Ashtree Road: Dark Arts

21 Oct 2019

Pollokshaws is in the throes of radical transformation as a new generation of architects step into resolve the mistakes of the past. At Ashtree Road new kid on the block Graeme Nicholls Architects are leading that charge with their first major scheme but will it stand the test of time? Urban Realm paid a visit to see if these homes can weave some magic within a tight-knit area.

Weaving its way through the heart of a reimagined Pollokshaws a modest housing scheme is seeking to summon the healing power of architecture to streets fragmented by urban renewal, but has it struck black gold?

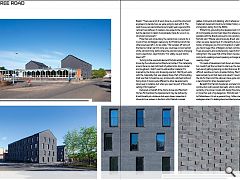

Ashtree Road is the first major scheme completed by Graeme Nicholls Architects since their formation in the summer of 2016 and it stands as a statement of intent both for the practice itself and for the ongoing urban renewal of Pollokshaws, now rapidly transforming amid the ruins of Dorward Matheson Gleave’s Shawbridge tower block quartet. Countering this lost Modernism with buildings on a more domestic scale Graeme Nicholls hasn’t laid the ghost of Corbusier fully to rest, saying: “The whole building is based on human proportions and Corbusier’s Modulor Man which is based on human scale and anthropometrics. The windows, for example, are 1.1m wide and 1.2m high, the same scale as Vitruvian Man. Everything in the building is derived from that base scale.”

Taking the form of 24 two-bedroom flats divided between a ‘tenement’ block and a shorter offset neighbour likened to a ‘villa’ the homes are arranged as a wedge bounded by surrounding streets and anchored by an imposing red brick wall, all that remains of a 1920s wash house. Nicholls told Urban Realm: “There was a lot of work done by us and the structural engineers to decide how we were going to deal with it. The wash house was demolished around eight years ago and this remnant was leftover. It creates a nice edge to the courtyard but the decision to retain it was already made for us as it is a structural component.”

More than just a boundary the wall acts as a canvas for a mural of two old Belgian weavers by Art Pistol but which has otherwise been left in its raw state. “We’ve taken off some of the tiles but when we first came you could see a cross-section of the old swimming baths where the pool and sauna changing rooms used to be”, says Nicholls. “For safety, we just had to take it off.”

Turning to the new build element Nicholls added: “I was driven by the cultural and architectural context. The materiality around here is a real mishmash of yellow brick, stone, render and roughcast. I didn’t want to add another material. It’s inspired by the library and shopping precinct. I felt I’d just work with the materiality that was already there. Part of the building brief was that it should be very simple with a pitched roof and facing brick. It looks quite different to other developments when seen in isolation but when you see it as part of the urban setting it fits together.”

Delivered on behalf of the Home Group and Merchant Homes Partnerships the development may be defined by it bold tonality at a distance but upon closer inspection it shows its true colours in the form of its Flemish inspired gables, brickwork and detailing which reference not the city’s trademark tenement stock but a hidden history of Belgian immigration dating from the 1800s.

While firmly grounding the development in the rich history of its immediate environment does this reference also carry parallels with the Brexit paroxysms now wracking the country? Nicholls said: “Maybe subconsciously, Brexit was kicking off when we were designing it. It’s interesting if you look at the history of Glasgow you think immigration is relatively new but you had a huge influx of Belgian workers coming in the 1800s. There are poems and contemporary reports from the time calling them ‘the queer folk of the Shaws’ because there is this community walking around speaking a strange language and wearing clogs.”

“A couple of developers had shown an interest previously but couldn’t get the numbers to stack up, the reputation I had was of getting planning on sites that are a little more difficult, sensitive or had a troubled history. Merchant Homes approached me on that basis and asked if I could have a look at the site for them and the planners have gone onto endorse it as a benchmark for other developments.”

Beneath this Flemish façade lies a simple timber kit construction with precast stairwells, which combines the certainty of a proven model with design flourishes resulting in more than just a ‘big beige box’. Nicholls said: “It relates to Pollokshaws, it’s not a generic thing. I often make food analogies when I’m talking about architecture because I also like cooking. It’s not stir-fried architecture with everything thrown on the pan, I try to make it slow-cooked, so the flavour comes out over a longer development period.”

This desire for depth inspired several subtle touches beyond the black brick and Flemish gables and rewards a closer look: “Nicholls said: “We’ve got the Flemish bond at ground level with an outer skin of alternate cut bricks although historically it would have been double thickness and tied together for integrity. We’ve also got weaving motifs in the paving. I wanted to create something which you appreciate more when you see it in the flesh so it’s not all image-based. When you see photos of the balustrades straight on you don’t appreciate the subtlety but when you’re on-site and move around you get an interesting visual effect like the flik flak of a loom. These are people’s homes and you want them to feel they will last as long as they do, rather than something ephemeral which will blow away in the wind.”

Attention to detail can only go so far however with a narrow eaves edge falling foul of buildability while concessions to day to day life have seen satellite dishes and security alarms sprout from the façade. While inconvenient Nicholls is philosophical, saying: “I think it’s ok, it’s a rear courtyard where you would have the bins and gas risers. We thought to paint everything black just to blend in.”

Each of the 70sq metre two-bed flats is the ‘same but different’ utilising just three distinct flat types, as Nicholls explained: “There’s not a set family model for occupying the houses, there can be different living arrangements with different types of people sharing. The living room could be used as a bedroom and workspace or one of the bedrooms as a living space. The way the flats are serviced there are two workstations in each flat. It’s not customisable in terms of carpets and surfaces its more how you occupy the spaces. The ground floor flats are wheelchair adaptable as well so if someone with different accessibility needs moves in the flat can be easily adapted with a wet room if needed.”

A contentious site history can spell trouble for any architect but by embracing a rich and chequered history these homes show that Pollokshaws can look to the future with a new confidence.

|

|