The Lawns: Situation Vacant

21 Jan 2022

Urban Realm revisits a Gillespie Kidd & Coia masterpiece in the form of a halls of residence at the University of Hull which finds itself facing an uncertain future. What does its predicament say about the adaptive re-use of vacant buildings and the challenges of post-covid education? Words & photography by Mark Chalmers

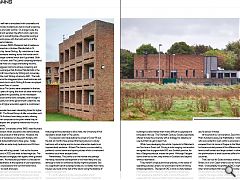

The Lawns is a former halls of residence at Cottingham, on the edge of Kingston-on-Hull in Yorkshire’s East Riding. It was designed by Gillespie Kidd & Coia in the 1960’s, marking their first major project south of the border. Since the University of Hull decided to concentrate everything on one campus in the city centre, The Lawns has been in search of a new use. In the 1960’s, Hull was a thriving port which lived off the riches of the Arctic fishery. Today, its industrial heart has been ripped out: Humber Street has been gentrified and some of the best working buildings along the River Hull, such as Clarence Mills, have been demolished. Others, such as the cluster of buildings around St Andrew’s Dock on the Humber, have been left to rot.

The poet Philip Larkin was university librarian at Hull. Larkin’s poetry explored the great themes of life and death, and he believed that poems preserve “a particular kind of experience, a feeling that you are the only one to have noticed something, something especially beautiful or sad or significant.” Larkin found significance in Hull and its surroundings, and he was quite familiar with Cottingham. In the 1960’s it was still a freestanding village, rather than the conjoined suburb it is today, but it retains a character typical of provincial England with 20th century houses built in the Queen Anne style, traditional pubs and leafy streets. It seems Philip Larkin was also familiar with The Lawns, although his opinions on the buildings aren’t recorded. In conversation with Isi Metzstein’s son Saul, I discovered that Larkin was involved in the University Council meetings about The Lawns. Isi observed that Larkin sat through the presentations, but mostly spent his time scribbling lines of poetry.

Did Gillespie Kidd & Coia, in Larkin’s words, discover how to surprise a hunger in oneself to be more serious? GKC still enjoy a high reputation in Scotland, thanks to the seriousness and rigour of their architecture. Yet that reputation is dominated by work for the Roman Catholic church: notably the seminary at St Peter’s Cardross and a sequence of churches. As a result, their other work has been over-shadowed. A second issue is the re-evaluation of Gillespie Kidd & Coia in the years since the practice was dissolved. The major publication on their work, published in 2007 after a retrospective at The Lighthouse, is in some respects a hagiography. Perhaps that’s a reaction to how the saga of St Peter’s affected their reputation, but the essays were written by people close to the practice and some veer close to being uncritical.

The irony is that GKC’s partners from the mid-1960’s through to the late-1980’s, Andy MacMillan and Isi Metzstein, were anything but uncritical about architecture. Their reputation among the current generation of architects was built on teaching: as professors of architecture they demanded a lot of students, and their criticism could be unsparing. I spectated during a crit at the Mac in the late 1990’s, an occasion when Isi had invited Andy along as a guest critic. They were sharp-eyed and quick-witted and, just like Larkin, you had the feeling they were the only ones in the room to have noticed the things worth noticing. So it’s daunting to visit The Lawns then try to assess it against Gillespie Kidd & Coia’s own standards.

The University of Hull began as a university college in the 1920’s and became a full-blown university in the 1950’s. By the 1960’s, it was growing fast and had run out of accommodation. The original masterplan called for 1,600 students and staff to be housed at The Lawns, in twelve halls arranged around a lake, but only six were built – and no lake. Each hall is a self-contained quadrangle (actually shaped like a Space Invader from the computer game) which consists of five sharply staggered blocks. Each block consists of three or four storeys of student bedsitter rooms, plus a single storey range housing the warden and tutors. There are five single rooms and two doubles on each storey, which share a kitchen and quaintly-named parlour. The Lawns made it into the best survey of British Modernism at the tail end of the 1960’s, Architecture in Britain Today by Michael Webb. “At ground level, by the entrance, is a common room and hobbies room. This progression of social units – nine rooms to each floor, 27 to each block, 135 in each hall – is characteristic of GKC’s concern with the human aspect of their buildings.”

You could argue that the organising principle of The Lawns is social unit, and while I couldn’t gather first-hand opinions, by all accounts the halls functioned well and were popular with students. Alongside the six halls is a Student Centre housing study, dining and recreational facilities: similar to the practice’s later work at Bonar Hall in Dundee, it consists of multi-level public spaces within inter-penetrating volumes. The construction of The Lawns is as simple as its plan is complex: load-bearing walls in brickwork. Each hall was conceived as part of the inhabited wall, and while the halls sit in a cluster of three, a pair, and one on its own, the overall impression is of an undulating plane of brick set above a sea of waving grass. The wall typology was later developed at GKC’s Robinson College to create a more complex effect. The inhabited wall here is articulated with crosswalls and balconies which provide modelling as well as visual screening, acoustic separation and solar control. On a larger scale, the halls are staggered and serrated: the effort which went into achieving that effect is something like a life painter posing a model in contrapposto pose, with the twist and turn of the torso creating dynamic balance.

