Architecture in Crisis: Rotten Burghs

11 Jan 2017

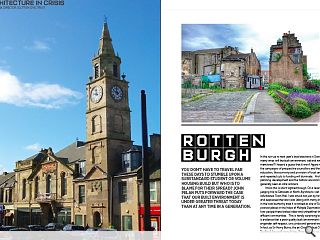

You don’t have to travel far these days to stumble upon a substandard student or volume housing build but who is to blame for their spread? John Pelan of the Scottish Civic Trust puts forward the case that our built environment is under greater threat today than at any time in a generation.

In the run-up to next year’s local elections in Scotland how many times will the built environment, old and new, be mentioned? I hazard a guess that it won’t figure much in the campaigns of prospective councillors and that health, education, the economy and provision of local services and repeated cuts to funding will dominate. Architecture, planning, development and the historic environment are not generally seen as vote-winners.I think this is short-sighted though. On a recent awards-judging trip to Saltcoats in North Ayrshire to visit the newly refurbished Town Hall, I was struck not just by how rundown and depressed the town was (along with many other towns in the local authority area it is ranked as one of Scotland’s poorest places in the Index of Multiple Deprivation) but by how people there looked older and unhealthier than in more affluent communities. This is hardly surprising but I think it is evidence that a poor quality built environment does not engender self-respect, civic pride and general wellbeing. In fact, as Sir Harry Burns, the ex-Chief Medical Officer for Scotland, has said many times, there is a clear causal link between well-designed, pleasant places and good health. If this is the case, then why do our elected politicians, local and national, not recognise that the built environment is absolutely central to all the priorities listed above as campaign issues, particularly the economy and health?

At some point in the 1970s the word ‘environment’ was shorn of a large part of its meaning to refer only to green issues. In the early days of the Scottish Civic Trust, its newsletter was called ‘Environment Scotland’ as the word encompassed the whole environment, natural and built. At the time there was also an understanding that people wanted to feel proud of their local towns, villages and neighbourhoods and that having a connection to and sense of ownership of place led directly to civic pride and collective responsibility.

There are some 130 groups affiliated to the Scottish Civic Trust. Some are called civic trusts, others amenity societies, ‘friends of’ or heritage groups. Their aims vary but most share a common purpose: to care for, celebrate and champion their local village, town or city.

Many spend a lot of time commenting on planning applications and are battle-scarred from years of fighting inappropriate developments or loss and neglect of heritage assets. Most members of these societies tend to be older and many are retired. They offer lifetimes of experience and come from a wide range of backgrounds. They are, perhaps, not as representative of their larger communities as they would like to be. Almost all struggle with the same issues: ageing membership, lack of voice, recruitment of new, younger members and a feeling of swimming against the tide. With limited success and much frustration they make a stand against waves of inappropriate and ill-conceived development and gradual piecemeal erosion of what makes certain places special.

What drives them on is civic pride in their area, responsibility for its upkeep and future and a determination to stand up for it when it is under threat. Their sense of civic duty harks back to an earlier time, the 1960s and 70s when civic society was at its most active. Then, in response to the widespread destruction of much of the country’s historic fabric, delivered with fervour by modernist zealots from the architectural and planning professions, the Scottish Civic Trust was founded, followed by scores of civic and amenity societies across the country.

In a time when people lived in neighbourhoods for much longer than today’s transient populations, there was a greater connectivity to one’s environment. This cohesion, along with a campaigning spirit, imbued groups to challenge decisions made by planning authorities and city and town leaders and helped to make the conservation movement grow.

The civic movement is still very much alive and kicking today but it faces threats that I believe are more serious and worrying than we have seen for a generation. What are they?

- A lack of leadership at local authority level in most cases to protect and enhance the local built environment. A full audit of all Scotland’s conservation areas needs to be carried out. The loss of influence at the top table by planners and architects and the shortage of design and conservation skills in planning departments. Also, many elected representatives are making decisions on matters related to design, planning and development for which they do not have the required knowledge or expertise.

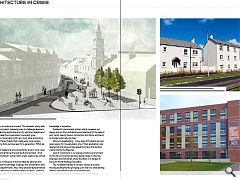

- Scotland’s procurement system which squeezes out design and joy from architecture and planning for the sake of cost, which heavily favours contractors and forces architects to charge historically low fees.

- Volume housebuilding – many areas of Scotland are now open season for housebuilders who, if their applications are rejected at local level, simply appeal and have the decision overturned by the Reporter.

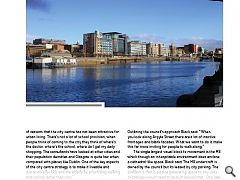

- Lack of investment in our precious historic environment and brutal commercial decisions being made in cities like Aberdeen and Edinburgh where the latter is in danger of losing its World Heritage Site status.

- The incredible number of, at best, mediocre student housing developments springing up all over our cities adding nothing imaginative to the visual streetscape.

- Local authorities are being starved of cash and are compelled to sell off assets and prioritise health and education over architecture and planning as if the issues were not intricately connected.

However, as long as we continue to have a developer-led planning system and where the mantra of economic regeneration is the main driver rather than design and community-led solutions I fear that decisions being made today in haste will have repercussions for generations to come.

|

|

Read next: River Phoenix: Ayr Masterplan

Read previous: Sigurd Lewerentz: Personality Cult

Back to January 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.