Campbeltown Picture House: In The Picture

27 Jul 2018

Campbeltown’s atmospheric picture house has thrilled audiences for over a century but had latterly descended into a horror show of its own making. Now extensively refurbished it is a picture of health once more but what can it tell us of wider rebirth and renewal? Are you sitting comfortably? Then let us begin. Photography by Keith Hunter

Given Campbeltown’s remoteness its dilapidated grade A listed picture house can be said to have reached the end of the road, in all senses of the word. Its isolation has however spurred an unprecedented refurbishment project, designed to breathe new life into the town (and spare cinephiles a 266-mile round trip to Glasgow). Urban Realm catches up with some of those involved to find out how a zombie cinema has been transformed from a B-movie horror to A-list glamour, making this once silent cinema the talk of the town.

Prominently positioned on the esplanade the fabric of the building had deteriorated badly, necessitating extensive restoration and repair to bring it into the 21st century. Faced with this task one of the first orders of business was deciding what era to prioritise. Explaining their approach project architect Stefanie Fischer of Burrell Foley Fischer told Urban Realm:” This is an issue that crops up quite a lot in conservation as in what period do you go back to. In terms of cinema history the highest significance of that auditorium is as a representation of atmospheric cinema. That is more significant than how it was as originally constructed in 1913 to designs by Albert Gardner.

“In 1934, the auditorium was changed to an Atmospheric-style interior. That coincided with the period when sound was introduced and quite a lot of 1930’s cinemas are of this type. One of the common features of these interiors was the representation of a street scene.”

At Campbeltown this takes the form of two little houses at either side of the proscenium arch, with walls painted like masonry sitting below a barrel shaped room with a painted sky-blue ceiling. In an era of rapid technological change this harked back to an earlier, simpler, age of cinema as Fischer said: “The idea was when you were in the cinema you were part of a collective experience within a fantasy street scene. As a cinema architect I found that an interesting motif because of the emergence of cinema on the street. In its earliest days cinema was screened in tents off market places.”

One vestige from the era of silent movies is that the cinema is naturally ventilated through the roof, with no mechanical ventilation provided. An unintended consequence of this was that you could hear the soundtrack outside the auditorium and given the neighbouring tenements, a situation which was just not tenable. Fischer added: “Part of the business plan for the reopened picture house was that it screen all day and on weekends but you can’t have noise disturbance in a residential area. Mechanical ventilation had to be introduced and you have to achieve a very high number of air changes because the auditorium is used for back to back screening throughout the day. It can get very hot and depleted in terms of Co2 build up. The integration of supply and extract had to be carefully considered.”

This earliest form of pop-up cinema might provide a romantic canvas but there is still a demand for a permanent physical presence with more concrete social benefits, but the surviving cinema didn’t necessarily lend itself to these requirements. Fischer continued: ”For the building to remain in use as a cinema it had to meet expectations of modern audiences and operators. It had to be upgraded and the scheme was to upgrade it in a way which celebrates what is interesting about it architecturally and historically while meeting modern expectations of comfort.”

Picking up on the wider history of UK cinema design Bruce Peter, professor of design history at The Glasgow School of Art told Urban Realm: “Atmospheric-style cinemas were once commonplace but it’s unusual to see one on such a small scale, it’s rather charming in its cute/kitsch way. Every small town had one cinema or even two, there was one a little further along Campbeltown’s promenade called the Rex which was demolished. They were very attractive development plots in the sixties and seventies. It’s amazing when you look nationwide and see how many cinemas were replaced by petrol stations and supermarkets.

“Cinemas built in the 1930s were a little bit bigger and used a lot of asbestos in their construction. Gardner was one of the worst offenders, facing entire auditoriums in asbestos cement slabs as if it were a factory behind the showy façade. Events such as the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Bellahouston park were entirely faced in textured asbestos cement that was then spray-painted.”

