Passivhaus: Shettleston First

23 Oct 2019

Glasgow’s east end has become the seat of an energy efficiency revolution with completion of the first passivhaus homes in the city. We investigate whether Cunningham House makes an airtight case for higher building standards. Photography by Tom Manley and Stephen Hosey.

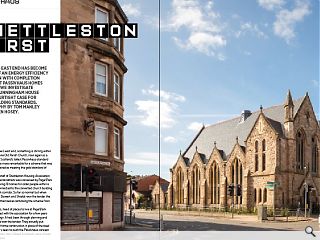

Deep within Glasgow’s east end, something is stirring within a reinvented Carntyne Old Parish Church, risen again as a Glasgow’s first and Scotland’s tallest Passivhaus-standard homes. A feat all the more remarkable for a scheme that was not originally conceived as meeting the gold standard of energy efficiency.

Delivered on behalf of Shettleston Housing Association the Shettleston Road landmark was conceived by Page\Park Architects as delivering 19 homes for older people within a new build tower, connected to the converted church building via a fully glazed link corridor. So far so normal but when building contractor Stewart and Shields won the tender the design team found themselves rethinking the scheme from the ground up.

Chris Simmonds, head of places to live at Page\Park recalled: “We worked with the association for a few years developing the design. It had been through planning and Stewart and Shields won the tender. They actually put forward the timber frame construction in place of the steel frame and were very keen to push the Passivhaus concept forward, which is when John Gilbert Architects were chosen as Passivhaus designer.

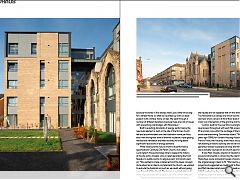

“Ideally they would have liked it to be all timber but because the tower is five storeys that’s just a little bit too big for a timber frame so what we’ve ended up with is a steel podium with a timber frame on top. We went through a number of different iterations because there are a lot of issues with preventing cold bridges with Passivhaus.”

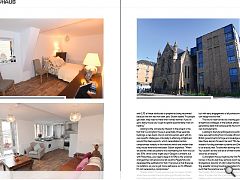

Built to exacting standards of energy performance the new build element is built on the site of the former church hall and accommodates one two-bedroom home per floor, each with the highest level of thermal insulation, triple glazing, mechanical ventilation and heat recovery to bring about significant reductions in energy demand.

While looking to the future in terms of performance specifications Carntyne Old Parish Church, now called Cunningham House also takes time to respect the history of the site with a modest cross in relief decorating the front façade in a subtle nod to its religious past. Simmonds went on: “We wanted to make a statement and the tower concept came about as an idea to complement the church, we wanted to extrude the footprint as much as we could without going over the roof of the church. The design is symmetrical on all three exposed sides with a square plan and corner windows.

“There’s a certain resonance with the church and the cross picks up the grid line of the main church in the middle of the façade and we repeated that on the other three facades. The horizontal is a canopy line which ties the building to the dormers which come in at third-floor level at the back. The cross is an intersection of the grid line and the canopy.”

Custom-built for the over-55’s Cunningham House has level access throughout with each flat accessible from a single lift and stair core within the curtilage of the historic church to avoid overshadowing. Simmonds added: “We did a project years ago (1996) for Gorbals Housing Association turning St Francis Friary into housing, there was a nice parallel to that in refurbishing a historic building and we’ve tried to create more generous lobbies so people can stop and have a chat and we’ve actually sourced an old church pew for people to sit on.”

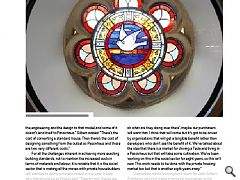

It was Mark Shields, director of Stewart and Shields, who proved instrumental in convincing the client to go down the Passivhaus route, somewhat naively choosing to simply adjust the original design intent to fit: “We tried to add value to the project and suggested we could build to Passivhaus standards and Matt decided what could be achieved and what couldn’t. I didn’t realise how big a challenge it was to bring an already designed project to compliance with building standards. If Passivhaus had been considered from the outset then it would have been a far easier building to construct. We tried to carry the engineering and the design to that model and some of it doesn’t lend itself to Passivhaus.” Gilbert added: “There’s the cost of converting a standard house. Then there’s the cost of designing something from the outset as Passivhaus and those are two very different costs.”

