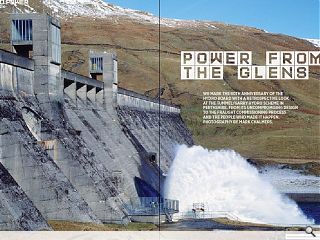

Hydro: Power from the Glens

13 Jul 2023

We mark the 80th anniversary of the Hydro Board with a retrospective look at the Tummel/Garry hydro scheme in Perthshire. From its uncompromising design to the fraught commissioning process and the people who made it happen. Photography by Mark Chalmers.

This autumn marks the eightieth anniversary of the creation of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electricity Board. Its objective was to develop a series of hydro-power schemes to capture the wasted potential of lochs and rivers, which would bring electricity to rural areas, helping in turn to develop industry and ultimately delivering a better quality of life. In order to succeed, the Hydro Board had to make connections, and its first was the appointment of a visionary politician called Tom Johnston. Johnston was a Scots patriot and staunch socialist; his book, Our Scots Noble Families, was a scathing critique of the country’s lairds.

In 1941, he became Secretary of State for Scotland and his vision, as he put it, was to create “large-scale reforms that might mean Scotia Resurgent”. Two years later in 1943, when Johnston became chairman of the newly-created Hydro Board, it became clear that his ambition for Scotland was comparable to Roosevelt’s New Deal for Depression-era America. The New Deal acted as catalyst for the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) hydro-power projects built in the American South during the 1930’s and 40’s. The Hydro Board began work immediately, taking over the assets of the Grampian Electricity Company in Perthshire. The Grampian Company, as well as British Aluminium and the British Oxygen Company (BOC), developed some large-scale hydro-power before 1943, but they were blocked repeatedly by a right-wing lobby representing coal barons and sporting estates. BOC eventually had to abandon its plans for a hydro scheme at Corpach, and eventually built their carbide smelter on Oddafjord in Norway instead. Johnston was determined that, in future, industry would be attracted to Scotland rather than being chased away.

In order to support that aim, he insisted that local companies become involved. Harland of Alloa built turbines, Weirs of Cathcart provided valves, J.M. Henderson & Co. of Aberdeen supplied cable cranes, Bruce Peebles of Edinburgh and Bonar-Long of Dundee made power transformers. Nowadays, that would be called a Green Industrial Policy… Similarly, the schemes’ architecture had to be inherently Scottish, too. In 1941, Johnston contributed a foreword to a little book called Building Scotland: Past and Future, which was written by Alan Reiach and Robert Hurd, who went on to found Reiach & Hall and Hurd Rolland. Building Scotland was a rallying cry for the creation of a modern Scottish architecture: presciently, it features the hydro schemes at Hammarforsen in Sweden, Brislach in Switzerland, and the Norris Dam in Tennessee, which was the lodestar project of the TVA.

Nor were Hurd and Reiach alone in envisaging that International Modernism could hybridise with a national vernacular. In 1957, Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhardt published Architecture of Bosnia and the Way towards Modernity, which argues that the architecture of a modern nation should be built on vernacular foundations. The result was a precursor to the Critical Regionalism which emerged in the 1980’s. The North of Scotland Hydro Electric Board’s dams and power stations are among the greatest achievements of post-war Europe, and understandably we often concentrate on the engineering superlatives. The tunnels driven for the Tummel-Garry scheme alone stretch for 100km, including a 7.5km pressure tunnel over four metres in diameter which links Stronuich in Glen Lyon to Lochay Power Station. Several world records were broken during tunnel-driving in Breadalbane. But the Hydro was also an enlightened patron to Scottish architects.

When Robert Matthew returned to Scotland from London in the 1950’s, he set out to create a Modern Scottish architecture: in the Breadalbane scheme, you can grasp a sense of its possibilities. 2023 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the commissioning of the scheme, where high level reservoirs feed a series of powerhouses including Cashlie, Dalchonzie and Lubreoch, with its control centre and largest power station at Lochay. Matthew’s work achieves a hybrid of modern and traditional which goes beyond the stripped-back Classical turbine halls at Clunie and Faskally designed by Tarbolton & Ochterlony, or further north, the neo-Baronial powerhouses of Shearer & Annand at Affric and Conon.

Yet these power plants are little known compared to his senate towers at Dundee and Edinburgh Universities or the original passenger terminal at Turnhouse aerodrome. Matthew used masonry in a less rhetorical, more asymmetrical way than his peers such as James Shearer, Robert Hurd and Ian Lindsay, about whom Mansfield Forbes wrote, “His interest in the Scots baronial style was by no means antiquarian, and in the fluid use of small rubble and harling he saw a good foundation for a more plastic, modern Scots architecture carried out in concrete.”

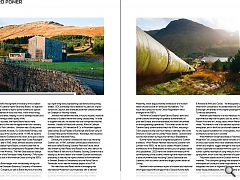

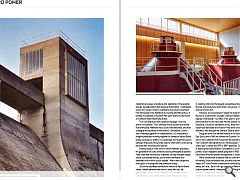

What Matthew himself described as “load-bearing Modernism” at Lochay power station consists of curving planes of uncoursed rubble which have weathered the harsh glen winters and impart a rugged strength to the buildings. The rubble is quartzite rock blasted from the Lyon-Lochay pressure tunnel: a perfect example of using what you find in the place it sprang from, which is the very definition of sustainability. The power stations took on Scottish forms as well as materials. The courtyard typology was adopted for the switchyards at Lochay and other large stations, the valve towers integrated into dams in Highland Perthshire hint at their baronial tower house predecessors, and James Shearer even used a re-entrant plan for his power station at Loch Shin. Lochay is simultaneously Modernist and Scottish.

