Drone Photography: Rise of the Machines

19 Oct 2015

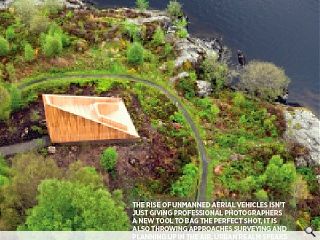

The rise of unmanned aerial vehicles isn’t just giving professional photographers a new tool to bag the perfect shot, it is also throwing approaches surveying and planning up in the air. Urban Realm speaks to those in the know to see if the sky really is the limit for drones.

Used for everything from agricultural and industrial surveying to broadcast footage aerial drones are increasingly relied upon in the construction industry to reach places where others cannot. This process is being given a helping hand by new software such as Pix4d which allows 3d modelling of terrain to be undertaken from geo-referenced still photographs. Such data can be used to build elevation maps enabling quantity surveyors to accurately assess volume and the overlay of 3d models for to aid planning applications. This technique is also useful in flood prevention.

More prosaically the system can also be employed to provide indicative high rise views and produce planning photos, marketing, time lapses, fly through video, surveying, 3d model creation and navigating hazardous environments. Such systems are even used to tackle the spread of giant hogweed, allowing exterminators to quickly assess its spread.

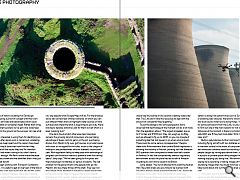

Outlining some of the key benefits of UAV’s David Ashe, drone operator with Top Down View said: “There is much less of a safety concern which gives you the ability to fly close to things such as a chimney stack. You can manoeuvre them in small spaces and you can fly them indoors as well as outdoors without having to put up scaffold or rigging. Surveyors who have learned to fly these things are more valuable to the construction industry than a filmmaker because they understand the workflows that need to happen post production.”

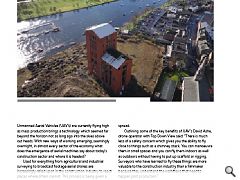

The construction sector is one area to recognise these benefits, although it remains a relatively small part of the industry as a whole, as Matthew Harmsworth, PR and marketing officer for ARPAS, noted: “Only around 10 per cent of commercial RPAS companies specialise in the construction sector but it is likely this will grow dramatically as the media market levels out.” Craig Jump, pilot and director at Sky View Video, has been able to carve out a niche in this area however, saying: “Most of what we do is construction related, we’re doing less and less creative work. The money and the value in using UAV’s is very much on the industrial side. We’ve been using aerial drones to undertake statutory surveys of historic buildings for Edinburgh City Council, including a proof of concept with their own surveyors to look at finials and balustrades which could crumble off and land on someone’s head. Rather than bring in scaffolds and cherry pickers we’ve got a live video feed from the aircraft to the ground so the surveyor can see what we see.

“They’re also interested in using them for identifying an issue before and after repair work is carried out, validating that the money has been spent and the repairs have been done properly. If they’d done that from the start they wouldn’t have had all the issues they had! At Hamilton Mausoleum they had water coming in but didn’t have a cherry picker big enough. We flew a drone inside because they thought it was unsafe and we identified that it was just a piece of lead that fell off.

“We’ve also been working with Transport Scotland to assess landslides. It is useful to get an overview of the task in hand for getting the road open again but also for the public to understand the scale of the issue. We’re also creating photogrammetry maps of these landscapes to understand movement on the hill. You can get down to 1 pixel per 2.5 cm, way beyond what Google Maps will do. For the landslips we’ve also carried near infrared cameras on which you can put different filters that can highlight water courses or hard surfaces and where the lands is beginning to give way. We’re looking to develop airborne Lidar for them as well which is a laser mapping tool.”

One dark cloud amidst otherwise clear blue skies remains the growing band of consumers who are taking advantage of lower costs to get in on the act, purchasing drones from Maplin to fly over golf courses or private houses with scant or no regard for the rules, much to the chagrin of hobbyists and professionals who are licensed, insured and safe. With legislation failing to keep pace with technological progress can the sector realise its potential over the coming years? Jump says: “We’ve been going for five years and there have been no fatalities or serious incidents. The real problem for the government is the people who go into Maplin’s and buy these things off the shelf. They see it on the Gadget Show and think it would be a great idea to take some aerial selfies, they’re the guys flying over football stadiums and city centres. Clients will see those videos and think that looks really nice but as a commercial operator I would lose my license in two seconds creating videos like that. The CAA don’t have the resources to deal with the amount of complaints they’re getting.”

To put the dangers into some perspective Ashe observed that technology at the moment can do a lot more than the legislation allows: “The largest propellers are up to 17 inches and 17,000rpm, they can weigh up to 20kg and are allowed to fly up to 400ft, so you can imagine if something like that lost power in an urban environment. There could be some serious consequences.” Despite these risks Ashe maintains that current British legislation is allowing the industry to flourish, pointing out that there are 862 operators here compared to fewer than half a dozen in America. In fact the comparatively onerous regulatory environment across the pond has led to talk of Amazon migrating its own drone research to Britain.

Jump added: “You’re not allowed to fly anything heavier than 7kg urban areas plus you have to be licensed with insurance and you need approval from the CAA. Approvals allow you to fly within 50m of anyone not under your control, however there are various ways of managing that such as letter dropping adjacent properties. The other option is doing it at certain times such as Sunday morning or enacting road closures. We tend to involve the police and local council when we’re doing things. You can apply for extra permissions from the CAA, so you can get it down to 10m but one of the main reasons for not reducing those distances at the moment is there is no historical data on how safe UAVs are. If they had more data I think they’d relax the rules a bit.”

Built-in redundancies further minimise these risks; including flying aircraft with two batteries and four rotors to maintain control in the event of component failure. Jump also dismisses concerns raised surrounding the privacy of people caught by roving eyes above them, saying: “If you’re in a public or private space taking images then there is nothing stopping you doing that. We normally put a sign up saying we’re recording or taking images of the building. If we are taking images then we would minimise what images we take round about and cut them to the area we’re concerned with.

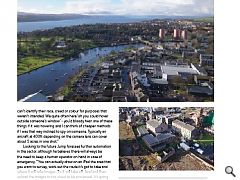

“It’s blown out of proportion to be honest because once you’re up at a few hundred feet you will see people out and about on the ground but you won’t see a lot of detail, so you can’t identify their race, creed or colour for purposes that weren’t intended. We quite often here ‘oh you could hover outside someone’s window’ - you’d bloody hear one of these things if it was hovering and I can think of cheaper methods if I was that way inclined to spy on someone. Typically an aircraft at 400ft depending on the camera lens can cover about 5 acres in one shot.”

Looking to the future Jump foresees further automation in the sector, although he believes there will always be the need to keep a human operator on hand in case of emergency. “You can actually draw on an iPad the area that you want to survey, work out the route it’s got to take and where it will take images. So it will take off, land and then upload the images to the cloud to be processed. It’s going to be less about being able to fly the things and more about professional services but you still need to be able to take over manual control if something goes wrong.”

As cost, technical and legislative constraints recede the sight of drones in our skies look set to become an increasingly common; whether they be analysing heat loss from entire city neighbourhoods or tracking illegal extensions but they are likely to remain limited to simple data gathering tasks. By contrast highfalutin plans for more sophisticated hardware that can actually manipulating the environment around them look set to remain grounded for the foreseeable future.

|

|

Read next: Scotland Build 2015

Read previous: Architectural Highlights of Birmingham City Library

Back to October 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.