Northern Powerhouse: Fast Track

16 Jan 2019

Numerous visions to rebalance the UK have focussed on unifying competing northern English towns and cities. Do a new generation of high speed rail links show such goals are now in the right track? Architect Ian Banks investigate

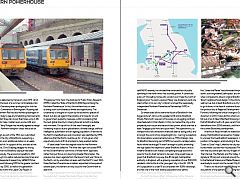

Six months on from the untimely passing of the late, great Will Alsop in May, his vision for a fluid Trans-Pennine city, is up for debate again – albeit this time, from the pure transport perspective of devolving rail infrastructure: December 2018 saw the Government deadline for Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) to submit its Strategic Outline Business Case to the Secretary of State for Transport. In this, Transport for the North (TfN), are updating their plans for ‘High Speed 3’ (HS3), better known as ‘Crossrail for the North’. This of course is linked to the launch four years earlier in Manchester, where Coalition Chancellor, George Osborne, first proposed his Northern Powerhouse ‘economies of agglomeration’. His vision included a high-speed rail link connecting Leeds and Manchester.

Back in 2004, Alsop’s own pan-northern vision was for a longer Liverpool to Hull conurbation spread over 100 miles and 20 miles wide. His ideas featured as part of his Channel 4 series Supercities UK, and was one of three extraordinary linear cities he saw as emerging along the nations motorways and highways. “They’re the future” he said by way of introduction, “and I have plans to make them even better”. As such, the case for his Great Northern SuperCity called ‘Coast-to-Coast’ was expanded upon in an exhibition and book launch at Urbis, (then) Museum of Urban Life in Manchester the same year. It coincided with the Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott’s Urban Summit being in town, with his call for a “paradigm shift” as part of New Labour’s Northern Way strategy (and precursor to the Northern Powerhouse).

On the surface, Alsop’s utopian thinking looked to pay allegiance to a linear city concept first developed by Arturo Soria y Mata in Spain during the 19th century. Soria’s city created a core infrastructure to enable a process of expansion that merged one growing city node to the next over time. This was the core thinking behind Coast-to-Coast, with its thread of transport and rural parks running through.

No single city along this route should dominate any other though believed Alsop: “what we are after is a chain of singularly extraordinary points all the way from the Mersey to the Humber”.

As such, he saw Coast-to-Coast as being one big landscape of different characters, events and activity. Each city offered a different experience: “A Friday night out in Liverpool; A Sunday afternoon in Bradford; A Wednesday in Hull” he imagined idly. Remarkably, his ideology was also backed up by a string of actual commissioned feasibilities over a 7-year golden period in the north which resulted in ambitious proposals spanning across the Pennines. These ranged widely from a Liverpool 4th Grace (2002, aka ‘The Cloud’ & ‘Diamond Knuckleduster’); to a Manchester residential block (2009, aka ‘Chips’); a Halifax Piece Hall development (2003, aka ‘The Silo’); the Barnsley Masterplan (2002, aka ‘Barnsley Halo’ & ‘Tuscan Hill Town’); and finally Bradford Masterplan (2003, including the ‘Mirrorpool’ aka ‘Puddle in the Park’). With the exception of the small portion of Chips wrapped-up for Urban Splash, the only other northern project of his to move forward to close realisation was the pale imitation of his Bradford Masterplan – and at realisation, even this was without Alsop at the helm.

So, after Hull was crowned City of Culture in 2017 and following-on from Liverpool as Capital of Culture in 2008, might Alsop’s vision of an agglomerated Coast-to-Coast be worth a revisit? Whilst the jury remains out on that, one thing is clear, which is for it to ever stand a chance, then a fully integrated transport infrastructure would need to be put in place first. This would also need to be one that mitigated against the winter ravages of the high Pennine weather on road and rail.

Contrast such idealised thinking with a pragmatic reality check from today: The start of December 2018 saw a 39th day of strike action on Northern Rail networks starting, linked to the threat to guards as defended by transport union RMT. All of this has happened on the back of a summer rail timetable crisis that had the Transport Secretary even apologising for it at the October Conservative Conference in Birmingham. Rubbing salt into these wounds, Northern Rail has also warned passengers in the north they are not likely to see any timetabling improvements until May, despite the fact they plan to put their fares up by 3.2% in the new year. Then to make matters even worse, HS2 and Crossrail chairman Sir Terry Morgan has recently agreed to resign ‘by common consent’. Northern transport chaos would be an understatement.

