The Art of Drawing: Drawn Out

23 Oct 2019

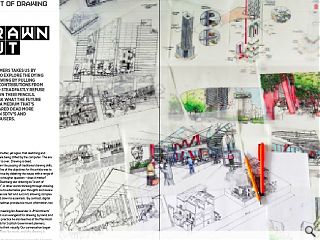

Mark Chalmers takes us by the hand to explore the dying art of drawing by pulling together contributions from those who steadfastly refuse to put down their pencils. Here we ask what the future holds for a medium that’s been declared dead more often than 3dtv’s and flared trousers.

So the greybeards mutter, yet again, that sketching and freehand drawing are being stifled by the computer. The era of pencil and paper is over. Drawing is dead.

Before we mourn the passing of traditional drawing skills, are they correct? One of the objectives for this article was to test whether that’s true by debating the issues with a range of architects, then ask a tougher question – does it matter?

The artist Saul Steinberg saw drawing as “a sort of reasoning on paper”, in other words thinking through drawing. Drawing enables you to externalise your thoughts and review the results. Sketches are fast and succinct, allowing complex ideas to be reduced down to essentials. By contrast, digital renderings can sometimes provide too much information, too early.

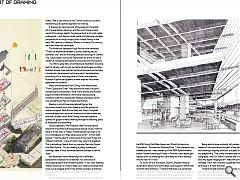

I started off by meeting Ian Alexander in JM Architects’ Glasgow studio. Ian is an evangelist for drawing by hand, and as well as his role in practice he also teaches at the Macintosh and has run tutorials for Scottish Government planners, encouraging them to think visually. Our conversation began with an overview of how Ian works, and why drawing is important to him.

Ian agrees that the design process begins with a drawing: he produces concept sketches very early in a project’s evolution. The fact he usually designs in section, he puts down to his education at the Mac under Andy MacMillan, and those drawings become a design tool. The sketch sections are impressionistic rather than realistic but as Ian explains, it’s important to illustrate activity by including people, dogs, cars and trees – rather than just drawing a piece of autonomous architecture.

“My process is that I do different sketches for different purposes: quick communication with colleagues, contemplation, project concept, project-specific 3D perspective sketches, and travel – both observing things and on reflection. It’s really all about different ways of communicating.”

He’s conscious of working in a tradition which includes Steven Holl’s figurative drawings, Cedric Price’s sparely-drawn outlines, and the perspectives of James Stirling projects which were drawn by Leon Krier in the style of Le Corbusier’s little sketches. Each perspectivist develops the skill of knowing just how much to reveal at each stage, and understanding the power of suggestion contained in the thickness of a quavering line.

Ian noted that he delays the point of scanning a hand-drawn sketch and converting it into a “hybrid” drawing – whereas younger architects go digital much more quickly. I’ve also observed how recent graduates go straight from brain to machine, and there’s even a parallel with my young nephews in Oslo, who absorb themselves in designing imaginary cities using Minecraft, rather than with crayons and paper.

Despite the practiced simplicity of Ian’s line drawings, they hide lots of deliberation about process and technique. How will the drawing reproduce? Ian draws with this in mind, and while he has experimented with pencil and wash, he usually uses an ink fineliner with the knowledge that the linework will tighten up as it’s reduced in scale.

I asked about the role of sketchbook: in common with many architects, he buys different sizes of Moleskine. The small ones are used for concept sketches, the larger ones for more finished work. “The thing is making time to draw – discipline is needed to do your own work,” and the sketchbook facilitates this by being available all the time, anywhere.

I’m dismayed when there are no sketchbooks on display at degree shows: Ian noted that keeping one is encouraged at the Mac, and students also create design journals into which sketches and development ideas are bound. That well-recorded thinking is another aspect of the discipline of drawing.

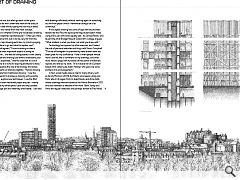

After our discussion, I walked back through the Merchant City and reflected on an architect who uses hand drawing in a completely different way to Ian Alexander: Mikkel Frost of CEBRA Architects sees his architectural cartoons as “a wordless manifesto” and draws a colourful architectural graphic of each project, post-facto, once the building is complete.

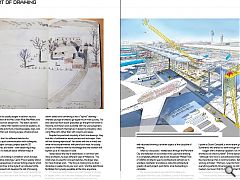

My next conversation was with Emma Gibb, who graduated from the Scott Sutherland School in Aberdeen five years ago and is now an architectural illustrator and associate partner with Foster + Partners in London. Shortly afterwards, I spoke to Stuart Campbell, a more recent graduate from Scott Sutherland who shares his work through an Instagram page.

I began with a rhetorical question: Is it important that architects can draw by hand? Emma replied, “I think yes – although I am not in a conventional architect’s role, I see the importance it has in communication. Before I started working at Foster + Partners, I used to think I had to draw everything perfectly to be honest to my skill and my choice of medium, but now I find it’s more important that my drawings communicate a story or idea.”

“I draw both for pleasure and to think and design. Sometimes I use it as a tool to warm up an idea, or even just to begin the day. I sometimes develop this quick sketch into a more detailed one, but often go back to the quick and dirty sketch, as for me it often tells more of the story or communicates the idea without going into too much detail, which can distract the viewer from the main concept.”

