The Barbican Centre: Vertical City

15 Apr 2020

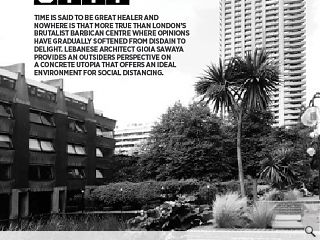

Time is said to be great healer and nowhere is that more true than London’s brutalist Barbican Centre where opinions have gradually softened from disdain to delight. Lebanese architect Gioia Sawaya provides an outsiders perspective on a concrete utopia that offers an ideal environment for social distancing.

Located in the heart of London, the Barbican Estate by Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon architects extends beyond being a remarkable example of brutalist architecture.

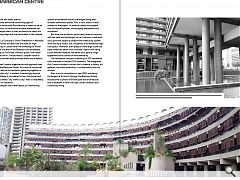

If we talk about solids and cavities in architecture, scale and proportion, rhythm, structure, and balance, the architecture of the Barbican Estate is clearly composed of space and character. The character of its space is composed of the material consistency of elements and their formal appearance. But, since most people judge the external appearance of things; or in other words, their “aesthetics”, it didn’t come as a surprise when the Barbican was voted “London’s ugliest building” in a poll in London in September 2003. Opinions about its design have always been controversial. The project itself has always proposed to emphasize the opposition, focusing its attention on defining a self-contained urban microcosm based on variations that alternate within a strict regularity.

This approach to achieving a character of the place in contrast to what’s existing gives the Barbican Estate an aspect of an ordered complexity, leaving the space to the preeminence of creating itself a great spatial richness, where repetition and order coexist.

Here, a bolder and more resounding type of architecture is introduced. Architecture is meant to be an expressive space, so the architects were interested not only in how people react to their architectural ideas, but also in how they adapt and use these ideas in the created environment.

Similar to Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Marseille, Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon saw the need for high-density housing in London after the bombings of World War II that left the area of the Barbican site devastated.

Inspired by Le Corbusier’s famous quote “the house is a machine to live in”, the architects’ utopian vision to transform this bombed area provided them with a radical opportunity.

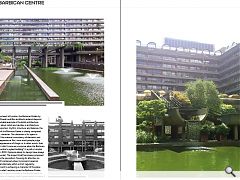

Le Corbusier’s spatial organization and approach was replicated in the Barbican Estate. His vision of communal living and his idea of the residents gathering together in a “vertical garden city” is evident. Interestingly enough, the Barbican Estate is considered to be a functional and spatial unique walled “city within a city” that is completely optimiSed for its residents.

With its complex multi-level layout, an interlocking system of residential blocks is arranged along with outdoor communal spaces. This, in turn, adds a visual interest to the project. In addition, patios incorporate into the façade systems, encouraging exploration and movement.

But what the architects particularly share in common with the work and philosophy of Le Corbusier is that both use a grid that adopts a proportional measuring system, while having a mixed- use, modernist, and residential high-rise aspect. Moreover, both projects were large-scale and used reinforced béton-brut concrete. Apart from being a cost-efficient material, the béton-brut gave a rough appearance and a sense of monumentality.

The residential complex is made up of 2113 residential units intended to house 6,500 residents. The integrated Arts Centre includes a concert hall, a theatre, a library, art galleries, bars and restaurants, a conservatory and two schools.

Ever since its completion in year 1982, and being the largest of its kind in Europe, the Barbican Estate has become a symbol of British post-war architecture and a landmark in terms of scale, social cohesion, and community living.

|

|