Still resolute though, as part of the TfN’s own submitted business case for NPR, the City of Bradford is supporting a case for its late inclusion as an additional station on a Leeds-Manchester high-speed link. In support of this, and also at the recent party conference, Chris Grayling pledged his strong and personal commitment to Bradford, saying it had been “woefully served” previously. The economic benefits to HS3 seem compelling enough: As well as reduced journey times and increased capacity, independent research by GENECON has quoted a significant boost following NPR to the greater northern economy of £15 billion by 2060, as well as the generation of 15,000 additional jobs within the Leeds City Region. A consortium of Yorkshire council leaders are also currently advocating for a ‘One Yorkshire’ devolution deal that delivers a £30bn-a-year boost to both region and UK.

Tempering these northern expectations however, December 2018 also saw publication of the annual report from the UK ‘Progressive Think Tank’, the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). Called the ‘State of the North 2018: Reprioritising the Northern Powerhouse’. In this, the northern focus is seen as being both a simultaneous threat and opportunity: The uncertainty is brought on in part by the economic spectre of Brexit, but also set against the paradox of a hope for an end to government austerity measures, whilst considering that the next global downturn is being forecast as both inevitable and imminent. On top of this (if that wasn’t enough), are increasing impacts due to globalisation, climate change, artificial intelligence, automation and an ageing population. A real test to the North’s steadfastness and innovation was identified by IPPR, albeit one that the North could be up for - if only given a fair opportunity and a shift of emphasis to help enable it better.

A ‘clear break’ from the original vision for the Northern Powerhouse was called for. The time was right concluded IPPR, for the Government to commit to a ‘whole North’ approach, rather than just focus on a booming Greater Manchester. The previous top-down agenda from the Government was “done to the North, not by, and often not even with the North” it said. With three Northern Powerhouse ministers appointed in the space of several years, this remains a tricky issue for the Government to deal with.

A direct descendant from the ‘Cities and Local Government Devolution Act’, Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham remains an advocate for the Northern Powerhouse and has previously described it as being potentially a ‘dawn of a new era’, and not just for the city region. Despite this, interviewed on talkRADIO recently, he criticised the continued lack of public spending in the north which has stunted growth. A continued policy of “Shovelling money into London won’t help the north of England grow” he said. Liverpool Mayor Joe Anderson went one step further in his own city’s criticism and quit the supposedly independent Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) in December.

So where does all this leave the future of Bradford in the bigger picture? John Lord’s excellent 2016 article ‘Bradford: Woolly Mammoth’ was part of his series on struggling northern cities featured in Urban Realm. In this, he marked the city as the perpetual poor cousin and second-class power, albeit one that at least “engages your mind and your heart”. Not quite extinct, its transport and rail connections were still seen as being pitiful, and amongst the worst of any large English city - barring Sunderland. His observations would certainly back up TfN’s strategic case for Bradford becoming part of NPR, but would a rail deprivation factor alone be enough? It wasn’t enough to justify extending the high speed line beyond to Leeds-Bradford Airport, and so whether Bradford can make a compelling enough economic case for the city itself remains to be seen. One would hope so given that Bradford is anyway the 4th largest metropolitan authority in England, with a growing population of over 500,000 residents. Add to this it is the ‘youngest’ city in the UK (23.7% of it’s population is under 16 as compared with 18.8% nationally), and has one of the most diverse populations too (ethnic minorities making up 36% of the total).

