Kirkcaldy: Flour Power

15 Apr 2015

Hutchison's Flour Mill, an unusual piece of 21st century process architecture, is a rare example of new dockside industrial construction and the first mill to be built in Scotland for 30 years. Mark Chalmers takes a look.

As a building type, granaries lie at the root of Modern architecture. Ever since Reyner Banham published A Concrete Atlantis, his study of North American grain elevators and their influence on the European avant-garde, we’ve acknowledged the architectural qualities of the granary and the flour mill.The grain elevators in Buffalo, New York are the precursors of Modernism, and most mills and silos built through the 20th century were concrete-framed, sometimes unadorned and sometimes clad in brickwork. Best known in Scotland were the Meadowside Granaries, which stood where Glasgow Harbour is now: they consisted of concrete grain bins hidden behind stark planes of brickwork.

However, the precursors of those giants lie in the water wheel, the quern stone and small-scale milling businesses which grew up beside many Scottish ports. Hutchison’s was established in 1830 when Robert Hutchison began trading in grain, flax, butter and flour from the harbourside in Kirkcaldy. Over time he became more and more involved in the wheat business, and by 1856 his company owned the land at East Bridge on which today’s flour mill stands.

By the middle of the 20th century, “Hutchies” were flour and provender millers, although the majority of their business was in malting barley for brewers and distillers. They had four maltings in Kirkcaldy: East Holms, West Holms and Ravenscraig all packed together to the north of the East Burn, (known locally as the smelly burn, thanks to the effluents which once poured into it) and the Harbourhead Maltings on the southern side.

By the 1980’s the barley-malting side of the firm had declined, and Hutchison’s’ focus shifted towards flour again. The malthouses at Harbourhead were demolished, to reveal the concrete grain silos which fed the East Bridge Flour Mills on the opposite side of the road.

The original East Bridge Mills date back around 200 years. Behind a handsome Palladian office block lies a clutter of old buildings – some stone-built, some in common brick, with an old horse gin buried at their heart. They were chopped and changed over the decades as milling technology evolved, and flour haulage developed from sacks moved by horse and cart, to bulk tankers drawn by articulated lorries.

Due to the low value but bulky nature of the end product, flour operates in what’s known as a regional market. While the mill doesn’t have to be located close to the source of the wheat, it makes sense to be close to its customers – hence a good proportion of the flour milled at Kirkcaldy is used by Scottish bakeries.

Our climate is ideal for growing softer, lower-protein “weak” wheat, perfect for baking cakes and biscuits. However, much of the bread we eat is made from North American, Russian or German flour as those countries grow stronger, high-protein wheat. Much of the latter was brought in to Hutchison’s by sea, until Kirkcaldy’s port closed to cargo traffic.

A few years ago, when the brick-built flats went up on the northern quayside of the inner harbour, the docks consisted of dead wharfside with some nautical-themed street furniture and the occasional pleasure craft. As with stretches of waterfront in Greenock, Dundee and Leith it seemed that housing was more lucrative than seaborne cargo, but that shift resulted in a hollowed-out town.

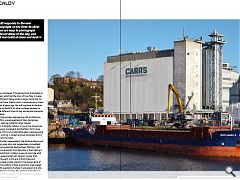

Kirkcaldy lost its authenticity when commercial shipping ceased – but it was redeemed after Hutchison’s Mill was taken over by Carr’s Milling Industries in 2004. With a significant investment from Carr’s and Forth Ports, the harbour reopened to wheat imports after a break of 20 years, allowing grain to be brought directly into the mill by sea, whether from the south of England or across the North Sea.

The first shipload was landed in August 2011, when a vessel from the German port of Rostock brought in 2000 tonnes of wheat: now grain ships deliver every few days, removing 250,000 lorry miles from Scotland’s roads each year. That was the first step in a strategic plan to re-develop Hutchison’s mill.

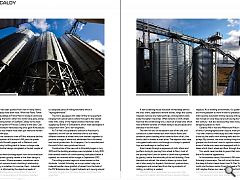

In 2010, when Carr’s decided to reopen the port, they also constructed new concrete grain silos on the portside, and purchased additional land for future expansion. A couple of years later, Carr’s engaged the Hull architects Gelder & Kitchen to develop a brand new flour mill in Kirkcaldy. The practice has a long heritage of designing mills, and amongst other commissions, they worked for one of Carr’s competitors to build Clarence Mill in their hometown of Hull.

It’s rare for a new flour mill to be constructed – Carr’s Hutchison’s Mill in Kirkcaldy is the first in Scotland for 30 years – and in a 21st Century society which underplays industry and often submerges its functions in dumb boxes, Carr’s decision to develop a new mill on a prominent dockside site in Kirkcaldy is unusual and noteworthy.

Industry has been pushed from view in many towns: and in Kirkcaldy more than most. While the Plains Tower and Stoves buildings at Forbo-Nairn’s linoleum works are still standing, the town’s other lino works have gone, along with the winding towers of Seafield Colliery to the west and the great sprawl of Frances Colliery to the east. Coal mining and linoleum manufacturing once gave Kirkcaldy its identity; their loss meant more than just men and women looking for new jobs.

