Geek\'s Inheritance

24 Feb 2006

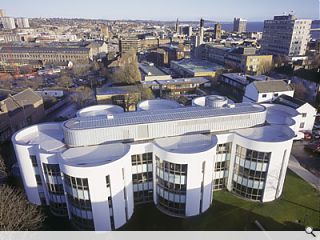

Dundee University’s new master plan ascribed a prime site to the Department of Applied Computing and the Queen Mother Research Centre. The main thrust of a department-wide consultation with architects Page and Park was that the end-users did not want anything ‘geeky’. The response of the Glasgow-based practice was to provide a building which challenged existing work practices arranged around the idea of ‘pods’. At core though, Prospect discovered a reassuring pragmatism. Photography by Keith Hunter.

The world has gone to pods. Whereas modernism gave us a vocabulary of frames and fixed hierarchies, architects and designers have suggested the pod as an alternative ordering experience. As a concept they are comfortably progressive. They are versatile yet familiar. They can be altered and their contents can, indeed should, be changed regularly. David Page, partner in Page and Park uses the word ‘pod’ to describe the central organising principle of the new Applied Computing and Queen Mother Research Centre building at Dundee University. In plan, the pods are most apparent. It looks like a collection of eight distinct and separate units with connecting services; less a building, more an agglomeration of expensive gadgets.

Yet the story of the design suggests otherwise. Poring over the plans on the train from Glasgow to Dundee, Page and Karen Pickering, the project architect, describe how these pods grew out of a special relationship with a unique end-user. “The QMRC works with professional groups to see what their computing needs are. For example, they work with the medical profession on computerised intensive care units,” says Page. The QMRC carries out at research level what it preaches in applied computing at undergraduate level. One of its requirements was for a theatre, which could be used for lectures but also for acting out computer usage scenarios.

These aren’t your average boffins. They are essentially designers. As one of them puts it later: “What we are trained to do is put an end-user at the centre of the design process and find out what they really want, rather than what they say they want.” In addition, Pickering explains that the former department head, Professor Alan Newell, was given a great deal of latitude by the Estates Department to get the building he wanted. It sounds most unlike the world Page recently described in the architectural press. Scotland, he said, was in the grip of “a post-Holyrood conservatism”.

Page sees Scottish architecture as having suffered doubly at the hands of the Parliament. Firstly, Scottish architects were considered too worthy and pragmatic to actually build Holyrood so missed out. Secondly, when the mechanisms that should have delivered the Parliament at a sensible cost collapsed, they felt the brunt again because the image of the profession as worthy pragmatists had been dinted. If it is true, then the work done by the practice at the University of Dundee is thrown into even starker relief. “In a sense [this job] came about during a window of opportunity after the Parliament was commissioned but before the monetary fiasco had a negative effect,” he says.

The building is a delightful piece of pragmatism and will disappoint those whose buttons are pressed by hi-tech architecture. On the train, Pickering draws a rectangle on the plans and says: “This is what we began with.” She introduced rectangular recesses into the block to improve the flow of natural ventilation to a building that would be packed with computers. The practice was told, however, in a day-long meeting with the whole department where favourite buildings were also debated, that they didn’t want “a geeky building”. Bearing that in mind, Pickering began to curve the edges of the recesses. The pods were sculpted from the block rather than imagined separately and then drawn together.

This chimes with the very particular dynamics of the department. “You have to remember that all academics are to some degree autistic, and people who work with computers, well, they’re even worse,” says Newell, wryly and, as it proves, inaccurately. He and the subsequent heads of department, Ian Ricketts and Peter Gregor – they rotate the post – wanted to challenge the stereotypically solitary working approach through the new building, enforcing the idea of collaborative working. A former deputy principal of the university, with jurisdiction over buildings, Newell was uniquely placed to get the “non-geeky” building he wanted. “The last thing we wanted was a regimented office plan with staff patrolling linear banks of students and people e-mailing the person next to them,” he says.

