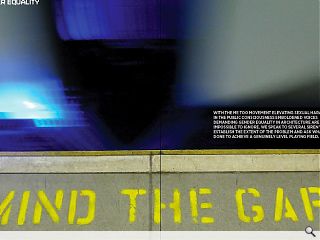

Gender Equality: Mind the Gap

17 Oct 2018

With the MeToo movement elevating sexual harassment in the public consciousness emboldened voices demanding gender equality in architecture are becoming impossible to ignore. We speak to several siren voices to establish the extent of the problem and ask what can be done to achieve a genuinely level playing field.

Successive attempts to modernise the architectural profession have been met with indifference at best and active resistance at worst but with the RIAS itself in the throes of change progress might finally be on the cards.

One of the loudest voices championing change is Collective director Jude Barber, a founding member of campaign group A New Chapter. Explaining her motivations Barber said: “As a feminist I believe in equality for men and women. We don’t yet have a healthy gender balance, or a level playing field for women in architecture, which is why a degree of campaigning and activism is still required. The reason I’ve become more vocal in this field is because when I looked out over the parapet I was struck by the pervasive sexist, at times misogynist, behaviour within the industry at large. Women have been swimming against the tide in many areas of their professional life for too long.

“Recent statistics and growing evidence indicates that women’s work is less valued financially, less well documented and women are less likely to be invited to speak publicly about their work.”

In an effort to turn the tide Barber is speaking out as co-host of Voices of Experience, an Architecture Fringe project aimed at sparking informed discourse on the range, depth and output of female architects. Barber suspects that the deep rooted notion of the ‘singular voice, author and designer’ is at the heart of much of this under representation, a self-fulfilling bias that pervades architectural training, literature, archives and the press to such an extentand is so deep rooted in our psyche that it is exceedingly difficult to break out of, particularly in a society in which men still claim the greatest media authority. Leading by example Barber points to the team accomplishments of Collective where the office has striven to shatter the myth of the singular genius. Barber explained: “There is no such thing. Any idea is born from coming together, listening, reading, talking and chance opportunities.”

Far from an improving situation Barber believes that social mobility is actually getting worse, with serious consequences not only for women but also ethnic minorities as financial pressures constrain routes into the profession. For now though there remains a steady stream of women graduating from our architecture schools. As Collective architect Mairi Laverty, pointed out: “It doesn’t seem to be a challenge attracting women to study architecture. When they leave as young graduates its actually still well balanced, it’s what happens ten years later. That’s where there’s a big drop-off.”

Of course these issues shouldn’t come as a shock to anyone with Barber clearly recalling a 2012 mission to the RIAS with her colleague Cathy Houston in a bid to break the logjam, only to return despondent after meeting not just indifference but active ‘resistance’ to their reform agenda. Barber continued: “While the RIBA has championed ‘Women in Architecture’ and ‘Architects for Change’, our institutions haven’t yet taken a lead on the issue of representation. Instead, media-led activity such as the Architect’s Journal campaigns.

Putting forward her own manifesto for change Houston said: “The only way to true equality in the workplace is to equalise rights across the board that includes the amount of parental leave both men and women are entitled to. You still hear of people losing their jobs during maternity leave and I find it really odd that that can still happen in this day and age.”

As well as official channels frustrated women have been forced down more modern avenues of protest, as evidenced by The Shitty Architecture Men list which has been doing the rounds online. It may seem shocking, but Barber is far from surprised: “One of the items I found interesting thing about the AJ Women in Architecture survey was that women faced greater levels of harassment in their studio environments over their experiences on site.”

Nicola McLachlan, also of Collective, added: “I am a young female architect, and I now ask myself questions regarding the nature of our profession which I wish I had pondered sooner: Who are architecture’s role models? Who are we taught to respect, and aspire to be, over the course of our architectural education? The answer is male architects: more often than not, exclusively so. “I have noted as a practising architect that our language is still geared towards accrediting one sole (usually male) architect for the realisation for a project; this has never, and will never, be the case.”

One organisation seeking to make a difference is Women in Property, which aims to increase the number of women in managerial roles via mentoring and its own ‘mid-career task force’. Outlining these initiatives Lynsey Brydson, chairman of the Central Scotland branch of Women in Property and head of business development at City Building Engineering Service, said: “We advise businesses on recognising unconscious bias which is often entrenched in an organisation. We help businesses understand the challenges women face around mid-career, which is when many of them drop away from the industry, the benefits of mentoring and providing a clear career path. But this is not just about women; very many of the issues that affect women are very real for men too, not least of which are flexibility, work-life balance and career progression.”

An oft-cited requirement to bridge the gender gap is a greater number of role models and flexible working, Brydson said: “This is about a pipeline, from school, right through to the board and change needs to happen at a very early stage. Primary school children are already starting to form gender judgements. Take this forward a few years and we have a generation of school children who are very likely not to have encountered the many and varied disciplines our industry offers, unless they have a parent or family friend who can advise them.

