Vaudeville Performance

14 Jan 2010

Scotland's national dance company, Scottish Ballet, has ample cause to celebrate its 40th anniversary having recently moved into purpose built accommodation at the Tramway on Pollokshaws Road in Glasgow's south side...

This despite a challenging locale that many have decried as something of a graveyard for modern developments with a depressing slew of low budget horrors for neighbours. The most infamous of which being The Plaza which emerged as the unanimous winner of this years carbuncle award for "worst new building".

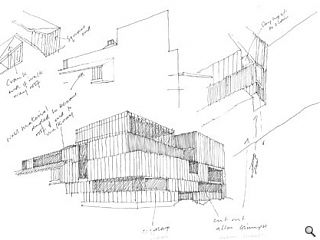

It is within this unpromising context however that Fraser has attempted to insert something of design merit whilst also accommodating the client's brief which called for provision of three key spaces: a scenery and technical workshop on the ground floor to allow delivery by lorry, an administrative space, music, wardrobe and storage area and most importantly rehearsal studios with light streaming in from above. It is the latter spaces which form the heart of what Scottish Ballet does and provide by far the most dramatic spaces with one room claimed to be Europe's largest rehearsal space, easily eclipsing Covent Garden's meagre 18x18m dimensions with a hefty 20x20m rooftop eyrie.

Indeed so voluminous is the space that it regulates its own microclimate, venting hot air through a series of nine skylights (each blinded to allow sunlight control) without recourse to mechanical ventilation. So successful is this passive system at wafting stale air from perspiring bodies that it is calculated that the working environment would only become uncomfortably fetid on days exceeding 30 degrees Celsius, climatic conditions of fortuitous scarcity. In addition the solid mass of the building's concrete floors prevents over heating in summer and cooling in winter whilst high level windows eliminate cold drafts circulating amongst performers; more than a discomfort these can cause muscular contraction and expose dancers to risk of injury.

In addition to temperature regulation these skylights also serve to infuse ample natural light into interior spaces, which itself helps reduce running costs. Pre-armed with statistical evidence, project architect Clive Albert purports that some 60% more daylight is provided through a skylight than a corresponding window with the result that despite being 50% bigger than the old office, running costs are only 1% more, stating: "Gone are the days when you hermetically sealed a building and control temperature mechanically. We can't go on like that or we'll destroy the planet".

A seemingly fair construction budget disguises the portion of money spent on the existing Tramway building, which had to be kept open during the works and was remodelled internally to include a new visual arts studio. Delivered for £1,400sq/m as opposed to a more typical £1,600 for a commercial office block, the scheme was built to the same sq/m cost as Fraser's Dance City from 2001-5, despite subsequent inflation in building and materials cost. This necessarily led to a stripped down building.

Despite the external appearance of a brand new building the Tramway dates back to 1893 and its original role to house horse drawn trams. Long ramps provided access from the buildings south side into stable spaces which lent themselves to office conversion as Albert explained: "We were worried about acoustics in an open plan office so installed perforated plasterboard to deaden sound. Old buildings always house surprises; we had to relay our floors because you couldn't sit at your desk, all the floors were originally built on a slope for stable cleaning!"

One feature of the unloved previous accommodation that management were keen to replicate was a large staircase and landing upon which people tended to congregate. This was reborn as a "social court" to bring people together as Albert describes: "The importance of this space is articulated through extensive Douglas fir cladding to imbue a warmth, character and harmony and acknowledge that this is something different. In a working building walls and doors inevitably become bashed but by using materials like wood which mature with age this building will look better in 20 years time than it does today with minimal maintenance."

This attention to detail is reflected in services provision with power cords dropped from the ceiling to avoid trailing cables, sliding doors (a Fraser staple) to allow users to divide and double up space in accordance with need, stairwells wide enough for a dancer to ascend in costume and even a window sunk between the main entrance passageway and fabrication hall, allowing passers-by to glimpse the previously hidden world of stage construction.

Externally the main parapet lines of an adjoining church dictated height, necessitating a flat roof to maximise internal spaces. Clad in anodised aluminium with ground level concrete to handle the knockabout nature of a street frontage, the finish is textured to naturally discourage vandalism. Albert stresses: "A lot of people doubted the nature of the cladding but look at the grim render and badly stained bricks of neighbouring developments. These act as magnets for airborne particulates and simply don't work in urban areas. This sheeting is vertically profiled to self clean in the rain and we deliberately used dark gold because of all the range of colours available through the chemical process the deepest gold fades least when exposed to UV."

Speaking of the lack of ostentation in the design Albert explained: "It is a factory and not by and large a public building. It is used to create, experiment, perform and rehearse and is thus very different to what you would experience in the theatre."

Lady luck offered a helping hand to the designers too, placing a fortuitous kink on the Pollokshaws Road site which grants an open view to Glasgow through floor to ceiling glazing and a patch of greenery opposite imparts a sense of nature in the urban location. Further cognisance of site is demonstrated by the insertion of a projecting social space looking up an adjacent railway line.

An uncompromising pursuit of minimalism was discounted by Albert, however, who considered the style in its extreme as inappropriate for a working building as previous precedent with the removal of skirting boards had led to residue build up on the walls from cleaning processes, and white doors, whilst looking pretty initially, quickly become scruffy when users neglect to use the push plates and spoil the paintwork.

Clearly then the team at Malcolm Fraser has performed a commendable job in accommodating the needs of Scottish Ballet and its pedigree in the field does shine through in the many small details to be found within. It is perhaps the bigger picture though that is less immediately pleasurable with a somewhat utilitarian finish requiring more than a drive-by glance to fully appreciate. It is stated that the building has been designed to mature with age and as neighbouring schemes rapidly lose their new build sheen that disparity in quality can only become more pronounced.

|

|

Read next: Pedestrians First

Read previous: Best Laid Plans

Back to January 2010

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.