Architectural Competitions: A Mugs Game

24 Apr 2017

Peter Wilson, architect and director of Timber Design Initiatives, focuses on two recent projects; the Ross Bandstand and a new concert hall for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra to illustrate where we are going wrong.

Many architects nowadays avoid entering design competitions, the reasons being many and varied. Principal amongst these, though, are that they are expensive in time and other resources and, with a profession predominantly comprised of small practices, these are resources that can be ill-afforded. More worrying is the widespread perception that there is little chance of securing a commission in this way, so why bother? Yet in much of Europe, competitions are a way of life for architects, with clear structures that define whether, in the invitation to practices, the contest is local, national or international and whether it simply seeks ideas only or is a project that will be realised. In the latter case, if it is for a publicly-owned site and for a public building, substantial consultation is very often required prior to the brief being written in order that there is broad consensus on the type and scale of project required. The politics too are resolved beforehand to ensure there is no dispute or interference after the competition has been judged and the winner announced; and the finance has been assembled in advance to provide confidence that the commission will proceed. To all intents and purposes, if the competition project falls within the realisation category, it will almost certainly be built.This also applies to local contests for which a limited number of practices have been invited and for whom entry to such competitions can be a primary source of work, the presumption being that one or two wins a year will provide the bread and butter income needed to sustain the office for a longer period. Larger projects are often two stage, with shortlisted teams given sufficient money to produce entries of the quality required for comparative purposes. Some practices have in fact established themselves on this basis (Jean Nouvel comes to mind): even in instances when they fail to win, the payment for being shortlisted has been sufficient to sustain the office. Competition documents, rules and judging processes too, are generally consistent, the systems having long been in place to give entrants confidence that, with every submission made on the same like-for-like basis (i.e. the form of drawings, models and other materials are strictly defined) their work will be given even-handed consideration.

Of course, this is a very generalised summary of how competitions work elsewhere and there are always anomalies to be found: the point is that it is possible to have a consistent competition system in which entrants can have confidence, as opposed to feeling the dice are loaded against them. So why is it that, almost uniquely, the UK - and Scotland in particular - has failed to establish processes that encourage politicians, clients, public and architects themselves to favour the use of design competitions to find the best possible solution? We don’t need to spend too much time identifying the reasons: unlike our continental colleagues, we too often try to solve political issues through competition, the result being that the problems fail to go away and the projects fail to proceed into construction; we also accept that funding might not be in be in place before a winner is selected, a method that presumes architects’ entries are merely a sub-set of a marketing campaign. Planning issues unresolved in advance, mis-use of OJEU processes, public opposition: the list goes on.

This brings us to the situation today, in which architects have come to accept competition structures that not only are inconsistent in process and open to criticism about the experience of the sponsors and the objectivity of the judges, but which actively work against the interests of the bulk of the profession in the terms used to restrict entries and in the opacity of the selection process. Unable themselves to meet the impossibly high competition conditions that are often set (whether these relate to size of office, specific experience, insurance cover), many practices seek to align themselves with others - often larger and, increasingly frequently, those from elsewhere with international reputations, the latter ironically achieved through success in the more consistent competition world outlined above. The results are drearily predictable: an international name will be announced, with a team of local bag carriers in tow to deliver the project. The international name is used to sell the idea to politicians and the public which, once achieved, can be the end of their intensive input, flown in again only when a p.r. opportunity is planned. Yes, there are arguments for and against this state of affairs, but the net result is that the idea of architectural competitions here has not only been seriously devalued, but arguably is now being used to circumvent established democratic processes.

Two privately-run competitions for major schemes in Edinburgh that, to all intents and purposes, would be classified elsewhere as public projects, merit examination because they exemplify much that is wrong with the way we do things here. In principle, these projects - one for a new concert hall for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and the other to replace the Ross Bandstand in Princes St Gardens - are entirely laudable and much needed, but the circumstances surrounding them deserve rather more scrutiny than they have had so far.

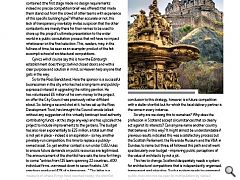

The concert hall site sits behind what was once the proud headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland that faces on to St Andrews Square. Roughly triangular in shape, this piece of land might otherwise be regarded as a prime piece of real estate in the New Town and thus a highly valuable asset to a financial institution that continues to deconstruct in the aftermath of the expansionist hysteria that overtook, and almost destroyed, it in 2008. The bank only survives to this day courtesy of the UK taxpayer, so one would expect its assets to be under forensic scrutiny to ensure it it is able to repay the vast public investment made to secure its existence. Yet some kind of deal seems to have been done to allow ownership of this land to shift to another body, the terms of which have not been made public. The client body too, is a new trust, with no track record of building anything although, to be fair, several of its members have some experience in this area. There appears to be some money (a glossy ‘competition’ does not come cheap, especially when organised by a London-based p.r.company), but certainly not enough to meet the £60 million project budget. So where will the rest come from? The brief states that the contest will be run under OJEU rules, surely not a requirement for a private project, but an essential one if the sponsors wish to access public funds - such as the National Lottery - and ultimately to demand (as they surely will) Scottish Government financial support.