“In Building a Better Workforce (a survey compiled by Women in Property, Gapsquare and Rosemont Partnership in 2017 from property and construction industry respondents in the South West of England), only 16% said that their role was flexible, yet it was cited as being the overwhelming work benefit of choice. Having this flexibility, alongside a clear training and development programme makes the employee work more efficiently and productively as well as strengthening their loyalty to their employer.”

Isabel Garriga, newly elected president of Glasgow Institute of Architects, has pledged to use her mandate to champion ‘true equality’. Born in Spain Garriga arrived in the UK to study in 1995, welcoming the tolerant university environment where the only barrier she faced was language. Speaking to Urban Realm Garriga said: “I found it really hard because my English was bad. But I like working and I like working with people who are very opinionated. I am very sociable but also very opinionated and some people don’t like that. I’m really loud, you’ll hear me. Making me shut up is the hardest part.

Outlining her equality crusade Garriga added: “I’ve had issues where I’ve gone to building sites and I’ve heard something slightly inappropriate like ‘knickers’ and I’ve looked at the guy and said ‘don’t call me that ever again’”. Despite such instances Garriga believes the working environment here is politer and more respectful than back home, saying: “There are less arguments. There were only three of us working together in Spain and you could hear the screaming from outside the office! One of the reasons I’ve stayed here is the working conditions are much better.” Illustrating that difference Garriga points to a recent scandal in her home country: “In Spain there was a huge scandal because a woman was raped. It went to trial and they got a guilty sentence but got it reduced because apparently she looked like she enjoyed it. That caused people to go crazy and take to the streets to point out that rape is rape. I think the #MeToo movement is important for all women.”

Asked what measures she would like to see introduced to help level the playing field further Garriga said: “I wouldn’t like my boss employing people based on gender. Women should have an equal chance but they should be selected on the contribution they can make because then we’d go back to being flower pots or decorations for the table. We’ve got to be talented to get the job. More flexible working would help, we have a level of that in our office. Sometimes with the pressures of deadlines and big projects it does not help when people work part time, one day a week in the office.”

Despite the challenges Garriga has observed real change during her career, saying: “Compared to when I first started in work 15 years ago there are now way more women not just in architecture but across the construction industry. In the future I would like to see women have not just equal chances of getting the job but equal pay. Nobody ever knows what someone else is earning or why you’re an associate director and not earning the same. I would like more transparency.”

Architects take pride in belonging to a liberal profession selflessly toiling for the betterment of society but in projecting this idealism into their work the danger is there is little left to tackle the internal schisms which are now all too painfully apparent. If that altruism is to truly build a better society then the bridge building must begin at home.

Missing in Action: Julie Wilson

When I studied architecture back in the early 1990’s the proportion of women in the architectural profession was 13%. Three decades on and that figure has risen, but only slightly to 25%. As a profession we need to be taking a long hard look at ourselves and questioning why this figure is so low? If other countries can achieve a gender balance in architecture, why can’t we? There are clearly still deep-rooted problems which are causing woman to drop out of pursing a lifetime career in construction. I have heard men trivialise this by saying, “well woman have babies”, but it is about much more than just the child bearing years. It is about a culture of sexual discrimination, harassment, bullying, having your intelligence and technical ability questioned, lower pay than male colleagues for the same job, lack of career opportunities and advancement. For anyone who doubts how bad things really are, the AJ 2018 Woman in Architecture survey makes a sobering read.

I teach first year studio at ESALA where the proportion of female students commencing architectural studies is equal to male. Each September we meet a new group of bright, intelligent, talented female designers, with high aspirations of a future career as architects. Nationally by the time students are working towards their part 3, female numbers start to drop. These are woman in their twenties, not necessarily thinking about parenthood yet, who are deciding that architecture is not for them. Why? Such a loss of talent and aspiration. A loss to society as a whole.

Much can be done to prevent this happening. I would like to see the Scottish profession collectively launch a 50:50 campaign with a target to achieve gender equality in architecture. Bullying and misogyny in the workplace needs to be called out. Colleagues need to actively speak up if they witness this behaviour, and an environment needs to be created where help can be sought without career persecution.

The logical driver for a 50:50 campaign is our national professional body the RIAS. For many years nick named “the old boys club”, where 91% of those awarded the special accolade of Fellow are male, the Incorporation is going through a process of reform. For the first time, three out of the six RIAS Chapter Presidents’ are woman (myself included). Female voices are getting heard, although many more are needed.

The RIAS should look to set up a mentoring scheme, similar to the RIBA Fluid programme developed to address under-representation within management and leadership structures. Students and newly qualified architects should be provided with support to learn how best to thrive in a competitive, commercial environment. Mentor help for female architects, at critical turning points in their careers, to encourage them to continue in the profession, or to return to work after extended leave, should finally see the 25% figure start to rise. Scotland’s built environment can only benefit from retaining all that creativity, enthusiasm and talent, that I see each September with the new intake of young female students entering the first-year studios.

Julie Wilson is a Partner at Brennan & Wilson Architects, part-time design tutor at ESALA and President Edinburgh Architectural Association

|

|