Tornagrain

25 Jun 2009

Willie Miller investigates how New Urbanism is now beginning to shape our communities and asks how one proposed new town in the North East might provide a better model for sustainable communities.

Proposals for a new settlement at Tornagrain are currently the subject of an outline planning application to Highland Council following a two year gestation period of analysis, charettes and plan making. The proposal, submitted by Moray Estates and designed by a team led by Duany Plater-Zyberk (DPZ) is just one of a number of broadly similar proposals throughout Scotland which follow an approach that can be loosely described as traditional urbanism. Of these developments, Tornagrain overtly demonstrates the principles and practice of New Urbanism while the Prince's Foundation for the Built Environment proposals at Ellon designed by Urban Design Associates (UDA) and Cumnock display the same concern to emulate successful traditional towns but also emphasise traditional building as an integral component of the developments.Andres Duany of DPZ was recently described by Jim Mackinnon, Chief Planner at the Scottish Government as Ôthe Tiger Woods of town planning' and while he is lauded by the Scottish Government he, and the traditional urbanism project in general, are held in particularly low regard by many Scottish architects. Although Duany's background is in modernism and Miami based firm Arquitectonica, he forsook this to concentrate on urbanism, designing Seaside and a series of other new settlements before going on to form the Congress for the New Urbanism in 1993 based on the structure of CIAM.The Scottish Government has clearly taken urbanism issues seriously with a slew of publications aimed at increasing the standard of new development, a curiosity about how high standards are attained in other countries and initiatives such as Design Awareness Training for Council officers and elected members through the Improvement Service and the recent Scottish Sustainable Communities Initiative. The alignment with traditional urbanism and sustainability is clearly aimed at improving the quality of development in new communities and in extensions to existing settlements although some of the ideas spill over into the consideration of new interventions in established urban areas.

The reasons for this adoption of traditional urbanism are fairly obvious. Firstly, volume builder residential developments are not improving and there is little sign that they will. Planners are usually unable to make significant positive changes to these developments despite a plethora of conditions, design briefs and codes. Many are wrong from the outset. Secondly, a proportion of sites allocated in Local Plans for housing are often ill-chosen in relation to their potential impact on the town, transport, intrusion in the landscape and on habitats and a standard product residential development will usually exacerbate these difficulties. Traditional urbanism is by its nature sensitive to context and place and has principles and methods of practice that create developments embodying much of what is regarded today as best practice in planning and urban design so even on a poor site, it will create a more sensitive response. Thirdly, experience from around the world says that traditional urbanism sells. The VINEX urban extensions in Netherlands such as Brandevoort, Leidsche Rijn and Haverlij designed by Rob Krier, Mulleners + Mulleners, Schippers Architects and others are all incredibly popular despite the country's reputation as being Ôthe most appreciative of modern architecture in the world'. It is the same story in the United States where New Urbanism is a major factor in selling new homes.

Looking at Tornagrain in more detail, it is remarkable for a number of reasons. The basic statistics are for a town of 10,000 people set out as three distinct neighbourhoods each with local centres, a town centre, central park area, green belts between neighbourhoods and a realignment of the A96. The basic plan form was created over an intensive ten day programme of public meetings and design sessions in a completely open process and incorporates all of the New Urbanism principles. These sessions dealt with regional context, business, transport issues, infrastructure, ecology, landscape, housing, social and economic issues. The plan has proved to be very resilient and has only changed in minor ways between the charette process and the submission of the planning application to reflect new issues raised by the community such as the provision of allotments and other factors emerging during the preparation of the Environmental Impact Assessment. The plan includes a supermarket, primary and secondary schools, police, fire and ambulance services, hotel, community leisure and sports facilities, a park, health centre and railway station set in a mixed use framework. The future development of the town is controlled using a design code and transect which regulates almost all aspects of development. One of the keys to creating this plan is that Moray Estates has been in the area for hundreds of years and intend remaining there and so can afford to take a long term view of the development. The current estimate is that it might take 20 years to complete so this is no short term business like most of the house building industry.

The parallels with Poundbury will not have gone unnoticed. On the face of it, Duany and the local communities around Tornagrain have succeeded in producing an well structured proposal for a mixed use settlement encompassing principles of walkability, variety of dwelling types, local shopping, schools and traffic attenuation. These are also attributes of Poundbury which has been incredibly successful in establishing a mixed use urban extension with successful businesses, employment and community facilities within a pedestrian orientated environment.

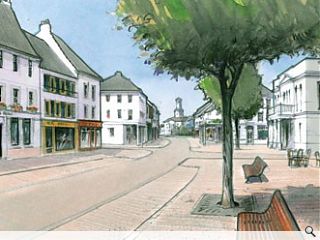

Of course the issue of most concern to planners and architects alike may well be the architecture of the settlement and the chocolate box images which accompany the masterplan document. In the case of Tornagrain, like Ellon, Cumnock and Poundbury, the landowner has set out to acquire a traditional settlement with buildings of a traditional appearance Ð that is what they want. Moray Estates maintain that over the twenty year development period for the town, it is inevitable that there will be variations in style but for now they are content to let the code produce an appropriate range of traditional buildings for the town.

What distinguishes this recent urbanism in Scotland is the emphasis on the principles of town making and urban structure, the inclusiveness of the plan making process involving local communities, the elevation of sustainability to the status of core issue and the de-emphasis of architecture as end product. Another factor common to all these developments is that they are all being promoted by major landowners who are in the developments for the long term.

These are all critical components of an urbanism approach. Getting the structure of the town right is the main objective and if that is done, planners shouldn't need to interfere in design and the architecture debate can continue unimpeded in its bubble. It's not about what things look like but how they work.

Architects may rail against New Urbanism for its association with the past and its chocolate box aesthetics, its perceived lack of radicalism, betrayal of modernism and a host of other reasons but for now, traditional urbanism seems to be the only game in town, in Scotland at least, and the work of DPZ, UDA and the Prince's Foundation together with a few other practices are setting the pace in the design of new settlements and urban extensions. Architects may consider urbanism to be an integral part of architecture - and it probably was once - but from the late 70s and early 80s in the UK, urbanism started to branch off from architecture and has become an established discipline in its own right. Of course this doesn't mean that architects and planners can't or shouldn't practice urbanism Ð they obviously do Ð but what it does mean is that a different agenda is being established in which the shape-making and form-giving that once passed for urban design and the underwhelming architectural masterplans for the development industry wrapped up in elemental philosophy about space, sunlight and openness just don't cut it anymore.

Love them or hate them, traditional urbanism plans like Tornagrain represent a quantum leap forward for the practice of urbanism in the UK but the sound principles of urban structure expressed in these plans need to be evolved by all those involved in building towns and cities. There is a danger that this strong foundation will lose direction through early institutional acceptance and become ossified, like planning and urban design, in statutory box ticking and standard solutions. Traditional urbanism should not be the only urbanism practiced in Scotland Ð it won't always be the right answer but it is a good basis on which to build. Scottish urbanism should be a broad movement that accepts that the production of the built environment should not just be the domain of the increasingly irrelevant historic professions but should embrace communities in a wider social, economic and political agenda.

Read next: Building momentum

Read previous: Crab Shakk

Back to June 2009

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.