The Power of Place

20 Oct 2015

Following the Power of Places and the Places of Power, an event hosted by the University of Glasgow, research fellow Dr Georgiana Varna and urban planner Seren Sezer challenge assumptions about the state of our public spaces.

Many contemporary cities have been redeveloped by a wide spread capitalist system fuelled by a neoliberal ideology, not only in the Western world but also in Asia and Africa. One of the main consequences of an increase in the privatisation and commodification of urban public space by the states, developers, or other related parties, which tend to view the citizens as consumers, rather than active citizens of the cities. This implies that the production of public spaces is embedded in a certain set of power relations, which are increasingly contested by both researchers and engaged members of the public who feel left without a voice in the shaping of their environment. It follows that a crucial question today is who controls the urban development and design process? In other words: How does power work when space is transformed from one stage to the other? Who decides on the best scheme? And in relation to this, what is the best way to involve ‘the public(s)’?Urban public spaces: from parks and squares to streets and community gardens – are the most contested places of the city. Traditionally, urban public space has been the arena, where different groups can co-exist, where basic rights such as freedom of access and freedom of expression are guaranteed. It is the space owned by all, there to be used and enjoyed. As such, the main power of urban public space is to foster diversity and equality, to allow ‘strangers’ to meet and interact, and as such it is fundamentally a reflection of democratic values.

However, urban public space is the quintessential space where the power of the ‘state’ and generally formal institutions is constantly negotiated and sometimes contested by the power of the people. On one hand, these spaces are produced through the logic of the real estate development process, with the powerful actors, planners, architects, landowners and developers trying to shape them according to their own goals. This is taken to extreme in the United States where the shopping mall has become the common public space for many suburban developments.

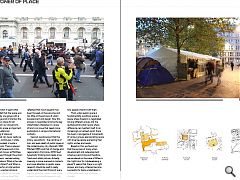

In relation to this, in order for urban public space to remain a truly democratic space, any urban (re)development scheme needs to involve various members of the public from the beginning. As such the power of the people needs to be put on the same level with the power of the decision makers; the most successful urban projects seem to happen when people were asked from the start: What kind of place would they like to live in? Of course, there can never be full consensus, but only when their concerns, wishes and visions were incorporated in the development process, was the result a place that was meaningful for the inhabitants, that was used and as such economically successful.

At the same time, urban public space is the part of the city that can be most easily appropriated by diverse groups, against the main institutional norms and regulations. This can happen both in tacit, incremental ways through ephemeral activators such as street vendors, the mantero on the streets of Madrid or through the reclaiming of a part of the city, being given a new temporary use, such as the “New Generation Squats” in Rome. Clemens Nocker from Sapienza University in Rome, showed how these represent appropriations of many historic sites of the city, transformed illegally in cultural centres by various groups. The program of each of these spaces is based on an open hybrid space with various uses (lectures, concerts, working spaces, sports facilities) and it’s within the crossing of these different activities and publics that much of Rome’s local culture is produced. Generally, these spaces can be seen as part of more ambitious strategies of urban regeneration or transformation of neighborhoods through community building, as Juan Arana, an architect from Spain described.

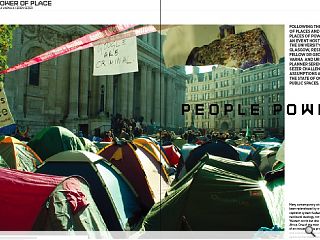

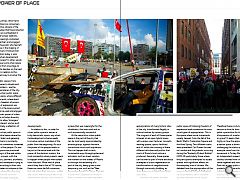

However, the power of urban public space of fostering freedom of expression leads sometimes to more vocal types of appropriation. This is the space where social movements usually happen, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to Tiananmen Square and the Arab Spring. Two different cases were presented. Carl Fraser focused on London and the protests occurring during the “Austerity Protest Bubble” (2010-14) particularly those where the participants attempted to access spaces with significant effects on the everyday lives of citizens. We debated how the appropriation of the space in front of St Paul’s Cathedral by the protesters, left it unusable by other members of the ‘public’. Therefore there is a fundamental tension as how far does the power of public space allow for the freedom of expression of a certain individual or group? It seems that it depends highly on how the appropriation of a certain space is done by the ones challenging the status quo. A different example came from the Gezi Park movement in Turkey; Basak Tanulku, an independent researcher from Istanbul showed how various groups came together and transformed Gezi Park into a lively public space through protests, collective action and solidarity. Both spaces in London and Istanbul regained their importance and meaning as a medium for politics, however in London it seems that many people felt that the space was appropriated by one group with a certain message and in Istanbul the space became a ‘place for all’.

Overall, from our discussions, three key points arose as important.

First, the Lefebvrian understanding of space as ‘something’ that can never really be designed, in a continuous in state of flow was prevalent in quite a few presentations. There is always a multiplicity of spaces and in this multiplicity that moves, as Matthew Carmona showed through the urban-design continuum, we kept asking two main questions: What is the role of designer/architect? and When is it the right time for an intervention to be made in a certain physical space and who should be the ones deciding what is to be done? We reflected that much research has been focused on the outcome and too little on the process of urban development and design. How this process is negotiated among the key stakeholders interested in a piece of land is an issue that needs more exploration in various international contexts.

Second, we discussed that the binary oppositions - the narrative of loss, and even death of public space in the contemporary city (Sennett, 1992; Mitchell, 1995) and that of change and regeneration (Carmona, 2010) feed hyperbolic thinking and create a too ‘black and white’ picture. Actually, meaning is more nuanced in contexts and more attention in public space research should be paid to really understand the small things of every day life: gestures, smells, trajectories, sounds, comfortable elements and how people interact with them.

Third, urban public space is fundamentally a political space, a space where freedom is negotiated among different groups and the quintessential urban space where difference can manifest itself. In an increasingly privatised world, there has been a resurgence of movements of various groups appropriating space with diverse people expressing their rights, wishes and needs.

Based on this, we found out that the success of many urban development and redevelopment schemes was timing and therefore we pondered on the issue of When is the ‘right time’ for (re)developing a place? It seems that there is no right answer and many schemes become successful for being undertaken in a favorable social and economic climate.

|

|

Read next: Concrete Crusader: Angry Bird

Read previous: Employment Crunch: Hard Lessons

Back to October 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.