The other well-known 1960’s Modernist hall of residence with a Scottish connection is Andrew Melville Halls in St Andrews, designed by James Stirling. By coincidence, it was also designed by someone working across the border and it was also part of a larger scheme which didn’t go ahead. Both stand on the edge of town, with The Lawns bordering farmland and Andrew Melville Halls on a ridge overlooking the links. Both utilise staggered rooms to achieve screening and privacy, and you could argue that Andrew Melville Halls is the most Gillespie Kidd & Coia scheme by Stirling and conversely, that The Lawns is the most Stirling scheme by GKC. The halls of residence also echo the staggered plans, inset balconies and internal planes of stock brick which Stirling & Gowan employed at their Ham Common Flats in London.

The first six halls at The Lawns were completed in the late 1960’s but despite years of trying, the other six were never built. The practice anticipated this possibility, so the masterplan with six halls and social centre looks complete, even though it isn’t. That was an early hint of the government’s dilemma: the limitless expansion of higher education against a constrained education budget. The last few decades have seen interesting times for higher education in the UK. The Russell Group of élite universities such as Edinburgh and St Andrews have deep pockets, allowing them to expand their campuses to the point where they’ve become land developers and property investors as much as educational institutions. The new “Redbrick” universities of the 1960’s were founded during a great expansion when education was democratised, and The Lawns was a product of that era too. However, the university-run halls of residence run like youth hostels, with spartan rooms and shared bathrooms have gone. Today, private providers offer en-suite study bedrooms and 24-hour gyms. This piece comes with a big caveat. I set out to discover how The Lawns stood in 2021, and what its fate might be. The University of Hull refused to engage; their agents were guarded when I spoke to them.

Architectural journalism is criticised for concentrating on aesthetics at the expense of user experience, but sometimes it’s impossible to find out first-hand how a building works for its client and users. The Lawns underwent refurbishment around a decade ago when some bedrooms were converted to kitchen and dining spaces, some double rooms made into singles and a number of bedrooms in one hall were converted to en-suite. But before that programme extended to all six halls, the University of Hull decided to divest itself of The Lawns. The decision was made before the onset of Covid-19, but the last 20 months have proved that being stuck in a study-bedroom with a laptop and no human interaction leads to an impoverished existence. At least The Lawns is surrounded by parkland, a social centre and sports pitches which its marooned residents could have escaped onto. Nevertheless, The Lawns is on the market and perhaps inevitably, residential development is the most likely end use, although a hotel or conference facility might be possible. But it’s a significant set of buildings to take on, no matter how many houses you build on the rest of the site to swing the balance of enabling development. It’s worth reflecting on the Listing paradox which I mentioned in the last issue. The Lawns is Grade II* listed (the equivalent of Category B) which simultaneously protects the buildings but also makes them more difficult to upgrade and bring back into use. The Twentieth Century Society reportedly offered to help the university with a strategy for adaptive re-use, but that has yet to bear fruit. While I was developing this article, I spoke to Isi Metzstein’s son Saul over a Zoom call.

During a wide-ranging conversation we agreed that to pigeonhole GKC as a Scottish practice, far less a Glasgow practice, misses the point. Although Glasgow claims them as its own, they worked in Scotland and beyond without reservation. They weren’t simply a provincial practice, in the sense of operating outside London, nor provincial in terms of having limited aspirations. The best of GKC’s work is a fully-realised architecture which follows its own relentless internal logic. From experience, that that’s costly in terms of hours and exasperating for the job architect since it means chasing down and resolving every last detail. Yet it’s essential to be rigorous if you’re serious-minded.

At the end of our conversation, Saul introduced me to Milan Kundera’s essay, Die Weltliteratur. Unlike Philip Larkin, who was content to work within a provincial context, Kundera escaped from his home in Prague to the West. Exiled in France, he became acutely aware of the difference between what he terms small context and large context: in other words, how the provincialism of small countries differs from that of large countries. That’s as true for Scots architects working in the rest of Britain, as it is for Czech writers such as Kundera living in the West. Undoubtedly, the profile of GKC is higher in Scotland (their small context) than south of the border. It always was. On the other hand, the fate of The Lawns is a test for how GKC is seen in the larger context of Britain as a whole, and indeed whether the wider world still notices something especially beautiful or sad or significant in their work.

|

|