Social Housing: A new golden age?

13 Jan 2020

Social housing is enjoying something of a renaissance as a new breed of public housing reshapes our cities but will today’s buildings stand the test of time? Part II architecture student Marie de Bryas examines the recent evolution of the sector.

As we are celebrating the 100 years of the 1919 Addison Act, the first governmental incentive encouraging the construction of councils Houses across the UK, Scotland finds itself in a new turning point in defining what social housing looks like. The government’s goal of building 50,000 new affordable homes before the end of the parliamentary term is the highest since the 70s, and the latest reports account for good progress. However, as the challenges we face evolve, designers cannot recycle yesterday’s solutions. So how are architects facing the new problems of today and are we building at a sufficient quality to stand the test of time?

Scotland has a long track record of building affordable housing, dating all the way back to the 19th century, and is currently extending this heritage. But as the world is evolving, Architects are constantly asked to rethink the housing typology to face new challenges. The Scottish Government, along with ESALA, Collective Architecture, and Peak15, are in the process of organising “Housing to 2040”, a travelling exhibition that will set up a “conversation about how we can together plan for what we want our homes and communities to look and feel like in 2040”. As such, they highlight several new challenges that architects will face in the future. The main ones are the need to mitigate the impact of climate change through design and the all the consequences of Scotland’s ageing population. The latter causes designs to promote greater adaptability to allow living at home for longer, reducing the demand on health care.

When examining what is currently being built in Edinburgh, one can clearly see the shift of priorities that is happening in the housing sector. Some designs are finding elegant ways to address these issues.

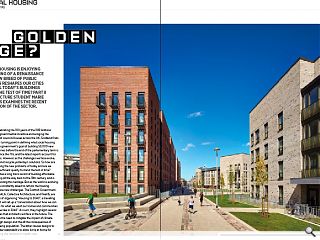

In their new Leith Fort development, Collective Architecture (along with Malcolm Fraser Architects who obtained the planning permission for this project before they ceased trading) decided to update the historical typology of the Colony houses. This historical precedent allowed them to focus on accessibility and social diversity whilst respecting the site’s identity.

Colony houses appeared in the second half the 19th century in Edinburgh and were originally built for artisans and skilled working-class families. Traditionally, a colony house would be divided into two flats, upper and lower, with a front door on opposite sides of the property, allowing both flats to have a font garden.

The Leith Fort development has reinterpreted the concept with a ground floor single storey flat and a 2-storey duplex apartment above it. As such, all of the ground floor flats (accounting for 50% of the housing) are accessible and barrier free.

Moreover, the compromise between density and amenity space ensures a dynamic neighbourhood. The design encourages interaction within the community thanks to a shared green space as well as private garden layouts. By placing both gardens side by side, Collective Architecture ensured all gardens to be south facing and promote a dialogue above a shoulder height separating wall. On the other hand, the opposite front doors maintain a sense of ownership and privacy.

Collective Architecture and Malcolm Fraser Architects offer an elegant design and fully address the aging population issue highlighted by the Scottish Government. Their reinterpretation of a historical typology proves to be relevant and will hopefully inspire other designs.

The project has gotten a lot of attention and received several prestigious prices, but is it a good representation of housing projects in Edinburgh? Or are we using the one successful project as a distraction from the other unsuccessful schemes?

The Edinburgh council is currently doing a lot to deliver enough housing. Through the “City of Edinburgh Council 21st Century Homes”, the council is currently building numerous projects, and has committed to deliver 20,000 new homes within a decade.

This is possible partially thanks to the Small Site initiative, which encourages smaller disused land to be transformed back into productive use. This concerns the North and West of the City and has been in place since 2016. A few developments have already gotten planning thanks to the program allowing redevelopments in old industrial areas to be easier.

Such strong commitments are to be celebrated. Shelter Scotland welcomed the Scottish government’s efforts, particularly the “funding suggestions on empty homes; reform of Right to Buy; streamlining regulation of private renting and commitments to security of tenure for tenants”. Though, we must remember numbers are not the only issues we face.

It seems; however, the focus is not just put on quantity. The “Homes fit for the 21st century” program, started in 2011 by the Scottish government, had ambitioned to also “improv[e] design and greater energy efficiency in housing” by December 2020 in order “to reduce [Scotland’s] energy consumption by 12% and its greenhouse gas emissions by 42%”. A 2014 report shows that considerable progress has been made but needs to be continued.

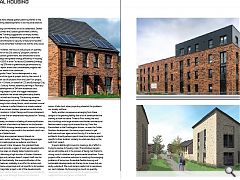

The Craigmillar Town Centre development is very representative of the type of project built by the council. It uses a different set of solutions from the Leith Fort project. Anderson Bell + Christie, on behalf of CCG and Edinburgh City Council’s 21st Century Homes obtained planning in February 2018 for the development of 194 new residential units.

The housing project is part of a bigger masterplan designed to transform the whole area particularly thanks to new retail, schools and housing. The housing scheme focusses on delivering a rich mix of different density, from terraced housing to four-storey blocks, which ensures a social diversity. The scheme is unified thanks to a simple material palette as well as corners markers, placed across the site to highlight key locations. In their Design and Access statement, the architects note that an emphasised was placed on “strong forms and massing”.

Unfortunately, this leads to a feeling of oversimplification of designs. The lack of architectural features on the facades reminds us of 1960s housing developments, known for having a tendency to feel very unpersonal to the residents which can cause feelings of detachment.

The dwellings are organised around shared car parking and semi-public pathways. This layout encourages overlooking to create passive surveillance, and thus is intended to prevent crime. However, the grassland feels anonymous and reminds us again of post-war developments.

The scheme relies on already tested solutions and is successful in delivering a high number of houses. However, it feels nostalgic and perhaps doesn’t project itself into the future enough. Aesthetically, the oversimplification of the architectural features, probably in an effort to reduce cost, makes the scheme unpersonal and not specific to its location.

Like the Craigmiller project, a lot of the developments from 21st Century Homes focus on achieving a social diversity whilst reducing crime. Although they are two important issues, it falls short when projecting ahead at the problems our society will face.

Sadly, another consequence emerging from these designs is the growing feeling that a lot of development are starting to look the same. Three to Four storey, flat roof, brick buildings with large windows and limited architectural features seem to pop-up all around the city. From the Prestonfield to the Duddingston homes, or even the Calder Gardens development, the same project seems to get built over and over again across the city. It is a shame and architects should perhaps spend more time making projects specific to their location, similarly to what was done on the Leith Fort project.

It seems Edinburgh’s council is making a lot of effort in trying to resolve its housing crisis. The ambitious targets set are admirable and in the process of being met thanks to strong council initiatives and governmental incentives. Some projects offer innovative solutions to resolving the emerging problems of tomorrow. Accessible flexible housing and sustainable developments are the key to our issues but are sadly underbuilt. We must remain careful not to reproduce our past mistakes. By focussing too much on quantity, developers and council take the risk of creating soulless neighbourhoods and generic architecture.

|

|