The competition documents are intriguing and, from the level of detail provided, indicate that some substantial discussion has taken place with the city planning department, but it is hard to be sure on this because, although a feasibility study has been carried out, it was not made available to initial supplicants wishing to participate in the contest, nor can shortlisted entrants see it without signing a confidentiality agreement. So why the secrecy? Actually, this desire to contain knowledge of the client body’s intentions extends into the shortlisting process itself, with highly specific requirements made regarding experience, forcing many to follow the bag-carrier path, with the predictable lack of success. The assessment criteria, whilst listed, gave no real indication of how each would be scored, a time-honoured indicator that even-handed selection is not a factor in the final decision. And so we get to the shortlist: intriguingly, the architects who produced the secret feasibility study is on it, whilst another is a practice with long-term, well-known links to members of the client group. Neither, however, is an obvious candidate with a track record of building 1000 seat concert halls, so we are left to beg the question as to what their submissions contained (the first stage made no design requirements: indeed no precise competition brief was offered) that made them stand out from the crowd of other teams with experience of this specific building type? Whether accurate or not, this lack of transparency inevitably invites suspicion that the other contestants are merely there for their names to be used to shore up the project’s ultimate presentation to the wider world in a public consultation process that will have no impact whatsoever on the final selection. This, readers, may, in the fullness of time, be seen as an exemplar product of the fait accompli school of architectural competitions.

Cynics will of course say this is how the Edinburgh establishment does things: behind closed doors and with a clear purpose and solution in mind, so Heaven help anyone that gets in the way.

So to the Ross Bandstand. Here the sponsor is a successful businessman in the city who has had a long-term and publicly-expressed interest in upgrading the rotting pavilion. He has volunteered £5 million of his own money to the project, an offer the City Council was previously rather diffident about. So, taking a second shot at it, he has set up the Ross Development Trust, has brought the Council onside (albeit without any suggestion of this virtually bankrupt local authority contributing funds - at this stage anyway) and has upscaled the project to include improvements to the gardens. The budget has also risen exponentially to £25 million, a total sum that is not yet in place - indeed is an aspiration - so hey, another privately-run competition, this time to replace a publicly-owned asset. So, yet another contest is run under OJEU rules to ensure future demands on public resources are legitimised. The announcement of the shortlist here sets the tone for things to come: “entries from 125 team spanning 22 countries…400 individual firms…narrowed down to seven finalists…UK practices produced 42% of submissions…” The latter is a measure of where things have reached today: the shortlist gives every indication that Scottish-based companies now recognise they are unlikely to be selected on their own merits in this type of contest, so are themselves approaching big international names in the hope that being attached to proven winners will significantly improve their chances of ever working on a substantial public project in their own country. Indeed, one such has had the sagacity to align itself with at least two international names, thereby raising its chances of success in the seven-strong shortlist from 14% to almost 30%. The logical conclusion to this strategy, however, is a future competition with a stellar shortlist but for which the local delivery partner is the same in every instance.

So why are we doing this to ourselves? Why does the profession in Scotland accept circumstances that so clearly act against its interests? Can anyone name another country that behaves in this way? It might almost be understandable if previous results indicated this was a satisfactory process but the Scottish Parliament, the Riverside Museum and the V&A in Dundee, to name but three, all followed this path and all went spectacularly over budget - improving public perceptions of the value of architects by not a jot.

This has to change. Scotland desperately needs a system for architectural competitions that is independently organised, transparent and objective. Such a system needs to command public trust and not be open to manipulation by vested interests. It needs to be applied to every public project and structured in such a way that it is in developers best interests to utilise the process. The competition system needs to be part of the next iteration of architecture policy, which itself needs to have statutory status as part of economic and industrial policy. None of these points are rocket science: they work in other jurisdictions. The question is: does a downtrodden profession have the will to exert pressure for change or will it continue to be happy to be part of the Scottish cringe?

Read next: Banana Flats: Dishy Leith

Read previous: Superior Interiors

Back to April 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.