Sixteen Church Street: Dumbarton Rocks

17 Oct 2018

With High Streets under greater pressure than ever West Dunbartonshire Council are seeking to turn the tide by relocating hundreds of staff to Dumbarton town centre. In doing so they have not only rejuvenated a local landmark, but shored up the town centre and given fresh impetus to its waterfront regeneration. We discover why contraction can be the best form of expansion. Photography by Jim Stephenson.

At a time when some towns are experiencing the movement of public institutions to their peripheries, such as Hamilton’s loss of the University of the West of Scotland to its outskirts, West Dunbartonshire Council has laid down a symbolic and physical statement of intent by relocating 500 staff from its crumbling 1960s outpost at Garshake to the heart of the town, with knock on effects already being felt on the once struggling High Street.

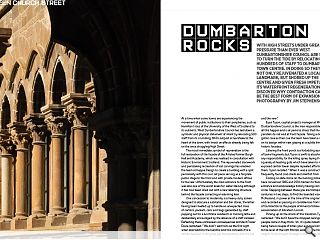

The most immediate symbol of rejuvenation is the full restoration of the facade of the A-listed former Burgh Hall and Academy, which was realised in consultation with Historic Environment Scotland. The rejuvenated stonework and painstaking recreation of lost carvings has enabled the team at Keppie Design to create a building with a split personality with this civic set piece serving as a fairytale public stage to the front and with private modern offices to the rear. Unfortunately the main entrance to the front was also one of the worst areas for water staining although it has now been dried out with a new retaining structure behind the façade correcting an alarming lean.

One concession to modernity is a heavy-duty screen designed to obscure a substation and bin stores, the latter having been beefed up to handle an unexpected mass of cartons, packets, cans and bags generated by staff popping out for a lunchtime sandwich or morning latte and deliberately encouraged by the absence of a staff canteen. Reflecting these unforeseen consequences architect Fraser Davie remarked: “We didn’t want bins as the first sight when approaching the building and this conceals it to a certain level but it still gives you transparency with the old and the new.”

Euan Tyson, capital projects manager at West Dunbartonshire Council, is the man responsible for making all this happen and is at pains to stress that the historical parallels do not end at front façade. Taking a decorative gothic rose as their cue the team have taken a modern riff on its design within new glazing as a subtle link with the historic facades.

Littering the front porch is a forbidding assortment of bone fragments but Tyson is swift to absolve staff of any responsibility for the killing spree, laying the blame squarely at feasting gulls which have taken to nesting in the exposed central tower despite repeated efforts to dislodge them. Tyson recalled: “When it was a construction site we frequently found crab shells and shellfish from the Clyde.”

Finding no date stone on the building stonemasons have carved out 1865 and 2018 markers to flank the front entrance and acknowledge history having come full circle. Stepping between these you are transported two centuries in two steps, to find the bearded visage of provost McAusland, in power at the time of the original construction and recorded as passing on condolences from the people of Dumbarton to the people of America following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Picking up on the shock of this transition Tyson remarked: “We don’t have the dropped ceilings and when people come in they think, ‘oh, it’s quite industrial’ but after being here a couple of times your eye level comes down to the level of the light fittings, enabling the historic floor heights to be brought through to the new build sections.” More intimate meeting spaces sport suspended acoustic baffles that give the impression of a standard ceiling height, while still allowing floorplates to tie-in with the front.

New build elements are faced in brick with large format frameless windows maximising views and light as Davie’s colleague, fellow architect Neil Whatley, explained: “The extension is a really simple and restrained building. One of the key gestures is a recess at the upper floor. If we’d gone in at three storeys it would have been a very awkward junction with the old building. The whole building is very frugal and honest in terms of exposing the concrete frame.”

A thumb print security system serves as the frontline defence for the inner private core of the build while panic alarms provide staff with a sense of security should anything go awry in their dealings with the public. Tyson remarked: “You’ve got a public space, an invited space in the base of the atrium and public gallery with a second line of security to the private space. In Garshake we had separate receptions at every far-flung corner and security issues with members of the public able to meander through the building.”

The project almost came unstuck before it began when Dunne Group, who had previously been awarded the superstructure package, went into administration just prior to the signing of contracts, delaying works as this element was re-tendered to Careys. Davie continued: “We worked very closely with the concrete subcontractor to create chamfer corner details to accentuate the columns and floorplates. It’s a post tension frame so there are tendons running through the concrete so it’s quite a specialist system but it keeps the mass of the concrete down.”

