Student Housing: Student Calculus

20 Oct 2021

Amid a pivot to online learning we look at how communal living in the student sector must change to meet the needs of a fast-evolving sector. Will today’s digs stand the test of time and if not what needs to be done differently? Has a long-running boom run its course?

The glut of student accommodation delivered in recent decades raises questions about how such buildings may be repurposed as demand shifts and how design can play a role in ensuring the sector can survive and thrive through the uncertain years ahead. With many buildings lying empty as remote learning takes hold, what are the challenges and opportunities facing education?

Rapid professionalisation of the sector has seen the ‘Bottom’-style stereotype of dilapidated digs in haphazard rooms give way to professionally managed blocks drawing hundreds of students together in one building with all the everyday amenities you could need under one roof - and higher rental fees to match. This process has fed interest from overseas students wary of living in a foreign country and stoked tensions from people worried about the concentration of transient populations on their doorstep but is there a ‘right’ mix of accommodation and will recent trends survive the post-pandemic reset?

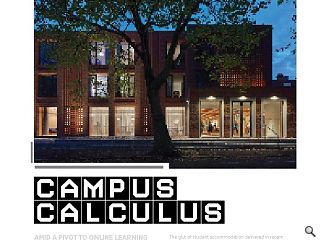

Among those practices with a stake in the future of the sector is Walter & Cohen Architects, fresh from delivering student accommodation for Newnham College at the University of Cambridge. Partner Cindy Walters believes that the future of student accommodation lies in mixed-use developments that are microcosms of the wider city. Stressing the importance of consultation Walters told Urban Realm: “Newnham is all about communal living and consultation was central to the vision for the project.

“In line with good design practice the Dorothy Garrod Building at Newnham is intentionally flexible and includes many design features the students asked for during the consultation; openable windows, direct access to the outdoors, balconies and roof terraces, that have proved invaluable during the pandemic.”

Babak Sasan, director at BMJ Architects, who has experience of delivering a 398-bed student development at 366 Cathedral Street, Glasgow, while at Corstorphine + Wright, said: “I thought it would stop but at the moment the reliance of universities on the sector to boost income is still there. The reason for that is two-fold, 28%-plus of students come from China where the standard lease is 12 months not 10 and students often come with family. Foreign students still view the UK as a top degree destination that is worth more than competing countries.”

Asked about the possibility of converting such buildings for other uses Sassan added: “At a push, halls could be repurposed as a hotel. It’s a night/day difference from when I was a student with well thought out common spaces and airport-style lounges.”

One downside of the push for space has been the rising incidence of deaths associated with students falling from their buildings, including the death of a 20-year-old woman in Wolverhampton over the summer. Sassan said: “Higher than regulation parapets can help, you cannot police everywhere.”

Student housing may be the sector that everyone loves to hate but its attraction for investors, foreign students and universities means it will take much more than a pandemic to pull the rug out from beneath the feet of developers.

Instead, a period of evolution is on the cards as strides are taken to deliver on affordability and attractiveness and self-contained facilities become the norm rather than the exception. In the process student housing shows that it iremains one of the most versatile construction sectors.

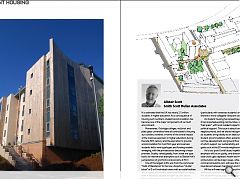

Alistair Scott, Smith Scott Mullan

It is estimated that the UK has nearly 2.5 million students in higher education. As a consequence of housing such numbers, student accommodation has become one of the major components of our built environment.

Monasteries, Oxbridge colleges, red brick and plate glass universities have all contributed to housing our scholars, however, in terms of the overall impact of the massive expansion in higher education during the late 20th century and the aspiration to provide accommodation for most first-year and overseas students led to new typologies and funding models emerging, with the private sector becoming a major provider. Quality varied greatly, from soviet era type bocks to international exemplars such as Steven Holl’s juxtaposition of grid forms and porosity at M.I.T.

One of the largest shifts was from the communal “Halls of Residence” to the now ubiquitous “cluster block” of 5 or 6 individual rooms with en-suite facilities and a communal kitchen, developed in forms ranging from 4 storey courtyards to high rise point blocks. Recent research however has identified a limitation in this model as it can restrict social interaction (particularly with overseas students) and a rebalance towards a more collegiate viewpoint seems likely.

As student housing has spread beyond the campus it has impacted existing communities, often gaining a “bad press” with local residents objecting and mustering political support. This issue is about balance within a neighbourhood, and we should recognise that not only do students bring vitality to an area but as a typology student accommodation offers advantages of density, car-free development and ground floor facilities, all of which support our sustainability and place-making goals such as the 20-minute neighbourhood.

As to our post-Covid future, hopefully, the next emphasis will be on quality, and diversity of type as older stock gets replaced. Health and wellbeing and online tuition will be major issues, while the rise of commercial build to rent, will have the impact of blurring boundaries between mainstream and student housing.

All this will need significant input from the design professions, and we must not lose sight of the key role that student housing plays in allowing our young people to gather, socialise and build the aspirations that will shape our world in the future.

|

|