For all the challenges inherent in achieving more exacting building standards, not to mention the increased costs in terms of materials and labour, it is notable that it is the social sector that is making all the moves with private housebuilders still wedded to delivery models rooted in the past. Asked why that should be so Shields said: “Stewart and Shields are a family business; we’re the third generation and we have a social conscience. We believe we should be building better products than we are currently. It doesn’t sit well with me that we have expensive fuel bills in modern homes. That’s why I’m committing to doing this. It’s difficult to construct and there are more materials which are more expensive but at the end of the day you make a margin and I think we should be doing the right thing.”

Gilbert continued: “When you look across the whole of the UK there’s about 1,200 Passivhaus projects or houses and the vast majority of them are social housing. You can see that there is a trend now where you can see that people are going oh what are they doing over there’, maybe our purchasers will want that. I think that will come but it’s got to be driven by organisations that will get a tangible benefit rather than developers who don’t see the benefit of it. We’ve talked about the idea that there is a market for driving a Tesla and living in a Passivhaus but that will take some cultivation. We’ve been working on this in the social sector for eight years, so this isn’t new. This work needs to be done with the private housing market too but that is another eight years away.”

Shettleston marks a triumphant return for John Gilbert Architects who first made a name for themselves in this corner of the city 20 years ago at Glenalmond Street, a development of 16 highly sustainable homes drawing their heat from old coal mines. Gilbert said: “I think it’s important that this project is in Shettleston. It’s not just about Passivhaus but the regeneration of the church, this is part of a broader story. There’s a lot of innovation in this part of the city.”

At the heart of this low-energy crusade is not just a desire to minimise the carbon footprint of our homes but also to reduce high-levels of fuel poverty among the over-55’s, a contributing factor to rising eviction rates. Figures compiled by Shelter document 2,267 evictions by social landlords in 2017/18, a 44% increase on the equivalent figure from 2013/14 with 2,113 of these attributed to properties being recovered because the rent had not been paid. Gilbert added: “As people get older, they need to make their homes warmer. If you’ve got a leaky house you’ve got to spend exponentially more on heating.”

Adding to the complexity inherent in the project is the fact that Cunningham House is essentially three separate buildings, a new build, church and link section each with its own specific challenges, principally in attaining airtightness around the steel supports, which necessitated certain compromises notably in the windows which are smaller than they would otherwise have been. Gilbert explained: “When we did the initial calculations the overheating risk from the sun was 50%, which some might say in Glasgow is brilliant, but with Passivhaus, you need to keep it to 10% so the windows changed their dimensions but all credit to Page\Park who developed the aesthetics for that. The bonus is that there are no radiators, so you’ve got more wall space, so it’s different. It’s not necessarily a compromise.”

Shields added: “These guys have got to make it airtight when there are steel columns poking up through the floor. From the ground floor, we could see the guys getting better as they went from the 1st to the second. The guys had it nailed but with early engagement of all parties and stakeholders we can design around that.”

The church itself served as a testing ground for airtightness strategies in the earliest phases of the build, generating ideas that subsequently found their way into the new build elements.

Looking to the future Bridgestock points out that the team have secured funding from Innovate UK and the Scottish and British governments to forge a knowledge partnership to take these lessons forward. He said: “We have three years of research funding between ourselves and Stewart and Shields to do exactly that. To take that learning onto the next projects. You couldn’t do this and let all of that knowledge go. That would be a travesty.”

Cunningham House might be the first Passivhaus standard homes in the city but they certainly won’t be the last with Matt Bridgestock, director of John Gilbert Architects, reporting a ‘big appetite’ among housing associations for such properties such that the practice now has 320 Passivhaus homes on their books (250 in Glasgow), the majority still at the design stage. It is clear that this is just the tip of a much greater iceberg which promises to transform our expectations of what a home should be.

|

|