On the back of the hottest summer in half a century the naturally ventilated building faced a literal baptism of fire but has largely accredited itself well in the face of rising temperatures. Fraser said: “As part of the natural ventilation strategy incoming air from the automated and manual opening windows is expelled through exhaust louvres to the north and south, with one set closing depending on the wind direction. It’s a perforated acoustic ceiling but also we got the felt backing removed to allow the air to flow through.”

Acoustic panels, designed by Danish practice 3XN, are a feature throughout, helping to absorb stray sounds within the open plan spaces. Tyson observed: “You’ve got a timber balustrade and glazed screen with people working the other side but you don’t actually hear any background noise.”

A secondary rear entrance offers direct access from the car park where the office component steps out in order to maximise views of Dumbarton Rock, which is in process of being integrated with the town by means of a riverside walkway. These views are framed by deep-set walls with perforated metal panels to minimise heat gain. Weather permitting outdoor benches carved from historic roof trusses provide a secluded spot from which to soak in the surroundings and is already a popular spot for skateboarding.

Learning lessons from their experience at Ronald McDonald House in Govan Keppie were quick to allocate a laborer solely to mixing incoming palettes of bricks to ensure an even appearance across the facades. Whatley said: “The deep piers are a pragmatic response to the orientation and keep as much glazing as we can without overheating. Internally we’ve accentuated by pulling the piers in. New stone ties in with the brickwork. In four years, it will be almost indistinguishable from the old.”

Gesturing to some newly acquired silver hair Tyson recalled a second major incident which threatened to quite literally sink the project, the unexpected discovery of a forgotten gas tank beneath the present car park. “We were removing trees and one came down and punctured the lid of a 14m diameter gas tank full of contaminated hydrocarbon gunk”, recalled Tyson. “It took about 16 tankers to empty.”

A key requirement of Historic Environment Scotland was the recreation of rooftop dormers, despite the fact that the attic floor is not utilized but rather extends the volume of the main council chamber. Whatley explained: “It was important that we didn’t have any dummy features, so the dormers have been positioned to bring light into the building and provide an active frontage. We wanted to express the volume but also had to be quite pragmatic with structural issues as well, acoustically it works really well.”

Each office floor is a close mirror image of the floor below with a slight setback on the upper level. Organised with a ratio of ten staff to six desks, with individual lockers provided, the spaces are arranged logically with desks rubbing against solid elements, with gangways opening to glazing. It contrasts with many fully glazed city centre offices where desks abut directly against glass. This economical allocation extends to the chief executive herself who is based at a spartan open plan table which doesn’t even have monitors installed. Tyson added: “The transom on the windows is 1,100 high but we made it 800 so you can see out while sitting down.”

Evidencing the sort of random encounters fostered by an open plan layout Richard Cairns, strategic director for regeneration, environment and growth, appeared for an unscheduled chat. A favoured conversation piece of Cairns is a time lapse video charting construction of the new HQ but it is the background demolition of a 1930s distillery tower which gets him truly animated. Now earmarked for 155 homes Cairns is proud to have played a role in felling the landmark, noting that the project was only confirmed after the council confirmed its move. Added to the opening of a new Costa Coffee it seems that Dumbarton’s fortunes are now on the turn. As Cairn said: “In one sense you’re here too early. I’ve asked the planning department to do an annual High Street census. There have been three new lets since we moved in and one of the café’s has been completely refurbished. We could have built a less expensive building more quickly and easily almost anywhere else in Dumbarton but we took the decision to come here because the value add for us wasn’t the operational costs in here but the benefits out there.

“We were in a not fit for purpose, oversized, poorly located property. We’d built up a backlog of maintenance which ultimately would have crippled us. We’ve moved out into a building that’s a third of the size, saving £400k a year which allowed us to roll out a range of modern working practices. Electric pool cars outside have reduced our petrol mileage by 40%.

It changes people’s perception of who they work for and their understanding of who they work with, because they can see them. In Garshake you knew there were people all over the place but you didn’t know who they were or what they were doing. Not only can you see people working in the new offices but you can now see groups of people, giving you a different understanding of who interacts with who.”

Openness and transparency are the watchwords of any public authority and with their move to the heart of Dumbarton West Dunbartonshire Council lead the way on both fronts. Having come full circle the move has already seeded development far beyond Church Street, indicating the nurturing role the public sector can still play in these times of austerity.

|

|