Graving Docks: Shipshape

23 Jan 2023

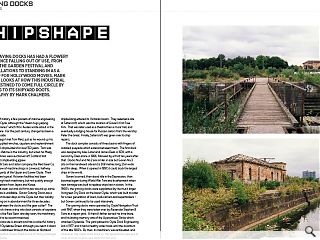

Govan Graving Docks has had a flowery history since falling out of use, from a seat of the garden festival and art installations to standing in as a backdrop for Hollywood movies. Mark Chalmers looks at how this industrial relic is destined to come full circle by returning to its shipyard roots.

Against the tide of history, a few pockets of marine engineering survive along the Clyde, although the “steam tugs yelping down a glade of cranes” which W.H. Auden wrote about in the 1930’s are long gone. For the past century, change has been a constant on Clydeside. Fifteen years ago I met Tom Reid, just as he wound up his firm which had supplied winches, capstans and replenishment gear to Clydeside’s shipbuilders for over 150 years. Tom was a spry gent with a lifetime in the industry, but when his Maag gear-cutting machines were auctioned off, Scotland lost another piece of its shipbuilding jigsaw.

Thomas Reid & Sons and sister company the Reid Gear Co. operated from a row of machine shops in Linwood, halfway between the shipyards of the Upper and Lower Clyde. Their circumstances were typical: Victorian facilities had been augmented with high tech machinery, but not quickly enough to stave off competition from Japan and Korea. While old tools wear out and old firms are wound up, some of the infrastructure is unkillable. Govan Graving Docks are a ghost left over from busier days on the Clyde, but their solidity means they’ve hung on in abandonment for three decades.

The connection between the docks and the gear cutter? The winching gear which draws a ship into dock consists of capstans built by companies like Reid Gear; one day soon, the machinery at Govan will need to be recommissioned. The graving docks site is ancient and has a colourful history. It lies at the end of Clydebrae Street, although you reach it down Stag Street, which continues through the docks as Highland Loan. It once connected Govan Road to one of many passenger ferries across the Clyde. The Clyde Navigation Trust developed the docks just as shipbuilding entered its Victorian boom. They selected a site at Saltercroft, which was the location of Govan’s first Free Kirk. That was later used as a theatre then a music hall, and eventually a lodging house for Russian sailors from the warship Peter the Great. Finally, Saltercroft was given over to ship repairs.

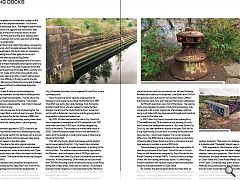

The dock complex consists of three basins with fingers of cobbled quayside which extend between them. The first dock was designed by Alex Lister and James Deas in 1874, with a second by Deas alone in 1886, followed by a third ten years after that. Docks No.1 and No.2 are similar in size but Govan No.3 sits on their landward side and is 268 metres long, 25m wide and 8m deep. When it opened in 1897, it could dock the largest ships in the world. Govan boomed, then stood idle in the Depression, then boomed again during World War Two and its aftermath when new tonnage was built to replace ships lost in action. In the 1960’s, the graving docks were supplanted by the much larger Inchgreen Dry Dock on the lower Clyde, which was built to cater for a new generation of liners, bulk carriers and supertankers – but Govan continued to be used intensively. The graving docks were operated by Clyde Navigation Trust until 1967, when they were taken over by Alexander Stephen & Sons as a repair yard. A friend’s father served his time there, and his lasting memory was of the Apprentices’ Strike which wracked Clydeside.

The yard passed to Clyde Dock Engineering Ltd in 1977, and it had a healthy order book until the downturn of the late 1980’s. By then, its machinery was antiquated, and whenever ship repair work dried up, the apprentices were put to work stripping pumps and replacing bearings. The docks have lain abandoned since they finally closed in 1988, although the gates are unlocked and lie open so the curious can wander in and explore the terrain. You’ll never experience another landscape like it. The negative space inside each dock is the inverse of a ziggurat: the docks have “altar steps” on either side, formed from massive blocks of silver granite. The steps form the barrel of the dock, leading down from the coping to subways and sumps, keel blocks and bilge blocks which now lie underwater. The half-flooded basins are melancholy places, occupied by a handful of sad ducks which navigate between the oil cans and floating debris. Nevertheless, the docks retain an impressive scale, from the meeting face of their gates to the curved dockheads under the retaining wall at Stag Street. Thirty-five years after closure, redevelopment of the docks has become a saga of failed masterplans and rejected planning applications. It’s another act in the great Clydeside drama that includes the Fairfield Experiment of the late 1960’s, and the UCS Work-In of 1971 which made Jimmy Reid a household name. The graving docks’ planning history is worth setting down as it demonstrates the difficulty in finding a use for the site which satisfies the Planners and Historic Environment Scotland.

