Spanish slates; however, both Welsh slate from Snowdonia and Burlington slate from the Lake District are premium products nowadays, only available on extended lead times. Witness the crates of Spanish slate shipped in as a compromise, which are cheaper and look vaguely similar to Scottish slate. But Spanish slate can’t help once roof repairs are required to listed buildings, when a good match has to be robbed from another structure. This has led in ever-decreasing circles, since fewer historic buildings are demolished these days, yet more and more require re-slating. We could have predicted this, and perhaps even done something about it before it was too late. Scotland’s stone and slate quarrying industries went into decline during the first half of the 20th century, fell silent during the War, and were in danger of extinction by the 1950’s.

In 1959, James Shearer wrote in the RIAS Quarterly, “It is widely believed that in Scotland we cannot afford to use stone. Stone is not used because it is too dear, and it is too dear because it is not used.” Scottish stone and slate were caught in a Catch-22 situation. Our native slate industry worked several different locations: on the slate islands of Easdale, Seil, Luing and Belnahua off the coast near Oban; at Ballachulish to the west of Glencoe; West Highland slate found in a belt which stretches diagonally along the Highland Line from Luss and Aberfoyle to Birnam and Craiglea; also in the slate hills above the Glens of Foudland in Aberdeenshire. Ballachulish was the largest enterprise, and quarrying was run along the same lines as the great quarries at Dinorwic and Penrhyn in Wales, with several levels or benches linked by inclines. The Laroch quarries at Ballachulish produced 25 million roofing slates a year and had their own railway branch, which Dr Beeching ripped up in 1966, around the same time the quarries shut. The imposing span of Connel Bridge is one of its last remnants. Immediately after Ballachulish closed, there was still Scottish slate to be had, either by salvaging demolition sites for slate which could be dressed and re-holed, or by robbing waste tips at the old quarries.

Demand was relatively low, because interlocking concrete tiles were in fashion and most Modernist buildings had flat roofs. By the 1990’s, reclaimed Scottish slate had become expensive due to its scarcity, and James Shearer’s sad prophecy had come true. The rebirth of Scottish slate has been mooted for quarter of a century. In the early 2000’s, the Scottish Stone Liaison Group, British Geological Survey and Historic Scotland investigated Khartoum quarry at Ballachulish and the quarries high above the Glens of Foudland between Inverurie and Huntly. Old workings were surveyed and blocks of slate removed for analysis at the University of Paisley: that demonstrated the slate was perfectly suitable, but it wasn’t so easy to deal with the commercial and Planning issues involved in re-opening a slate quarry. Proposals for Foudland never proceeded beyond an initial burst of enthusiasm, but in 2005 it became the first topic I wrote about for publication in a magazine. Even though they’d been abandoned since the Great War, a surprising amount still lay around the quarries on the Hill of Foudland, including the remains of scathies which the slate splitters sheltered in. The quarries are exposed and bleak – but the reward for persisting in that tough environment was a beautiful midnight blue slate which sparkles with crystals of Fool’s Gold.

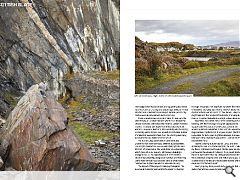

Two decades after the exploratory work at Ballachulish and Foudland came to nothing, a new proposal emerged to restart production on the Slate Island of Luing, a few miles from Oban. Like Ballachulish, quarrying on Luing ended in the 1960’s. The last Cullipool quarryman, Hugh, is now in his 80’s – but the quarries are far from exhausted. The British Geological Survey estimates that the slate runs through Luing in a 20 metre deep seam. The Slate Islands are well-named, and the Luing islanders were monomaniacs. Their cottages had slate roofs, slate walls and slate flagged floors: they dug through the thin soil and built directly off bedrock – which is also slate. The garden walls were built from slate, too, and you can guess what the footpaths are paved with. You may think you know “slate”, but slate from Luing and Easdale has a unique characteristic: it’s gunmetal grey and the surface is subtly rippled with crenulations. That texture is distinctive, since almost every other slate is smooth. Luing relied on coastal puffers to transport its slate to towns and cities on the western seaboard which formed its market: Iona Abbey and Glasgow University are both roofed in Luing slate. At its peak, production across the various Slate Islands reached eight or nine million slates each year, and the quarries on Luing were mechanised with narrow gauge railways and steam-powered cranes. The new initiative on Luing stands a better chance of success than previous efforts for several reasons.

