Middle East: War Bonds

23 Apr 2019

War has brought incalculable human and physical losses to the middle east but the process of regeneration is already underway. Jaromir Gasiorek, senior architect at Smith Scott Mullan and Krzysztof Chuchra of Edinburgh World Heritage discuss how conservation and energy efficiency expertise gleaned at home in Edinburgh, is being applied in Turkey to help restore and protect what remains of the regions priceless architectural record.

Armed conflicts kill, destroy and destabilise. They target people, their culture, identity and heritage. The last five years have witnessed the destruction of ancient monuments in Syria and Iraq, including Palmyra - one of the oldest and best preserved cities in the world, blown up and looted by ISIL in 2015 - and many other significant monuments across the region.

It is clear that local communities in all affected countries will need support to re-build themselves and to restore and protect whatever is left of their tangible and intangible heritage. In response, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the British Council launched the Cultural Protection Fund in 2016. It resembles UNESCO’s World Heritage in its ethos, but with an added emphasis on sustainable development.

Turkey became one of several countries eligible for the Fund’s support due to instability caused by the proximity of the war in Syria.

In 2017, a partnership between Edinburgh World Heritage (EWH) and Kültürel Mirası Koruma Derneği (KMKD) from Istanbul secured £1.3million of grant assistance from the Cultural Protection Fund for a capacity-building project in the region. The project is called KORU (“protect” in Turkish) and located in two of South East Anatolia’s cities – Mardin and Antakya. KORU builds capacity in heritage management and conservation, and also brings considerable innovation. Its programme is focused on four pillars:

- Surveying and documentation of buildings at risk

- Community engagement, learning and training on building conservation and heritage management

- Sustainability of historic sites

- Safety in historic sites affected by conflict.

Smith Scott Mullan Associates teamed up with EWH to address the challenges of the ‘sustainability of historic sites’ presented by a major component of the KORU project, the restoration of a traditional tenement in the historic core of Mardin.

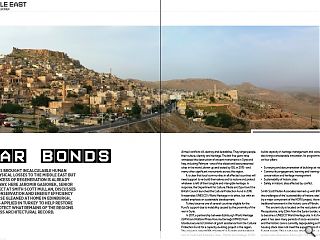

This ancient city is located on the vast plains of Mesopotamia, only 22km from the Syrian border, and hopes to become a UNESCO World Heritage site. In its four thousand years it has seen many periods of socio-economic turmoil and the historic core is currently depopulating as the historic housing stock does not meet the expectations of modern Turkish society. This is not a new phenomenon – a similar exodus was observed in Edinburgh’s Old Town in the 1950-60s and is still happening on a massive scale in China. Residents of old Mardin prefer the comfort of the contemporary but characterless blocks of flats being built in the new part of the city, which resembles post-war development in the Soviet Union. The typical old stone houses, although charming, struggle to meet basic functional needs and are difficult to maintain. Heating in the cold desert winter and cooling in the extreme heat of summer can be very challenging due to both fuel poverty and technological flaws. The conflict in nearby Syria, which resulted in significant emigration to the European Union, has exacerbated the problems by affecting the tourism on which the local economy relies.

The Tamirevi project, Turkish for Restoration Lab, is an ambitious attempt to awaken the imagination of practitioners and decision-makers by combining all of KORU’s pillars in an exemplar building restoration and a programme of engagement activities that open the project to the local community. Tamirevi was left by its owners under the care of the Museum of Mardin, which plays an unusual double role of local museum operator and enabler of heritage-led urban revitalisation. The refurbishment must not only meet the conservation standards of an aspiring World Heritage site but must also represent state-of-the-art energy efficiency design. This was KORU’s aspiration from the outset, but EWH found that energy design expertise was not readily accessible in Turkey and so sought an experienced advisor in Scotland.

Smith Scott Mullan Associates’ role, as Energy Efficiency Advisor, was to analyse the building construction and its siting in the context of local common practice and to make recommendations for improving energy efficiency. The final design, informed by Smith Scott Mullan Associates’ commentary, is currently being developed by KMKD’s and EWH’s architects. The challenge is to achieve the highest standards of energy efficiency while taking into account local conservation and statutory restrictions and the availability of materials, systems and skills.

Sharing the knowledge obtained during this architectural experiment is one of the key objectives of the project and, on completion, Tamirevi will house an exhibition space where the results will be presented. It will be a creative learning space in the city as well as an excellent energy efficiency education hub for local residents. The use of the upper floor as an artist’s residence will ensure the financial sustainability of the project.

