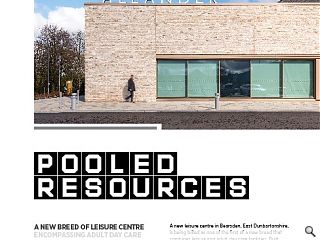

Allander Leisure Centre: Pooled Resources

13 Jul 2023

A new breed of leisure centre encompassing adult day care services promises to serve as a one-stop-shop for health and wellbeing. We tour Allander Leisure Centre to find out how new forms of inclusivity can unite communities post-covid. Photography by Chris Humphreys.

A new leisure centre in Bearsden, East Dunbartonshire, is being billed as one of the first of a new breed that combines leisure and adult day care facilities. Built around an evolving approach to the design of health and wellbeing amenities it emphasises value and care and brings leisure and adult day care facilities together under one roof, removing physical and mental barriers to participation.

Embodying inclusivity the centre exemplifies East Dunbartonshire Council’s vision for a combined facility that draws together the functional aspects of an adult day care facility and leisure centre, raising novel synergies in the process such as locating a hydro pool next to the swimming and learning pool.

A direct replacement for the original sports complex built in 1978 the £42.5m Allander Leisure Centre offers support services for adults with learning disabilities as well as a multitude of sports facilities including a swimming pool, games hall and squash courts. Its architects, Holmes Miller, tells Urban Realm they view it as a potential template for future civic projects.

Belying its 10,000sq/m size, upon approach, the building hides its mass behind a rational facade, as project architect Nada Shehab told Urban Realm during a spring visit shortly after it opened: “We tried to keep the massing as similar as possible while making it more modern. The concept was cascading forms, from the eight-court games hall which we pushed back into the site to make it less dominant, to the adult resource building that is on a more human scale and is surrounded by sensory gardens.”

Fortunately, the massing is about the only thing to carry forward from the blue sports shed of old, which is still standing as phase two works starting in earnest, for providing a startling before and after view. Encompassing a 12m ‘sports dome’, sheltering two football pitches and a tennis court, the later addition will employ a modern geometric shape to contrast with the brick building but for now it exists solely on the drawing board.

Hosting physiotherapy treatment, training kitchens, arts and crafts, dance and music rooms the multi-purpose venue risked becoming a confusing agglomeration of facilities and services but such fears are eased by the incorporation of two dedicated entrances, a primary public entrance and a side entrance to the adult day centre. The former opens onto a calming triple-height timber-clad atrium that doubles as an events space and cafe, framed by a cantilevered stair and prominent ‘A’ signage. Soaring upwards to a timber-lined roof the space doubles as a multifunctional hall with the necessary flexibility to meet changing levels of demand throughout the year.

“It’s good to have different types of users in the same building and not have the adult resource centre users isolated”, explains Shehab. “Kirkintilloch and Kelvinbank Resource Centre both needed new facilities. Why not do them together in a combined health and wellbeing centre? A sensitive boundary between the two was required but it is so much better. It’s all about sharing.”

Drawing different resources together demands a civic frontage, achieved via a galleria that will eventually become a street, bisecting phases one and two. Its position is far from arbitrary however as Shehab explains: “There were a lot of constraints to the site such as a big mains sewer and flats, the only place the building could go was here. It’s a bit more outward-looking, the way leisure centres were designed back in the day there weren’t any windows while we are all about natural light.”

In contrast, the daycare centre is more reserved, with neutral earthen tones and upgraded acoustics to dampen sound. Curved corridors and quiet spaces are floodlit by daylight from above adding to the feeling of serenity. A direct link is also provided to the pool hall, with quiet and discreet changing rooms on the daycare side, away from leisure users.

Holmes Miller associate Joanne Hemmings commented: “Although it is the same building, we wanted it to have a distinctive feel. It was important to have a relaxing and calming environment whereas the leisure centre is more active. We created that with softer pastel shades and graphics.”

Throughout this area, the views out to the enveloping sensory garden, developed with LDA, are prioritised to increase the sense of domesticity. with Attention to detail stretching stretches to cork walls to assist navigation for visually impaired users who wish to feel their way around the spaces and all rooms are set back from the main hall with niche spaces and custom signage. Every room has its own symbol, name and texture signifier with braille at the bottom.

This approach extends to a Snoezelen room, a multisensory environment employing water, light and sound to provide a soothing and stimulating environment for people with developmental disabilities. Shehab added: “Contrast is not always good for people who use this facility so floor coverings and wall finishes are as subtle as possible with no contrasting lines or patterns. We also identify rooms by colour. The building users have different sensory needs with different activities emphasising sounds, sights and tactility. Everything on this side of the building is softer, there are no harsh colours or lines. We kept everything as curvy as possible, even the signs are curved.”

The heart of the building is the central pool hall, spanning almost the full width of the building with interior glazing maximising the sense of openness, a far cry from the Allander of old. Including a spectator gallery above the competition standard pool, in addition to a training pool and hoist, complete with a movable floor operated by hydraulic rods, this was also the most technically challenging element of the build. Shehab said: “By having screens at the reception and a small band of north-facing windows we could make the space feel less enclosed. We tried to get light in where we can and bring in the natural environment while avoiding glare on the water.”

Concluding the visit project director Ian Cooney said: “The heart of Allander is inspiring and uplifting health and wellbeing architecture, driven by social values. The design represents a pioneering health+wellbeing project on the back of our recent Meadowbank and Trinity/Bangholm projects – with Blairgowrie Recreation centre to come in the form of Scotland’s first Passivhaus Sports Hub. The overall result is a warm, welcoming building that breaks down barriers, improves lives and creates synergies between sport, culture and mental health.”

Drawing together buildings and services is the quickest route to bringing people together, an approach that has been well documented by joint campuses across the school’s estate. It is a philosophy gaining ground in healthcare and now the leisure sector too. Particularly as avoiding unnecessary duplication permits cuts to costs without impacting quality. It is an approach likely to gain momentum after testing the waters at Allander.

|

|