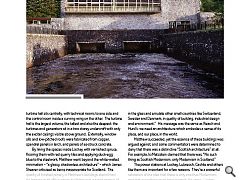

The turbine hall sits centrally, with technical rooms to one side and the control room inside a curving wing on the other. The turbine hall is the largest volume, the tallest and also the deepest: the turbines and generators sit in a two storey undercroft with only the exciter casings visible above ground. Externally, window sills and low-pitched roofs were fabricated from copper, spandrel panels in larch, and panels of as-struck concrete. By lining the spaces inside Lochay with varnished spruce, flooring them with red quarry tiles and applying duck-egg blue to the steelwork, Matthew went beyond the white-walled minimalism – “a glassy, shadowless architecture” – which James Shearer criticised as being inappropriate for Scotland.

The quality of finished joinery in Matthew’s buildings stems from his training in an office where his father was a junior partner of Robert Lorimer, who still adhered to the Arts & Crafts ethos. That allows us to place Robert Matthew within a continuum, which takes in James MacLaren, Mackintosh and Lorimer at the turn of the 20th century, each of whom was steeped in Scots tradition yet well aware of developments in contemporary architecture. They were followed a generation later by the revival of Scottish Nationalism in the 1930’s, which influenced Lindsay and Hurd, as well as Basil Spence and Matthew himself, each of whom contributed to Scottish Modernism after the War. At the same time as the Breadalbane scheme was on the drawing board, Matthew called for Scotland to, “Look at herself in the glass and emulate other small countries like Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark, in quality of building, industrial design and environment.” His message was the same as Reiach and Hurd’s: we need an architecture which embodies a sense of its place, and our place, in the world. Matthew succeeded, yet the essence of these buildings was argued against, and some commentators were determined to deny that there was a distinctive “Scottish architecture” at all. For example, Isi Metzstein claimed that there was, “No such thing as Scottish Modernism, only Modernism in Scotland.”

The power stations at Lochay, Lubreoch, Cashlie and others like them are important for a few reasons. They’re a powerful refutation of the idea that there is only one true Modernism, and that everything must tend towards the same. Lochay Power Station is, contrary to Metzstein, emphatically Scottish Modernism rather than merely “Modernism in Scotland”. The Breadalbane projects proved that power generation can be integrated into a wild landscape – and far from deterring tourists, visitors are actively drawn here to stand in awe. The reservoir at Errochty is impounded by a diamond-headed buttress dam: at sixteen storeys high and almost three-quarters of a kilometre long, it weighs half a million tons and is one of the largest in Europe.

At Lochay there is an integration of load-bearing masonry with a structural frame, the marriage of craft finishes with industrial processes, and above all a celebration of renewable energy, decades before that became fashionable. Sustainable power isn’t novel, it wasn’t invented by the Green movement: first harnessed in the Highlands during the late 19th century, it fulfilled its potential in the post-War years thanks to the North of Scotland Hydro-Electricity Board. This is architecture with a political message – but one which isn’t partisan. Tom Johnston was a socialist and Home Rule enthusiast, Matthew was a Scots internationalist, and their colleague the secretary to the Board’s Consultative Council was a lifelong supporter of independence. It’s impossible to imagine politicians working together to create the Hydro Board today, because our politics is so polarised, and a gulf has grown between the public and private sectors which didn’t exist during the post-War reconstruction period. Another aspect is the world in which Matthew practised. His generation of Scots architects took a philosophical position. They knew that architecture mattered, so they thought deeply about it, published articles, put forward manifestos and defended their work in public debate. With a few exceptions, that rigour is missing from the profession today.

Out of the countless connections which the Hydro Board made, I have a personal one which I carry with me. My grandfather’s cousin, Doug Neillands, was secretary to the Consultative Council of the Hydro Board. He played a role in creating what was the biggest renewables programme in Europe, but because he died while I was young, I didn’t get the chance to know him. However, during lockdown I began to research his life. Born the son of a blacksmith, Douglas Chalmers Neillands took a law degree in Edinburgh – but after a few years in practice, war broke out and he was recruited into the Special Operations Executive, Churchill’s clandestine army. After the War, he became an advocate and moved in the same circles as Ian Hamilton, who brought the Stone of Destiny back to Scotland. Doug set down our national history in his book, Scotland’s Epic Story, and in 1949 he drafted the Scottish Covenant, which was Scotland’s first movement for political devolution. The Covenant was signed by two million people – more than voted “yes”

in either the 1979 or 1997 referenda. Doug’s role in steering the Hydro Board’s Consultative Council was also pivotal, since it helped to defeat proposals in 1963 which would have killed off hydro-power development in Scotland. We’re conditioned to believe that our own families consist of ordinary, unaccomplished folk, and that only the talking heads on TV and Twitter contribute to human progress. That simply isn’t true. Each time I go climbing in Perthshire and pass a hydro-power station, I take pride in what Doug Neillands helped to create while working with Tom Johnston, Robert Matthew and thousands like them.

|

|