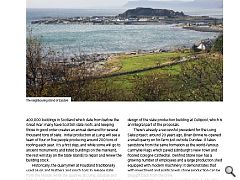

The mineral rights to the quarries are owned by the Isle of Luing Community Trust which is keen to re-open one of the quarries, and Historic Environment Scotland (HES) will support the project, since supplies of Scottish slate for repair projects are now virtually non-existent. Supply and demand have begun to align in a way they haven’t done before. As Graham Briggs of HES explained, there are around 400,000 buildings in Scotland which date from before the Great War: many have Scottish slate roofs, and keeping those in good order creates an annual demand for several thousand tons of slate. Initial production at Luing will see a team of four or five people producing around 200 tons of roofing each year. It’s a first step, and while some will go to ancient monuments and listed buildings on the mainland, the rest will stay on the Slate Islands to repair and renew the building stock. Historically, the quarrymen at Foudland traditionally used plugs and feathers and pinch bars to release slate from the hillside, while the quarries at Luing, Easdale and Ballachulish used black powder to blast blocks of slate from the rockface. Modern quarries in Spain use wiresaws to slice slate from the working face, but the new workings at Luing will use an excavator with a hydraulic picker to free a few tons (around two weeks’ of production) at a time.

Once a block is released, it will be loaded onto a dumptruck and taken into a new workshop where diamond saws and CNC machines can process it. Machines will split each block into roofing slates, and potentially also slab which can be used for worktops, hearths and wall cladding. Will Tunnell of WT Architecture is currently working on the design of the slate production building at Cullipool, which is an integral part of the proposals. There’s already a successful precedent for the Luing Slate project: around 20 years ago, Brian Binnie re-opened a small quarry on his farm just outside Dundee. It takes sandstone from the same formation as the world-famous Carmyllie Flags which paved Edinburgh’s New Town and floored Cologne Cathedral. Denfind Stone now has a growing number of employees and a large production shed equipped with modern machinery: it demonstrates that with investment and political will, stone production can be brought back from the brink. As architects our focus is on roofing slate, but for the Isle of Luing Community Trust, quarrying is an integral cog within a bigger machine. The workshops will offer apprenticeships, leading on to high value jobs which in turn recycle money into the island’s economy, retaining people and skills on Luing, and ultimately enabling new houses to be built at Cullipool. Slate quarrying could help to keep island communities alive. On a macro scale, the objectives of the Luing Slate project include encouraging the use of appropriate materials for our native architecture, re-discovering knowledge which has been lost, and supporting Scotland’s rural economy by creating and sustaining a skillbase. It may also become a demonstration project for how community land ownership can promote local enterprise.

From an environmental point of view, it’s precisely the kind of Made-in-Scotland project which could bolster the circular economy and reduce the need for carbon-intensive imports. Crucially, any waste from the project won’t be wasted. Cullipool is built on a slate waste tip which is being eroded by winter storms, and around 30,000 cubic metres of material is needed to shore it up. Re-starting quarrying will enable the sea defences to be rebuilt. The Isle of Luing Community Trust’s work also underlines that there are many different sustainabilities. The airtight membranes, MVHR ventilation systems and 300mm-of-Warmcell-in-the-walls strain of sustainability which many of us pursue only addresses a building’s energy in use. At the opposite pole is John Ruskin’s vision of sustainability, using local materials and fostering crafts skills: it’s that much broader view of what makes communities sustainable which is relevant on Luing. The impact of the project is also psychological.

The quarries at Cullipool hark back to the island’s industrial heritage: the project will hopefully transform the mindset of islanders, changing slate from a piece of history into a modern industry which is part of their future. The project might also alter the mindset of architects, changing slate from an imported lookalike into a high-value native material. Meantime, the Community Trust is currently pursuing funding, with the first stage of a grant application to support slate extraction and the construction of the workshop already submitted to the Scottish Government’s Regeneration Capital Fund.

If all goes to plan, the first Luing slate for sixty years might be delivered in around two years’ time, making its way across Cuan Sound on the island’s little ferry. I spent a stormy autumn day on Luing, and after speaking to Colin, Rob and Hazel from the Trust, I pulled on my fleece and boots and headed into the quarries which lie just beyond the village of Cullipool. It’s a violent landscape: the rock was transformed by unimaginable forces during the Caledonian Orogeny, over 470 million years ago, leaving a great mass of twisted and folded slate stained with iron oxide and striated with quartz. Quarrying may have paused sixty years ago, but Luing’s slate is half a billion years old and indestructible.

|

|