Fore Street

19 Jul 2012

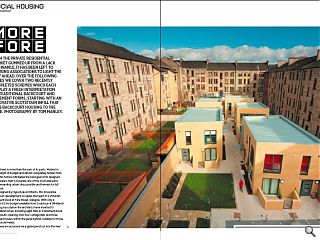

With the private residential market gummed up from a lack of finance, it has been left to housing associations to light the way ahead. Displaying a fresh interpretation of traditional back court and tenemental forms this Scotstoun infill puts backcourt housing to the fore.

Designed by Hypostyle Architects, this innovative backcourt development occupies the heart of a Victorian tenement block at Fore Street, Glasgow. With only a modest £1.5m budget available from Scotstoun & Whiteinch Housing Association the architects have inserted 15 affordable homes; including eight flats in a tenement block to the south, opening onto four cottage flats and three detached houses within the pend behind, suitable for those with special needs.

These are accessed via a gated pend cut into the new build flatted block and replace a former bakery and car repair workshop – both of which had long since been abandoned and fallen into a state of disrepair, to the extent that they had become a health hazard. Addressing issues of privacy, access and the provision of amenity space, the development is built around an intimate pedestrian lane with properties staggered at either side, with all principal rooms given a southerly aspect. A staggered layout affords each property an unobstructed vantage over intermediate spaces which have been landscaped to form garden courtyards.

Giving Urban Realm a guided tour around the development was project architect Grant Donnan, who recalled the dire condition of the site as he found it: a warren of dilapidated buildings which served as a breeding ground for rats and acted as a fire hazard, Donnan said: “One of the things that was key to the development was the state of the site. If this had been gardens it wouldn’t have happened but because of the condition of the site beforehand both planning and the residents of the surrounding tenements were happy for the site to be developed. There wasn’t any other way to redevelop this site unless you were going to turn it into a park - but who is going to pay for that?”

Even so this is a scheme which could only have been progressed by a housing association, as Dave Sherry, development officer at Scotstoun & Whiteinch, explained: “In the inner city the only sites are difficult sites. A private developer would have never got planning permission because of the requirements for parking - for social rented housing you don’t need 100% car parking. If you’d put 100% parking in here it would have cost a fortune and with the density of the site planners were never going to allow a 24-storey block.

“We’ve got very few projects, it’s difficult and expensive to acquire sites, made worse by the recession. We’re looking at a number of other locations but we don’t have funding for anything because of the cuts. We won’t have any other developments for at least two years, I think, because two things have happened. They’ve cut the subsidies to nothing and they’ve cut the amount of grants. So there is competition for very little cash among lots of different housing associations.”

Despite these disadvantages the site does actually boast several strengths, chief amongst them proximity to the west end and excellent transport links including, possibly, a Fastlink bus route which will run along a disused railway line to the site’s immediate south.

The need to maximise daylight was one of the reasons Hypostyle plumped for honey brick as it’s quite bright, deliberately eschewing white render because of maintenance concerns.

Outlining his approach Donnan said: “Keep it simple, don’t mess things up with five different materials. It can’t be costly to maintain. Originally we were worried because the block was south facing that we wouldn’t get the light but we’re not even into summer yet and you can see the sunlight. Even in the winter it’s still fairly bright although you don’t get the bright sunlight.”

At night a series of wall lights, bollards and uplights come into play in a bid to impart a sense of safety and security to communal areas, although Donnan admits that the use of glass blocks to draw light was a compromise, saying: “Originally we wanted Reglit but you can’t get the sixty minute fire resistance, only half an hour, so we had to go with glass blocks.”

On the question of whether the development could act as a template for other courtyards throughout the city Sherry remained sceptical however, pointing out that the dimensions of most backcourt spaces often conspire against them, saying: “There are examples of this in other parts of the city but it’s rare. Traditionally a lot of backcourts were closer together, but where there were workshops and wash houses, you can do it - as long as the tenements are still standing. The problem is for a housing association every project is a one-off because the local and site conditions available are all different. You would never do something identical to this but the idea is something we would use again if we found another site.”

Unfortunately sedum roofs weren’t deemed to be realistic for the build, despite the degree of overlooking, as the timber roof trusses wouldn’t have supported it. Donnan also pointed out that they can look “pretty grubby” with much of the budget directed below street level: “The ground conditions weren’t the best, being so close to the river, so we spent a bit piling throughout. We originally thought we’d just have to pile the flatted block because of the size of it and cantilever the ground floor slab over the ground beam and then build a new boundary wall off it so we could right up close to it.”

Fore Street’s greatest success is in lighting the way to a sensible reuse of tucked away and forgotten spaces. As Scotstoun & Whiteinch have astutely observed it is these secondary places sourced through local knowledge, economic only to specialist users and possible only in the social sector, which hold the key to the sustainable expansion of inner city neighbourhoods. It is disheartening therefore that just as the template for such housing has been built he funding environment that made it possible has evaporated. At least when the economy does pick up projects such as this can show the way ahead.

Photography by Tom Manley.

|

|

Read next: Reflections on the Serpentine Pavilion

Read previous: Doomster Hill

Back to July 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.