So, why has it proven so difficult to utilise these three ship-shaped holes at Govan? The docks are Grade A-listed and acknowledged as being internationally important, so they need a developer and architects with rare insight and sympathy. The site sits on the Clyde, so SEPA are concerned about flooding. That means large parts of the site are undevelopable – but it hasn’t stopped the site’s promoters from trying. If Govan was more prosperous, its land values higher, the docks would have been filled in and built over long ago. Princes Dock to the east was lost to the Garden Festival in 1988, then Glasgow Science Centre with its perennially wonky tower which sits on the other side of the canting basin – yet the graving docks escaped. Finally, any investment appraisal in 2022 is bound to be sensitive to hardening interest rates and a weakening housing market. That doesn’t bode well for this site faced with a long list of exceptionals, including flood control measures, deep piling for the buildings and repairs to the dock gates.

The first roll of the dice by the site’s original promoter, Windex Ltd., was an outline application for a mixed residential and commercial development, made in partnership with Clyde Dock. One of the docks would be infilled, the other two flooded and their gates removed. That scheme was refused by Glasgow District Council in 1990. The Windex proposals were considered alongside a bid for compulsory purchase by the Clyde Ship Trust: a hint of the friction between heritage and commercial development. In 1993, approvals were granted to the Clyde Ship Trust for a maritime heritage centre, which included plans to restore the dry docks in order to display the historic ships City of Adelaide and County of Peebles. But that project died – although the City of Adelaide did make it to the adjacent Princes Dock, where it promptly sank. Next, the graving docks were the proposed site for Glasgow’s bid to preserve the Royal Yacht Britannia in 1997. That effort was led by the Clyde Heritage Trust, formed by architect Geoff Jarvis who also helped to create the New Glasgow Society and the Clyde Maritime Trust. Govan lost out to Leith as Britannia’s new home, and the graving docks regeneration scheme also keeled over. By 2002, Windex had passed the site to City Canal Ltd, which proposed a development of 500 residential units, 300 hotel rooms and over 11,000 sq.m. of offices designed by McGurn Architects.

The architectural moves were brutal: in 2003, Scottish Enterprise helped to fund the demolition of nearly all of the buildings, including the Grade A-listed pump house for Dock No.3. That left only the dry docks themselves and the derelict pump house beside Dock No.1. City Canal’s plans included infilling Docks No.1 and 3 to create basement car parking for the blocks of flats. This outline scheme was actually approved by the Planners – but the financial crash of 2008 put paid to it. A few years later, New City Vision Ltd became sole owners of the site. A new scheme by ZM Architecture included more than 700 flats including a series of tall blocks along Govan Road, along with a hotel, shops, restaurant and offices. According to Business Insider magazine, it was torpedoed by the Planners in August 2018 who described it as being “surprisingly poor”.

The application was refused. Once again, an alternative proposal emerged in parallel, when venture capitalist Jim McColl suggested bringing at least one of the docks back into commercial use. He used Inkdesign Architecture to draw up his proposals. Like Geoff Jarvis, McColl had genuine vision, but his plan was scuttled when CalMac’s hybrid ferries went awry and Ferguson Marine was nationalised. Yet McColl’s aspiration was a hint of the future. The graving docks, long relegated to pieces of industrial archaeology, may come back to life in their original role. Remarkably, what has clung on at Saltercroft may have passed through post-Industrial and come out the other side. In 2020, New City Vision’s proposals were rethought by O’DonnellBrown and ZM Architecture as a working dry dock with a mixed use development behind it.

As I write, Govan Dry Dock Ltd. has been awarded a licence to re-open Dock No.1 as a ship repair facility, and the dock is currently surrounded with Heras fencing – which looks hopeful. The current proposal differs from the 2018 scheme in several respects, as the blocks of housing along Govan Road now form a continuous line and have reduced in number to around 300 units. There are already good precedents for the regeneration of sites along the banks of the Clyde. One of the best is Carrick Quay, an infill development designed by Davis Duncan for the Burrell Company in the late 1980’s. This block has four storeys of flats with two-storey penthouses above. It’s effectively a modern tenement, with nautical inspired masts and balconies lining the riverside elevation to Clyde Street. By contrast, the graving docks blocks turn their back on Govan Road, but they have the potential to achieve something different. Combining housing with a working ship repair yard is unusual. Several redundant docks have become marinas, but I can’t think of anywhere flats have been combined with a working dockyard.

That surely is a challenge, but toughest of all is to decide what “Clydeside” should mean in the 2020’s. With regeneration, the character of the Clyde has changed. When it was a working river, the water’s edge was lined with slipways, basins and quaysides. Most of the riverside was inaccessible, and gaps between the massive fabrication sheds on South Street and Govan Road offered only brief glimpses of the Clyde. Conversely, easy public access along the Clyde Walkway only emphasises the lack of shipbuilding, so a working dock at Govan would help to redress the balance. Fifteen years ago, I didn’t ask Tom Reid what he thought about the fate of Govan Graving Docks. I expect he would have been unsentimental about them, but would likely agree that returning the docks to their original use is the best solution of all.