Technical approach

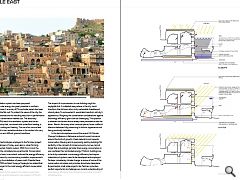

Tamirevi is a simple two-storey cubic stone house with a courtyard. It is separated from the street by a single-storey arcade opening onto the courtyard. The adjacent buildings are variations of the same typology, and together they form an irregular terrace. The structures are embedded in the hill against caves carved from the bedrock which are traditionally used for storage.

The entire city faces south with almost no soft landscaping or foliage and despite the buildings’ thermal mass, summer overheating is severe. One of the Turkish team described the house, during the summer months, as turning into an oven. To mitigate this, a folding canopy and the planting of a tree, providing shade to the south elevation, have been proposed. Similar planting throughout the old city would improve its microclimate through more comprehensive shading and evaporative cooling, but would have a profound effect on the city’s appearance.

U-value improvements address summer overheating and winter heat loss. As in Scotland, insulation could readily be added to the roof and ground floor. Improving the external stone walls was more difficult due to the conservation restrictions and the only permitted intervention was to eliminate draughts by re-plastering the interior with a site-specific lime plaster specified by KMKD.

The windows will be replaced with the locally-made double-glazed windows based on the original design, for which the Museum of Mardin’s workshop is currently producing a prototype. It will create a sustainable alternative not only for Tamirevi but the rest of the city, while local carpenters will learn about new technology.

In heavy autumn rainfall, the maze of lanes and stairs turns into rivers and waterfalls. The introduction of green or blue roofs was explored but proved to be impracticable, again, due to conservation constrains and the roof profile amid concerns around the appearance of the wider city landscape.

The concept that good, energy-efficient design should use building physics to minimise or preferably design out M&E installations was the driving force behind Smith Scott Mullan Associates’ advice. They considered the use of under-floor ducts to pre-cool incoming air. The constant underground temperature of 8°C and the constant 18°C in the cave would provide efficient and free cooling, thereby using the unique site conditions to provide a comfortable interior environment with minimal energy use. Unfortunately, due to ground conditions, under-floor ducts proved to be impracticable. For the efficient heat transfer of the system, soil requires certain levels of saturation, a condition that could not be satisfied by the rocky, hard and dry soil in Mardin. The current design still benefits from the constant temperature of the cave through the location of the incoming air ducts. Ventilation requirements for the exhibition space led the design team towards the use of mechanical ventilation and the experimental use of a heat recovery ventilation system has been proposed.

Naturally, solar energy has great potential in southern Turkey. To harness it, an array of PVs and solar panels has been proposed for the flat roof. To protect the views of the city, the panels are horizontal and the resulting reduction in performance accepted as a conservation-related cost. The electricity produced by PVs feeds the ventilation system and the air-source heat pump that, combined with underfloor heating, is used for both cooling and heating. The use of air-source heat pumps proved to be a suitable solution in the context of a very tight urban form and difficult ground conditions.

Conclusion

The ideas and technologies employed in the Tamirevi project are largely unknown in Turkey, even less so when forming one interconnected, holistic system. With this in mind, the project should be considered as experimental. Conservation considerations have, to an extent, reduced the energy efficiency of the final scheme by compromising insulation improvements and precluding the installation of green roofs. Despite these challenges, KMKD architect Sureyya Topaloglu has stated that the Tamirevi project is the most energy efficient conservation project in Turkey.

The aspiration for the project is to create an exemplary precedent that could be followed by the residents of Mardin. The impact of improvements to one building might be negligible but, if multiplied everywhere in the city, could transform the old town into a truly sustainable, liveable and vibrant place. To some extent it would also transform old city’s appearance. Weighing the conservation considerations against the energy efficiency gains can be challenging. The question is whether the former should always take precedence over the latter. Mardin, like many other historical places, faces a difficult dilemma between fully preserving its historic appearance and being practically habitable.

In the dark atmosphere around the recent UN Climate Change Conference in Katowice and amid current concerns around the limits of growth, it feels natural to turn towards conservation. Reusing and re-purposing existing buildings fits perfectly in the concept of circular economy, but we cannot forget that as buildings get older their energy consumption in use overtakes their embodied energy. If historic buildings are to be truly sustainable, more energy-efficiency techniques, materials and systems need to be developed and employed. Perhaps, considering climate change, a review of some of the conservation principles and priorities should also take place. Experimental, small scale projects, like Tamirevi, provide a perfect opportunity to challenge our current understanding of what energy efficiency in conservation is and what it could or should become.

Authors:

Krzysztof Chuchra - International Programme Project Manager at Edinburgh World Heritage

Jaromir Gasiorek – senior architect as Smith Scott and Mullan Associates and Energy Efficiency advisor Tamirevi project

|

|