Against the consensus view of Fife’s industrial decline, the redevelopment of Hutchison’s Mill joins the power station at Tullis Russell’s paper mill in Markinch, and Diageo’s whisky bottling plant at Leven, as large scale pieces of industrial design completed in the last couple of years.

What sets these buildings apart from the architecture which magazines typically review is that their design is driven by process. Where reviewers sometimes settle for the correct opinion about a building’s relationship to its setting, or whether it is comme il faut – industrial architecture is informed by the objective needs of machinery. Nothing more, nothing less. In the case of Hutchison’s, close analysis of the process resulted is a bespoke piece of milling hardware which is “reprogrammable”.

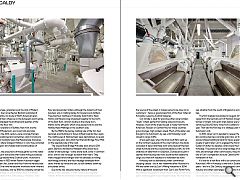

The mill is equipped with state-of-the-art equipment ranging from optical grain sorters through to the newest roller mills, many of the highly-evolved machines were supplied by Buhler of Switzerland, which were developed in conjunction with Carrs’ own engineers.

As Tim Hall, the operations director at Hutchison’s explained, the mill can be switched over to suit many different varieties of wheat which are blended together to produce a range of white and wholemeal flours for bread and biscuit production. As it happens, Carr’s manufactured the world’s first mass-produced biscuit.

Construction of the new mill in Kirkcaldy began in July 2012 and the building envelope was completed in July 2013, then several months of commissioning took place before it opened, on time and within budget in September 2013.

The milling process begins at wheat intakes on the dockside. I visited Kirkcaldy on a crisp winter’s day, as a material handler drew grabfuls of wheat from the hold of the MV Britannica Hav. A giant hydraulic arm swung around to empty its grab into the intake hopper which feeds the grain silos.

A new screening house was built immediately behind the silos: there, separators remove stones, twigs and cockle, magnets remove any metal particles, and aspirators blow away the lighter impurities. What remains is 100% wheat. Next are the conditioning bins, a new set of steel silos which hold different varieties of wheat ready to be processed and blended in the mill itself.

The new mill sits on the eastern side of the site, and consists of a steel-framed box with Holorib floors and sandwich panel cladding which take the form of tall, slim blocks clad in shades of matt silver. The adjacent silos have corrugated walls which rise through six storeys to peaked tops and walkways at rooftop level.

Grain travels through a sequence of mills, sifters and purifiers during its journey from wheat to flour: most of the journey from Level six down to Level one is powered by gravity, hence the verticality of the mill building. Once blended and refined, the wheat is blown up into a final set of silos ready for dispatch. Hutchison’s produce bran, wheatgerm and animal feed from the by-products of milling, so nothing is wasted.

Chatting to Carr’s employees, you soon learn that the new mill is better than the old one in several different respects. As a working environment, it’s quieter, brighter and more pleasant to work in than its predecessors. Older mills become redundant mainly because milling technology has moved on since they were built during the first half of last century – but also because they were noisy, dusty and dangerous places to work.

Clarence Mill in Hull and Millennium Mills in London, both of which I photographed after closure, were photogenic – but their interiors were dusty and their machinery was driven by line shafts with whirling belts and thrumming pulleys. By contrast, the most striking thing from my brief glimpse into Hutchison’s was its spotless interior, finished in tones of white and cream and equipped with hundreds of tubes which direct wheat and flour through the mill. You would never be able to guess that complexity from the mill’s external appearance.

In the broadest sense, Hutchison’s Mill contributes to Kirkcaldy’s townscape. The mill sits at the foot of Pathhead, the steep hill which leads down from St Clair Street and the north into the town centre. From the head of The Path, the mill’s skyline frames our view out over the Forth, skimming the rooftops where Kirkcaldy’s linoleum industry grew up.

The massing of silos, bins, screen house and mill is architecturally considered. The elements are articulated as a series of layers which tell the story of how flour is made, and avoid Hutchison’s being simply a large, dumb box. As with Cockenzie Power Station which I wrote about in Urban Realm a couple of years ago, the mill responds to the ever-changing light on the firth: its silver surfaces are easy to photograph at different times of day, and almost mercurial at dawn and dusk.

By combining process engineering with architecture, Hutchison’s Mill is a good example of inter-disciplinary design, and a positive model for other coastal developments. Kirkcaldy harbour is now a true mixed-use area, with housing, a boatyard and the flour mill in close proximity. The mill is truly sustainable again, because using sea transport to bring in wheat removes hundreds of lorry movements from the roads.

In terms of urban regeneration, the scheme retains and reuses existing grain silos, and regenerates a brownfield site which once housed the Harbourhead Maltings – but perhaps the crucial lesson from Kirkcaldy is that making a building like Hutchison’s visible is a way to reconcile what we buy in the supermarket with where it comes from.

As a final thought, in this era of food miles and traceability we take a close interest in the provenance of what we eat. The politics of food production preoccupies journalists with questions of where it was grown and who made it. Hutchison’s employs 70 people to make flour in their new mill, and journalism – even the architectural sort – is always, at heart, about people.

|

|

Read next: Sauchiehall Street

Read previous: Royal High School

Back to April 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.