The pods are not the main arranging principle of the building, although they apparently govern the plan and they dominate its façade. Although straight on, the front elevation has a faint feel of the De La Warr Pavilion about it with its white render and railed balcony. However, the side elevations ripple away with comfortable curves rather than austere lines. According to senior staff, the one university building they liked the look of was Cambridge University\'s new Centre for Mathematical Studies by Edward Cullinan Architects or ‘Hawking’s place’ as they term it, given that the mathematician works in one of the seven separate pavilions that form the site. (They don’t, one notes, do pods in Cambridge.)

However, the Applied Computing building should be read as one mass. Most importantly, Building Control offices class it as one continuous office space. Pointing this out is not to detract from the building. It is merely to highlight the very pragmatism that Page believes Scottish architects are no longer trusted for. At a contract value of £4.3 million for over 2,800 square metres, it is good value for a building that is at the heart of the university’s reinvention of itself. Page and Park was initially involved in a master planning scheme to turn the university agglomeration of buildings into a cohesive idea. Farrells, which took up the master plan, want the car park that is currently at the front of the Applied Computing department to become a green that is the focus of the university. As a result, Applied Computing and its new home will become a focal point when landscaping is complete.

The building projects then is not organised around the idea of devolved units. It’s core in fact is a beautifully simplistic double stairwell, which is not only load bearing but a fire stair as well. As a result it has been enclosed with the simple brick construction has been left exposed as the architects wished it could have been throughout the building. The stair wall forms the boundary of the breakout space, which rises the height of the building. Plastered it would be tedious. Covered in art, a distraction. The brick, however, provides the same warming nuance in textural terms that the curving exterior gives in formal terms, even though they apparently have little in common. It is a shame they couldn’t have left the brick exposed. Even the best clients require compromise.

The common Scottish brick from which the load-bearing walls are constructed is not the most hi-tech of materials. The enclosed staircase, however, gives the building a warm core to it as well as bearing its share of the concrete floor plates. Indeed, apart from the reinforcement to this and the bridge over the breakout space, the building has no steel. The floors sit on top of the stair and the pods’ brick walls. Brown’s Construction, a Dundee company, used its own bricklayers. In addition, the joiners have added some simple but quality finishings to the natural ventilation that achieves equilibrium in a tricky environment. The three-storey stretch of brick provides a space to take in the different levels of academia that use the building. From the ground floor one can see the professors move back and forth along a bridge into the research laboratories opposite.

Indeed, the vital division between undergraduates and research students had to be maintained – an element of compromise that you sense Page was disappointed with. In addition, certain members of staff, used to the cellular life of the academic, baulked at the idea of open plan. Newell instructed Page to divide one of the pods on the first and second floor into office spaces. “I knew there would be some people I just couldn’t convince,” says Newell with a shrug. The breakout space though is adequate compensation for losing out on sharing all of the academic space. The caf... has taken its place as a thoughtful alternative to the student union opposite.

Newell and his colleagues, Ricketts and Gregor, are hugely satisfied however. “Everyone is jealous of us. Even the biochemists,” he says with a smile. (The biochemists are considered latter-day alchemists given their propensity to make hard cash from their research.) They are looking forward to seeing what the effects are both in attracting quality students and then subsequently the research they produce. Although Newell considers for a second whether he could create an experiment that would quantify the building’s effect, he admits it is too soon to tell. The building has only been open for one full academic term.

And yet using the building, you can see how it would work. We bump into Ricketts and then Newell by the stair before we meet him in his office. We stand and talk on the more enclosed side of the building, which lacks all sense of ‘podiness’ and has become instead a wide corridor with a large number of adaptable rooms along it. (Some are provided with sliding doors.) Do students not find it difficult to deal with the noise in their new open plan pods, I ask Dr Newell “They don’t seem to have a problem. Most of them have always listened to music as they worked anyway. They’ve got their iPods.”

Read next: The Modernist Ruin

Read previous: Timber

Back to February 2006

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.