I was interested in whether Emma pre-visualised a drawing in her mind, or just sketched spontaneously? “Often yes I have an idea of its outcome first, but it can be very far from the finished result – as I am drawing each line, my mind is pinging ideas around of where to go and what to explain next.”

Stuart Campbell agreed, “Communicating an idea is probably the single most important aspect of being an architect or designer … the real skill being tested is how clearly you express yourself and making sure others understand your design intent.” He expanded, “I like the idea that it’s a skill that’s become more of a niche for aspiring architects to have.”

I was keen to explore the role of technology and asked Emma Gibb’s thoughts on drawing digitally. “Hybrid drawing to me is not separate from traditional drawing – I use the same skills I have learnt to produce a drawing with possibly a different style or explore new techniques. I use the iPad Pro more and more over traditional paper and pen – mainly because I can have my whole pencil case and any possible canvas size in a single pen and relatively small tablet. I can also edit drawings efficiently without starting again or scratching out ink from paper (which I remember doing a lot of at university).”

If the digital drawing has come of age with touchscreen tablets like the iPad, the apocryphal fag packet sketch made using a Biro pen still works equally well. As Samuel Rabin, who taught the artist Bridget Riley at Goldsmith’s College, argued, “What matters is what you draw, not what you draw with.”

Technology has opened up other avenues, and I raised the role of personal websites and blogs with Stuart Campbell. “The use of Instagram to promote my hand drawn work has been great for my confidence. I love it when people whose work I admire, like or comment on my drawings, and even more when a page with hundreds of thousands of followers reposts and shares my work. I’m a massive fan of a London-based artist called Luke Adam Hawker who gave me some pointers and encouragement.”

In fact, social media plays a role for many others, such as Sandy Morrison of HTA Architects who keeps a blog and Flickr album of pages from his sketchbook, and Anna Gibb whose drawings were exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2012 and also maintains a website of her work. Both Sandy and Anna are regular sketchers and perhaps adhere to Paul Klee’s motto, “Not a day without a line”, which he saw as crucial to maintaining a disciplined approach to drawing.

If drawing by hand consists of two aspects: the public art of presentation drawings, and the much more private world of the design sketch, the perspectivist is its most visible protagonist. Look behind social media and there are countless perspectivists to study, ranging from Joseph Gandy in the early 19th century to Lebbeus Woods in the early 21st century, each with their own technique.

The American delineator Hugh Ferriss once remarked, “There is a difference between a correct drawing and an authentic one”, and his brooding charcoal drawings of Gotham City’s skyscrapers during the Depression era prove he was a master at conveying atmosphere using only tone and texture.

The 1960’s generation of architectural illustrators including Helmut Jacoby, with his pen and airbrush technique, and Paul Rudolph whose cross-hatched sectional perspectives became a trademark, developed a technique which dematerialises everything into a stunning pattern of lines and shadows. Rudolph in particular appears to have inspired the current generation of students.

Many will remember Frank Ching, from whose book “Form, Space and Order” they learned the basics of pencil rendering and composition, while more recently the Russian paper architects Brodsky & Utkin have inspired young architects with their obsessively-detailed cityscapes which owe something to Mervyn Peake and Piranesi.

Bearing in mind those inspirational figures, the discussion moved on to how drawing could be passed on and encouraged. Both Emma Gibb and Stuart Campbell acknowledged how important mentors and role models are, and both studied under Alan Dunlop, who has helped to spread the gospel of hand drawing through his teaching posts at Aberdeen and elsewhere.

Stuart explained, “My Professor (Alan Dunlop) spoke about the importance of being proud enough of your work to hang it on the wall, or make a model beautiful enough to sit on a mantelpiece as if they were pieces of art.” Emma Gibb agreed: “I like the idea of continuously trying new things and different methods – some of which may never be repeated! This is something I learnt from my mentors Narinder Sagoo and Alan Dunlop – I’m not creating a pretty drawing for drawing’s sake, it must communicate the concept or tell the story.”

Ian Alexander views mentoring from a different perspective: because he is a teacher, he’s conscious of encouraging talent and transferring skills. In this case, drawing matters because it’s a way to keep your creative faculties alive once you’re bogged down in the prosaic business of practice. Being disciplined about drawing helps to reinforce a love of architecture.

Emma Gibb also flagged the role of drawing competitions and awards which have proliferated in recent years, including the RIAS Andy MacMillan Award and World Architecture Foundation - Architecture Drawing Prize. “I found awards very beneficial to me, I was runner-up in the RIBA Eyeline Award before I started working at Foster + Partners, that helped gain exposure for my drawings and ultimately led me to develop into the role I’m in now.”

To round off our discussion, Stuart Campbell made an observation about how technology could support, rather than diminish hand drawing – “The fact that there is a connected community of artists, designers and craftspeople using social media to inspire one another and share experiences is one of the main reasons that there’s been increased appreciation of drawing by hand.”

Being able to draw evidently still matters, both as means of communication and part of the design discipline, and drawing’s ongoing evolution is a good illustration of our adaptability. That’s why movable type didn’t kill off calligraphy, why Fox Talbot’s camera didn’t destroy painting, and why digital imaging didn’t make film photography obsolete. Each new invention supplanted then pushed an old technique in a fresh direction.

I’ll leave the last word to Ian Alexander, who observed that the life of a writer is usually much better documented than that of an architect. As a result, the discipline of drawing by hand is often undervalued, possibly because it’s rarely written about. Hopefully this article goes a little way towards rectifying that.

|

|