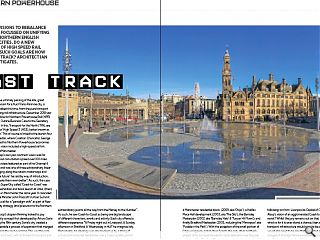

So might the ‘Alsop-effect’ still have any further influence on Bradford after his death? In reviewing one of It’s few urban design successes of modern times, the City Park, John Lord cited planner Adrian Jones, from his 2016 ‘Cities of the North’ book. In this, ‘Jones the Planer’ had dismissed the project as a dumbed-down, cost-engineered ‘palimpsest’ and entertainments plaza, when compared to Alsop’s original Bradford Masterplan and ‘Bowl’ neighbourhood design. In the strictest terms, this might well be true, but at least Bradford as a city has had the boldness to go it alone, in the face of a national funding rejection and the political loss of Regional Development Agency Yorkshire Forward, following the critical change to Government post downturn in 2010. It also did this whilst surviving the political fall-out of an ill-fated Westfield Shopping Centre development that left Bradford with a 9-year vacant ‘hole-in-the-ground’ post demolitions from 2006 onwards, until the eventual completion of the current Broadway development.

In terms of Alsop himself, his stated starting point was always that Bradford remained too ‘hidden’. This bred his desire to uncover the true Bradford ‘experience’, starting with its position in the region, and including at the centre of his perceived ‘Coast to Coast’ map. Linked to the city topography and it’s buried water courses was his proposed ‘Park at the Heart’, with the city centre split into four fingers known as The Bowl, The Channel, The Markets and The Valley. Within the Bowl, its signature ‘Mirrorpool’ wrapped around the City Hall, adjacent to the National Science and Media Museum, and designs were eventually to morph into the current City Park.

There is no record of how Will Alsop might have viewed accusations of any perceived dumbing-down of his Bradford masterplan. What records that do exist seem to indicate that he did at least positively acknowledge the boldness of the creative risk that Bradford council took with City Park, and the positive catalyst the resultant meeting place once built had on the wellbeing of the people of Bradford.

Historically, the conversion of Alsop’s Bowl designs had come first via Urbed’s City Centre Design Guide and then Arup’s Neighbourhood Development Framework. Thereafter, a 2006 design competition was won to lead on the delivery of a simpler, more achievable scheme, by landscape architects Gillespies. Despite their proposals submitted to the Big Lottery Fund being rejected, happily Bradford Council (very narrowly) elected to proceed and build anyway. A year after the 2012 opening, the Academy of Urbanism in awarding the City Park a ‘Great Place Award’, stated that Bradford people were still learning how to use their space by exploring its possibilities.

Initially, as self-styled ‘Bradford Virgin’, Alsop had stated “I wish Bradford well” in his opening Masterplan introduction. Fifteen years on from the launch of that, there were over 15 million visits made to the City Park in its first 4 years alone; a reported £1.3 m boost to the city economy in the first 6 months; and a multitude of urban design awards since received. Beyond these typical quality indicators, the 2014 report ‘The Great Meeting Place : A Study of Bradford’s City Park’ by the University of Bradford and Centre for Applied Social Research, also celebrated the pure public popularity and inclusivity achieved by the space.

Eulogising Will Alsop, in their official obituary, the Architects Journal described him as being able to ‘conceive an imaginative field of objects, possibilities and emotions in which architecture could come into being as a frame for enjoyment and fulfilment’. It also quoted him as once stating “I like people and I hope it shows”. This amicable, empathetic spirit was at the very heart of the man and his design philosophy.

The same public joy for the City Park shines through today also, as does the fact that whilst the design may indeed be a far more simplified abstraction (literally in terms of the aquifer fed mirrorpool), the creative homage owed to the Alsop original remains clear. Regardless of Bradford’s new rail infrastructure ever being granted as part of HS3, or his conceptual linear Coast-to-Coast ever being realised, this human legacy will remain his most significant gift to a city’s ongoing self-discovery and wellbeing.

Of Bradford he said: “The point is, they have done it. It’s a very important focus for the city, it can become a meeting place for the people. It has an inherent beauty, a sense of calm and peace”, at the 2013 launch of City Park. “I’m very proud of it” he added, and then laughed: “I can’t think of any other city with a puddle in it!”

His playful irreverence often disguised his more serious undertones, but it could never diminish the uniqueness or integrity of his bold vision. The next big step for Bradford is to try to gain approval for a new station on the important HS3 link. City Park may appear an urban design flippancy to some purists, and is arguably a watered-down version of an original concept at that, but it has undoubtedly helped Bradford stand out and gain confidence to position itself far more equally within his virtual Great Northern SuperCity.

|

|