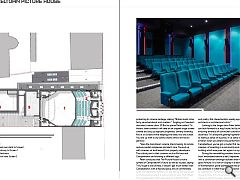

“When Campbeltown opened it had up to 700 seats, we’ve reduced the seat count to closer to 200”, explains Fischer, “that enables far more comfortable seats to be put in with generous leg room. We were more limited in what we could do in the stalls than on the balcony without altering the interior to an unacceptable degree. Because of the architectural detailing of the walls a lot of thought had to be given to the positioning of speakers to get excellent sound quality without spoiling features of the interior and detracting from the scenery.”

Fortunately, Campbeltown is solidly built and more manageable in terms of its heating bills – two key considerations which have helped to make it a rare survivor. “Campbeltown survived because there was no competition and few rival attractions and they cut costs until they come to a point of reckoning when they need to buy a new projector and the seats are getting worn so it just shuts”, says Peter.

Part and parcel of running a modern public venue is inclusivity, ensuring equal access for all irrespective of how able-bodied or not you may be. Explaining how this was achieved Fischer said: “The entrance used to be up some steps, you can’t alter that because there is no room to introduce a ramp or alter the appearance of the façade. What we’ve done is to create a new accessible entrance on an outside passage at the back. We created a big opening in the wall to create a single sales point which is continuous with a café/bar that has views out across the harbour.

“Ease of operation is also essential because you don’t want to be staffing the building during quiet periods. A second screen has been built in the yard to the rear at the end of this linear foyer. That’s essential to the project so that they can screen specialist films without taking over the main auditorium. It’s part of the music school and event screenings such as ballet, dance and exhibition openings and schools or hired by local businesses.

“Places like Campbelltown to be a cultural and social hub in order to be sustainable. It meant a lot to the community when it first opened, local families contributed to the original picture house. It was independently owned up until the 1960s when it became the first community business to be established in Scotland. If you go on the community Facebook page you can see what the cinema means to people not just in Campbeltown but across the Kintyre peninsula.

Commenting on the scale of intervention required to bring the cinema up to a contemporary spec Peter continued: “The issue for me is not that people have to modify things and you can’t do a perfect restoration. It’s the level of finesse and intelligence with which it is done. You’re either building it in a way that doesn’t jar or you find some way of encoding a delineation of what’s original fabric.”

Being half-Danish Peter brings a Scandinavian perspective to the UK’s generally dismal record of protecting its cinema heritage, stating: “Britain tends to be fairly parochial about such matters.” Singling out Sweden’s dominant cinema chain SF Bio for praise Peter added: “In historic town centres it will take on an original single screen cinema and buy up adjacent properties, cleverly inserting five or six screens while keeping one really nice old screen. You end up with a city centre cinema which still has its glamour.

“Here the mainstream cinema chains belong to remote venture capital companies and don’t care. You end up with cinemas on land leased from property developers. The critical point is that cinemas such as Bo’ness and Campbeltown are following a different logic.”

Peter concludes that The Picture House is now a symbol of Campbeltown’s future as well as its past, saying: “You’ve got a wet climate, it doesn’t get much wetter than Campbeltown, with a flexible space, lots of comfortable seats and adjustable lighting. It’s like having the equivalent of a banqueting suite at a luxury hotel on your High Street. It’s a seaside place that’s also been an industrial town that has a building that’s really quite jovial, fun, joyous and pretty. Not characteristics usually appreciated by architects or architectural critics.”

Looking to the longer-term Peter believes that cinemas can look forward to a rosy future, led by the public’s enduring embrace of communal cultural activity. Peter observed: “It’s everyone getting frightened or laughing or feeling a sense of injustice. It’s a sense of shared emotion when you attend one performance together. In Campbeltown you’ve got a model. Not necessarily for cinemas, of investing in a community and restoring a key building which everyone can agree is a symbol of the place.

During the remodelling workers discovered a ‘lucky boot’ embedded behind a wall, deposited in accordance with a convention amongst builders that this would bring good fortune. It is now on display in a dedicated museum in Northampton, proof perhaps that the present custodians are confident in what they have delivered without recourse to superstition. Campbeltown Picture House is no mere museum then, if it’s to survive at all it must embrace the future as well as the past, placing it on a firm footing for the 21st century.

|

|